Leadership Mar 7, 2016

Cultivating Trust Is Critical—and Surprisingly Complex

Don’t rely on intuition for something this important.

This audio is powered by Spokn.

Yevgenia Nayberg

Trust is the basis for every business exchange and all consumer behavior. But as important as it is for leaders, organizations, and brands, the fundamental concept is surprisingly hard to pin down.

“Whenever any two people talk about trust, they may think they’re talking about the same thing when they actually aren’t,” says Kent Grayson, an associate professor of marketing at the Kellogg School and faculty coordinator of The Trust Project at Northwestern University, an initiative designed to advance the study and management of trust in business and society. Yet, people are not always aware of this ambiguity—or of the importance of trying to resolve it. “We tend to build trust by intuition—in everyday life and in the business world. That usually works OK, especially for experienced business professionals. But even seasoned managers who build trust only by intuition may be missing opportunities to leverage trust more effectively—with employees, customers, and business partners.”

The Trust Project aims to create a unique body of knowledge by connecting scholars and executives from diverse backgrounds to share ideas, research, and actionable insights in a series of videos for research and management. Learn more about the project and its development in conjunction with the Kellogg Markets and Customers Initiative.

Grayson argues that taking a systematic approach to the process of building trust has distinct business advantages. Trust, after all, is a powerful force: it can win customers and deepen important relationships. “If you’re a business person, you can’t afford to rely on intuition alone for how you manage trust with your stakeholders.”

