Marketing Social Impact Jun 6, 2017

To Improve Fundraising, Give Donors a Local Connection

Research offers concrete strategies for appealing to donors who want to make an impact.

Lisa Röper

We intuitively understand that a ball hurled directly at our face hurts more if thrown from a few feet away than from the other side of the baseball diamond. The closer the target, the bigger the impact.

But do people apply similar thinking to decisions about charitable donations? Do we believe our gifts will have more impact if the recipients are nearby? And does that perception make us more likely to give to causes close to home?

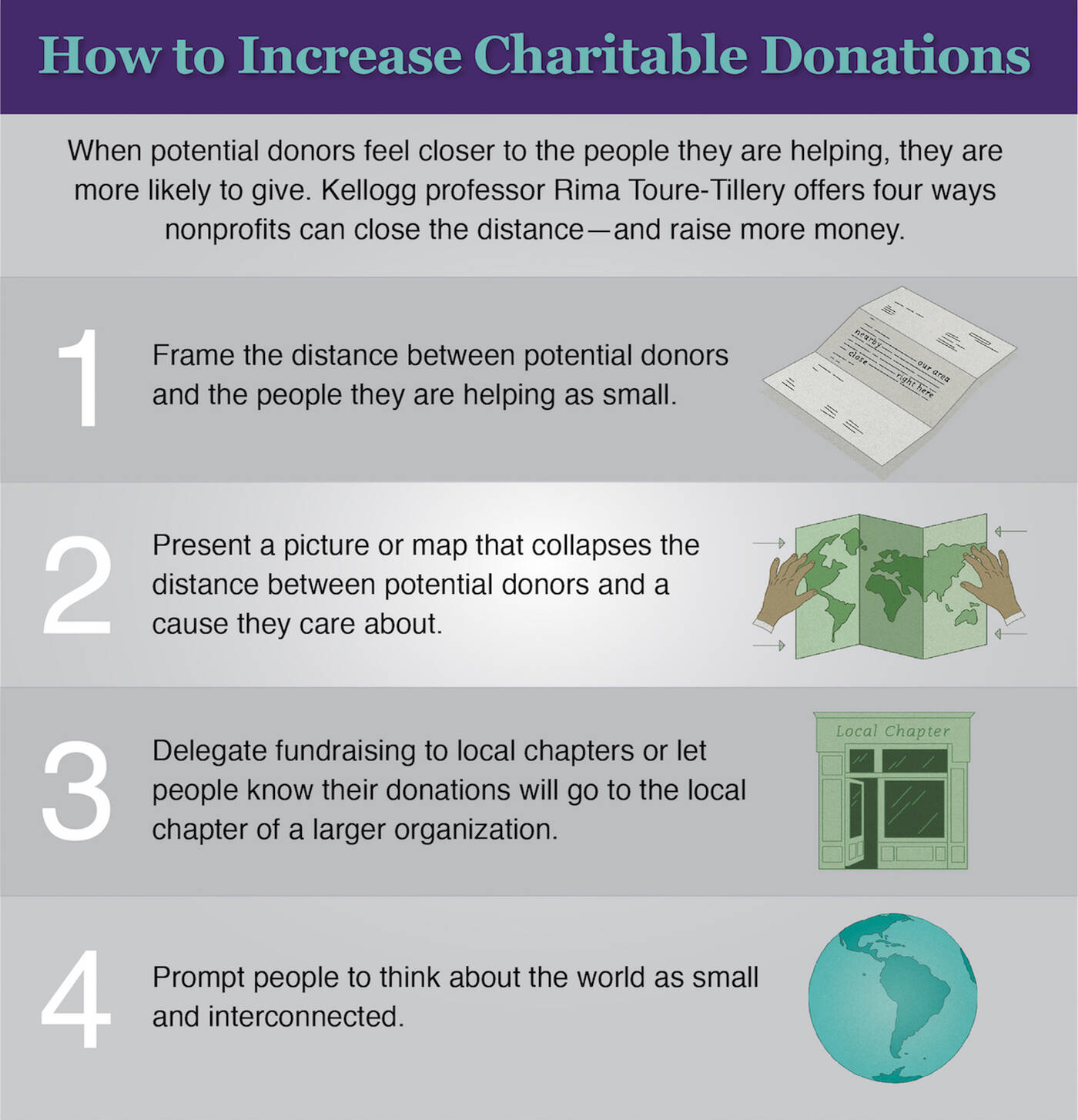

These are the questions Rima Touré-Tillery, an assistant professor of marketing at Kellogg, and a colleague investigated in recent research. But instead of asking if people would donate more money to a cause in, say, the United States than one in Africa, the researchers employed psychological tricks to make a single location—such as Haiti—seem closer or farther away.

Of course, Haiti cannot really shift locations. Yet the team found that when potential donors simply perceived recipients to be nearby, it made those people believe their donations would exert more influence. And study participants who were encouraged to think this way were more likely to say they would give money.

