Policy May 22, 2023

What’s at Stake in the Debt-Ceiling Standoff?

Defaulting would be an unmitigated disaster, quickly felt by ordinary Americans.

Michael Meier

Here we are again: at the brink of the debt ceiling and wondering whether this is the time we careen into default.

Kellogg Insight recently sat down with David Besanko, Kellogg’s IBM Professor of Regulation and Competitive Practices, to better understand the stakes. He explains that while efforts to reign in debt have merit, defaulting on our debts would be an unmitigated disaster, from which few Americans would emerge unscathed.

*

Kellogg INSIGHT: How big is the U.S.’s debt? How much does having a lot of debt matter?

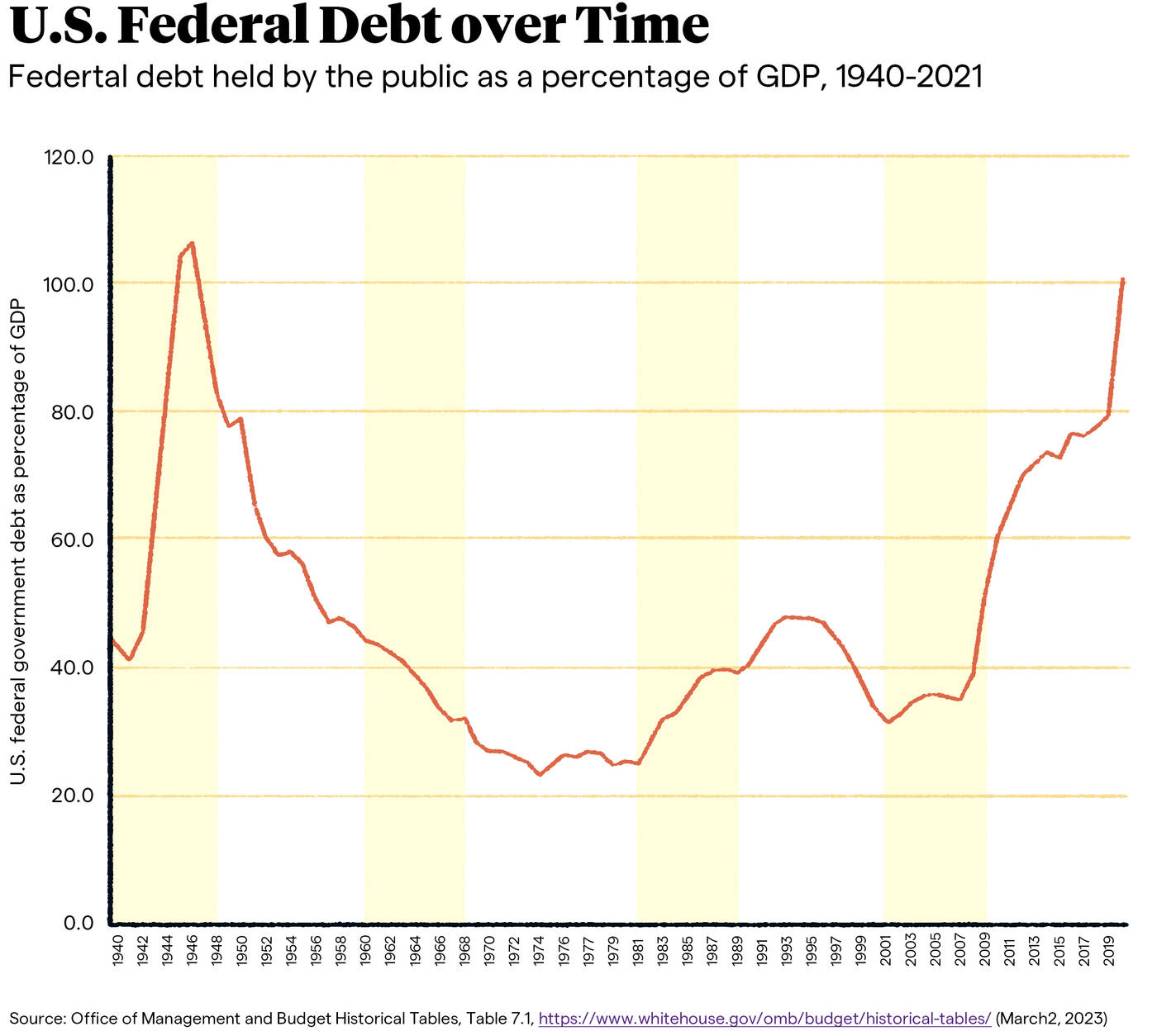

David BESANKO: Federal debt as a percentage of GDP has increased dramatically, particularly since the Great Recession. The debt held by the public (which excludes federal debt held by government accounts, such as the Social Security Trust Fund) is now about 100 percent of GDP.

It’s not a big deal in the sense that it is going to lead to any sort of imminent emergency, and it’s also not necessarily the case that it will encumber future generations with hardship.