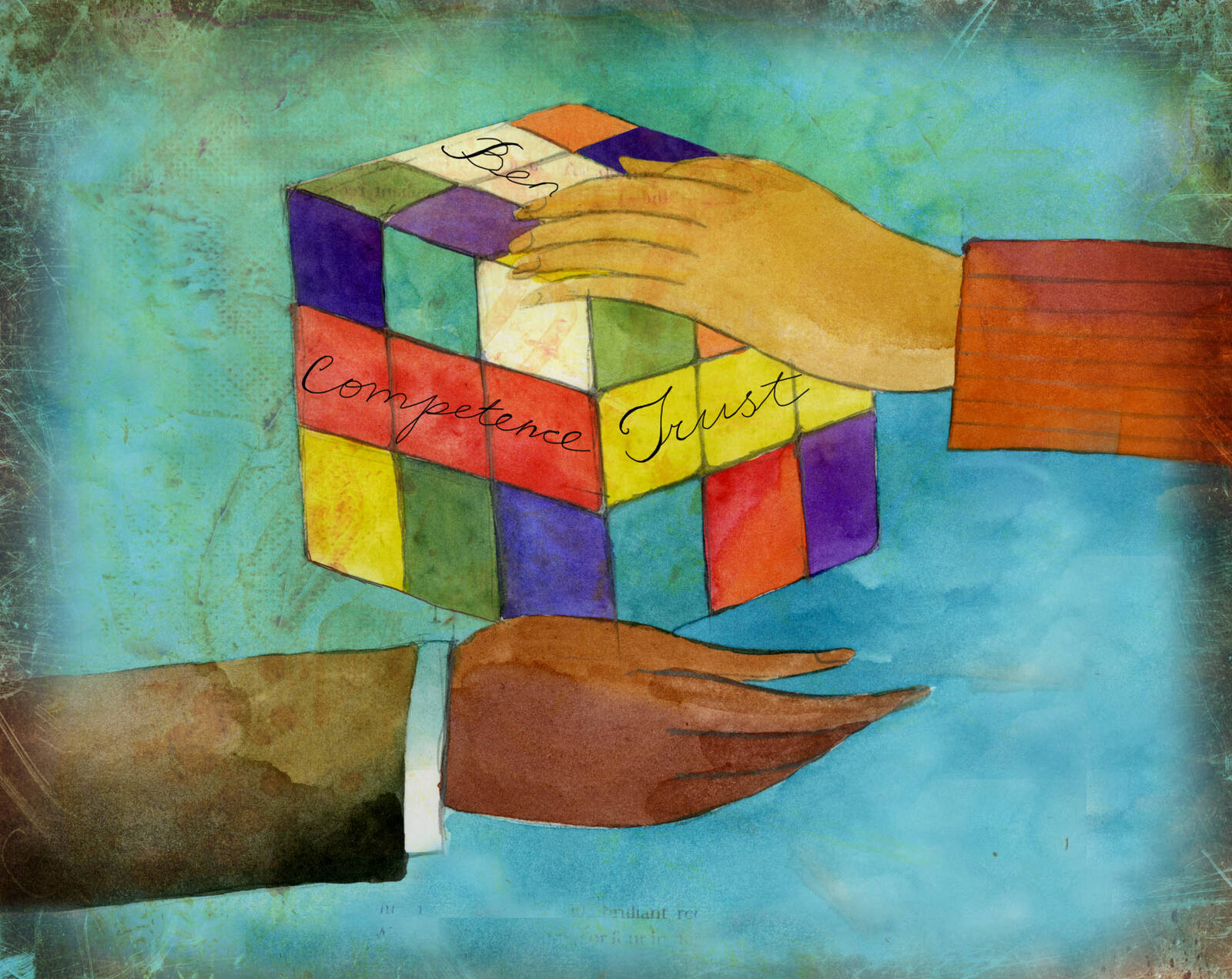

The Three Dimensions of Trust

A long history of research demonstrates that trust can be broken down into three components: competence, honesty, and benevolence. To trust someone’s competence is simply to believe that the person or entity you deal with has the ability to do the job—to provide you with Internet service, for example. Honesty—or integrity—refers to your sense that your Internet service provider keeps its promises and is not telling lies about your connection speed or hiding fees. Benevolence is the belief that your Internet provider has your best interests at heart and cares about you as a customer.

In business and in life, of course, we are not always aware that trust is being built (or undermined) based on these three dimensions. And this can lead to errors in how we manage trust with others.

“Even seasoned managers who build trust only by intuition may be missing opportunities to leverage trust more effectively.”

For example, research suggests that managers naturally tend to emphasize their competence while downplaying benevolence—an approach that can often undermine trust more than enhance it. In practice, this tendency is common to leaders no matter what field they are in. Consider the story of the local Afghan governor whose driver got lost on the way to a meeting with U.S. officials. Fearing ridicule for not knowing his own province, the governor decided to skip the meeting rather than arrive late. Without realizing it, he sacrificed integrity rather than have his competence questioned.

Research on trust is beginning to reveal greater nuance in terms of how these dimensions relate to each other. Honesty and benevolence, for example, have been found to be highly correlated. Both, it seems, contribute to a general sense of “warmth.” And warmth, it turns out, is something we are hardwired to judge very quickly—within 100 milliseconds.

Scoring Better across the Board

Leaders, companies, and brands have a lot to gain from developing a systematic understanding of the components of trust and determining how they can score better on each. “One thing we’ve found is that you can build trust on one of these three dimensions and still be weak on others. A leader may not realize that he or she is trusted in one dimension but not across all dimensions,” Grayson says. “The same holds true for companies and brands.”

The good news is that there are actions you can take to build trust in areas where it may be in decline. Consider the case of Cooperative Bank, a U.K.-based financial institution that worked with Grayson and coauthor Devon Johnson on trust-management issues. In preparation for trying to gain share in its financial advisory business, the firm measured how it stacked up relative to its competitors in terms of trust. When senior managers discovered that customer perceptions of benevolence could improve, the bank directed resources and energy toward improvements on this dimension. The result was a huge increase in customer loyalty and sales volumes. “It might be worth considering: In which dimension are we weakest?” Grayson says.

Acknowledging the nuances of trust can also make crisis-management more actionable. When a company can pinpoint the areas of trust that have been most affected, it can take steps to address those areas.

Take the example of the senior living facility that was in financial and management turmoil. A new management team came on board facing a serious financial crisis. The challenge for this team was to communicate the details of the facility’s financial state without eroding trust and causing residents to flee. After mapping out all the stakeholders, management decided their first priority should be transparent communication with the residents and their family members. By demonstrating integrity, the new CEO was able to build trust, which resulted in resident retention.

Given how great of an impact trust can have on any exchange relationship, leaders and brands should pay closer attention to how they are building it. “To understand trust is to understand the conditions that facilitate economic exchange,” Grayson says. “That’s why we think it makes sense to look closely at how it works.”