Featured Faculty

Thomas G. Ayers Chair in Energy Resource Management; Professor of Management and Organizations

Yevgenia Nayberg

For leaders who care about improving social outcomes, design thinking has tremendous appeal. Design thinking, which combines customer insight, technical expertise, and rapid prototyping, offers quick solutions that are potentially replicable.

But design thinking is not the only pathway to social innovation. According to Klaus Weber, an associate professor of management and organizations at the Kellogg School, the design approach—for all its merits—has overshadowed another important vehicle for social change: community development.

“It’s not as sexy,” Weber says, but there is something uniquely effective about engaging local communities. “Community development can be slow and difficult to scale, but the solutions are usually more durable when they come right out of communities themselves.”

Community development and design thinking are by no means mutually exclusive, though different leaders tend to prioritize one approach over another. Both seek sustainable solutions to seemingly intractable problems such as public housing, healthcare access, safety, or education.

But while design thinking stresses efficiency and scalability, community development places more emphasis on finding solutions that are specifically tailored to the community itself—even if that means slower progress. “There is so much tacit knowledge and value within communities,” Weber says. “Outsiders have to appreciate that before they can help make meaningful change.”

Rather than listing social problems and then coming up with solutions, community developers focus on unique strengths and hidden value. They try to build from what’s already there.

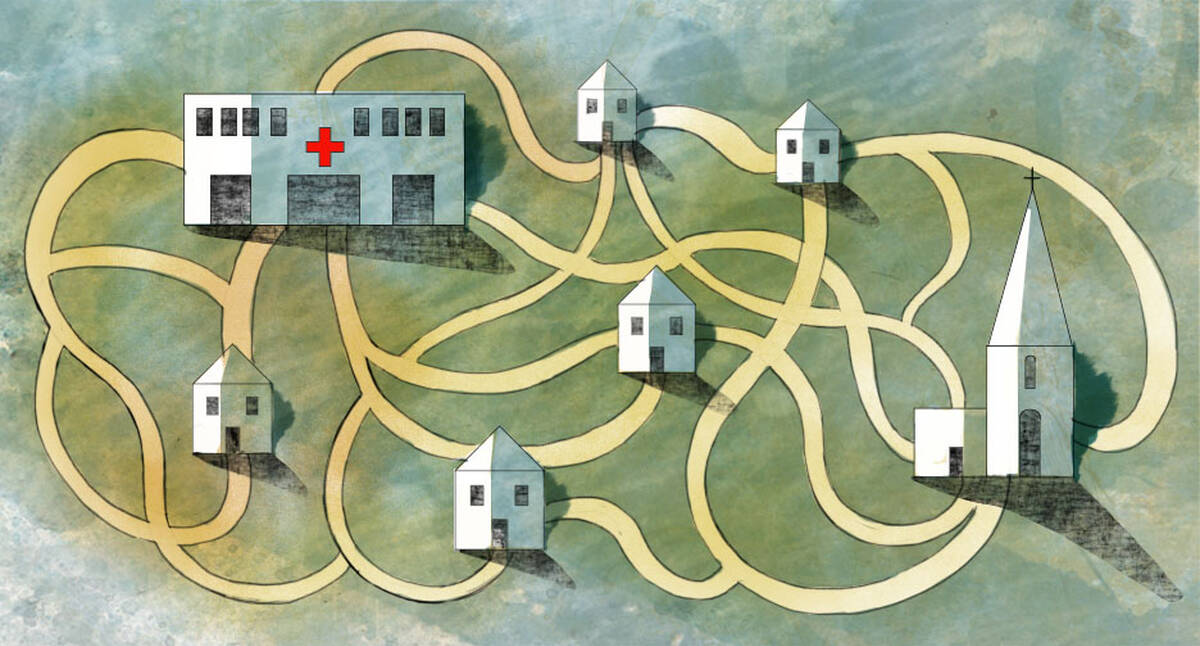

A community developer might first approach a problem by engaging in “asset mapping,” or identifying the strengths and resources that already exist within a community. Assets might include the skills of local people, the networking potential of local institutions, and any underutilized infrastructure—even the local culture.

“Rather than listing social problems and then coming up with solutions, community developers focus on unique strengths and hidden value,” Weber says. “They try to build from what’s already there.”

Consider, for example, the forestry expertise of Solomon Islanders, which was instrumental to building better housing for villages, or the “savings culture” indigenous to the Ethiopian highlands, an asset that makes it possible to offer more advanced financial services. In both cases, tapping into local assets—ones that may not have been immediately visible from the outside—made a significant difference in the durability of the outcomes.

Despite their potential for quick results, design solutions sometimes ignore the “social” aspect of social innovation. “It’s one thing to innovate within a business; it’s another thing to innovate within a community or culture,” Weber says. “For example, how can you prototype with communities? They don’t want to be your guinea pig. They don’t want to ‘fail to learn.’ They just need it to work.”

And sometimes even that is not enough. Designing solutions that work well in the short term does not always address underlying issues of community pride and social justice.

“It’s about more than ‘service delivery,’” says Deborah Puntenney, an associate professor in the School of Education and Social Policy at Northwestern University and researcher at the Asset-Based Community Development Institute. “Community development works because it is really about empowerment.”

In Rochester, New York, where Puntenney has been using asset-based community development to improve local health outcomes, residents are encouraged to make decisions on behalf of the community through their own neighborhood-based organizations. Outside groups can certainly help, but only if they work as partners—humble ones. “No matter what your credentials are, there are certain things you simply can’t know about a community unless you’ve lived in it,” she says. “So the first step is to lose your hubris and become a better listener.”

While private-sector ingenuity can sometimes address social problems more efficiently than governments—this, after all, is the basic premise of “social innovation”—in reality, the public and private sectors are not always starkly divided: there are plenty of hybrid initiatives.

“We should welcome any approach that genuinely improves social outcomes,” Weber says. “Some people have a passion for design, others for public policy. The principles of community development are a good foundation for either approach, and the tools apply to either sector.”

Whatever the pathway to social innovation, the key is to combine ingenuity with a willingness to truly engage. “It’s something we’re still improving,” Weber says. “But it’s clear that the best social enterprises will have this at their core.”