Charitable organizations could use these results to help raise money for international causes by making them feel closer.

“Purely framing something as far or near makes a difference,” Touré-Tillery says.

The Power of Metaphor

People typically donate to causes for two main reasons, says Touré-Tillery. “People donate because they want to help and because they want to feel good about themselves.”

Touré-Tillery and Ayelet Fishbach at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business were interested in the former motivation: the desire to have an impact. Previous research has shown that people are more likely to give if an employer matches their donation, which doubles its impact. But what about an increase in impact that exist only in the donor’s mind?

Metaphorical thinking might play a role in donation decisions, the researchers thought. Our ideas about the physical world—that throwing an object has a bigger impact on nearby targets—could color perceptions of a donation’s impact. After all, “a lot of the way we think about things is metaphorical,” Touré-Tillery says. Consider how we often imagine powerful people as being “higher up” than weaker ones, or how we frequently depict time proceeding along a horizontal line.

Lisa Röper and Karen Freese

A Physics Lesson

To explore this idea, the researchers performed an online experiment with nearly 200 people in the United States using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform. One group of participants saw pictures of a stick figure throwing a round object horizontally at both a nearby and faraway figure. This was intended to remind participants of the idea that physical objects have a greater impact on closer targets. A second group saw pictures contradicting that idea: an object being dropped vertically on either a nearby target or a faraway one. In this situation, the impact on the closer target would be weaker because gravity has less time to exert itself.

Then participants were asked how hard they expected the object to hit each target and why.

Next, the team presented both groups with passages asking for donations to help children in Guatemala and Honduras. Some people read a description implying that the recipients were nearby, using language such as “right near you” and “short distance,” while others read a description that suggested the opposite, with phrases such as “all the way from” and “long distance.” The participants then estimated how much they expected a $10 donation to help.

In the group that saw the horizontal throwing, people who had read the “nearby” description rated the donation impact at 4.58 out of 9 while those who read the “faraway” description rated it lower, at 4.30. But in the group that saw the vertical dropping, there wasn’t much difference between the nearby and faraway conditions. Disrupting the metaphor of closeness equaling impact appeared to cancel out people’s tendency to believe their donations would matter more if sent nearby, Touré-Tillery says.

Near and Far

But people do not generally see stick figures before pressing the “donate now” button.

So the team conducted a couple of real-world studies. First, they obtained anonymized data on 172,441 alumni from a U.S. university. They analyzed the relationship between distance to the university and donations to the school in 2014, controlling for factors such as graduation year, degree type, and typical income in the person’s area. As expected, alumni who lived closer to the school tended to donate more money.

Though promising, that study did not necessarily show that the gifts were driven by perceptions of higher impact. Nearby alumni might have given more because they heard about the university more frequently or knew current students or employees.

“Any way you can frame the recipient as being close to the donor can only help.”

So Touré-Tillery and Fishbach designed a more rigorous experiment. With administrators at a different U.S. university, the researchers sent letters to 19,731 alumni living in the country. One version used language suggesting the school was nearby, while another version implied it was far away. Only about 90 people donated in response—a not unexpectedly low rate given that many letter recipients had never donated to the university before. Among the letter recipients, perceived distance appears to have made a difference: 0.57% of recipients who got the “nearby” letter gave money, compared to 0.33% of those who got the “faraway” letter.

A Shrinking World

The researchers then explored other ways to make places seem closer. In one experiment, 160 online participants were offered a chance at a $20 raffle prize. One group read and retyped a paragraph about globalization that described how new technology had made the world shrink and noted that “No country, city, town or village is too far away.” Another group copied a paragraph that emphasized the opposite idea: a description of long-distance flights that traverse “a great circle along the diameter of the Earth.” Participants were then asked if they would donate $10 of their potential raffle winnings to an Ivory Coast charity.

About half of the people who read about globalization agreed to donate, while only about one-third of those who read about long flights did. A similar study confirmed that participants who retyped the globalization paragraph rated the Ivory Coast as being closer than did people who copied the flights passage.

“Even the most objectively faraway places can be perceived as not being that far away,” Touré-Tillery says.

Underlying Motives

In a final study, the researchers found that there is at least one situation in which perceived difference has little effect on willingness to give: when people are focused on how giving money benefits themselves, rather than how it benefits the recipients.

In an online experiment, the team showed appeals for donations that emphasized either helping others (“make a difference”) or displaying generous behavior (“show support for Haiti”). In the group that was asked to “show support,” willingness to give was similar regardless of whether Haiti was described as near or far.

“When people are in that mindset, distance is not going to make a difference,” Touré-Tillery says.

Overall, however, the study suggests that altering perceptions of distance can affect people’s decisions to give—even if the actual proximity has not changed. Organizations might consider crafting their appeals to make recipients seem closer to home. For example, an international charity could designate a local branch as the point of contact for donations. [See inforgraphic above for more ideas.]

“Any way you can frame the recipient as being close to the donor can only help,” Touré-Tillery says.