But high levels of national debt matter for three reasons. First, it can make interest rates higher than would otherwise prevail. That may reduce private investment and serve as a headwind for economic growth. Second, it makes it less likely that the U.S. federal government will make long-term investments in things that are good for economic growth, such as investments in research and development, science, infrastructure, and programs that benefit children. Finally, it makes it less likely that the county would be able to do all that it needs to do from a fiscal perspective to fight a future recession.

INSIGHT: What is the debt ceiling? Where did the concept originate?

BESANKO: The executive branch needs the approval of Congress to borrow money. Congress was originally required to approve every individual debt issuance. Because the federal government grew significantly during the first World War, it had to go to the market to borrow money with increasing frequency. It became cumbersome for Congress to approve every individual debt issue, so in 1919 Congress established the debt ceiling: so long as the federal government stayed under that limit, the executive branch didn’t need to keep asking Congress for permission to issue new debt. In a way, then, the debt ceiling began to make it easier to borrow money.

But, of course, this means that, during periods where the national debt has grown (as was the case in the 1980s and early 1990, as well as in the years since 2007), we have bumped up against debt limits that previous Congresses have established. Consequently, Congress often needs to vote to raise the debt ceiling. In the 84 years since Congress established the limit in the form it exists today, it has voted to raise the debt ceiling 98 times.

One could argue that the debt ceiling is unnecessary, though, because Congress can already control the lever of funding through the appropriation process. If Congress does not want to appropriate as much money for various programs, it can choose to do that. If it wants to pay for spending through higher tax revenue rather than borrowing, it can choose to do that, too.

This effectively makes the debt ceiling a constraint on the ability of the government to borrow money for programs that have already been established and for which money has already been appropriated, as well as for programs like Social Security and Medicare, where Congress has already written the rules as to what the benefit levels are.

INSIGHT: How big of a deal would default be?

BESANKO: There are several reasons why it would be a big deal. Number one is that the government outflows would fall. Given that the deficit is about 20–25 percent of total government spending, outflows would fall by that amount. That’s an abrupt shift toward austerity unlike anything we really have seen before. The macroeconomic effect would be significant even if it persisted over just a few months.

“We don’t want to see what happens. We don’t.”

—

David Besanko

The second effect relates to the financial system. If the federal government defaulted, the ratings agency would take steps to downgrade us, and the “risklessness” of government Treasury bills, notes, and bonds would be called into question. Treasury securities are an important form of collateral, so what happens if they are now perceived to be risky? Well then you might have margin calls, where financial institutions start calling in loans that have been secured by this now–higher risk and less-valuable form of collateral. And then you have borrowers who are scrambling around to meet these margin calls, and they have to sell securities to raise the cash that they need to pay their loans. This is the kind of dynamic that could put the entire financial system at risk.

The third effect, which I think is a little overlooked in the discussion right now, is what happens to real people. The federal government’s bills won’t be paid, meaning a vendor for the Department of Defense can’t meet payroll and may have to lay off people, or a physician’s office that doesn’t receive Medicare reimbursements may shut down, or a family doesn’t get their tax refund and their home purchase falls through. And, of course, if elderly people do not get their Social Security checks on time, that could mean not meeting rent. The consequences for Americans living their everyday lives are really significant.

INSIGHT: Okay, so how is this going to play out? Are Republicans really prepared to default if they can’t reach an agreement with the Biden administration? Is there anything the Biden administration can do to unilaterally lift the limit?

BESANKO: Republicans in the House of Representatives have said they will not raise the debt ceiling without spending cuts. As for whether this means they are prepared to default, I’m not sure. There is a view among some Republican lawmakers that, because interest is only about 8.4 percent of federal outlays, bondholders can still be paid, meaning no default. But this is absurd. It’s not clear the government’s IT system can handle this kind of prioritization, there could still be economic consequences, and it’s just not an experiment we want to run.

In terms of preventing the worst consequences of a default, the Biden administration has some responses, but none of them is a silver bullet.

For example, if the administration invokes the Fourteenth Amendment and keeps issuing Treasury securities anyway, that will be challenged in court, meaning anyone buying these Treasury securities is going to be faced with the possibility that they could be rendered invalid, meaning there would be a risk premium. They would sell at a very high interest rate. That raises interest costs in the medium and long term, but at the same time it would be very unsettling in the financial markets. The same kind of rattling that would occur if there was an actual default would occur here. Maybe not as extreme, but it would still rattle financial markets around the world.

The same for goes for the platinum coin. In fact, I’m of the view that’s even more of a nonstarter. Congress passed that law in 1996 enabling the creation of commemorative coins: this legislative history would be used by the courts to invalidate any attempt to use a trillion-dollar platinum coin to circumvent the debt limit.

There are other approaches, such as issuing the premium bonds, that are more interesting. Premium bonds pay at above-market interest rates, meaning people might be willing to pay an amount greater than their face value. Since the face value of an outstanding Treasury security is what counts against the debt limit, a premium bond with a $1,000 face value that sells for, say, $1,700 would enable the federal government to repay the principal on $1,000 of existing debt, leaving $700 of extra money that can be put toward government expenses. Because there would be no net additional principal that would count against the debt limit, premium bonds are a way for the federal government to continue to borrow within the existing debt limit. In effect, premium bonds are a way to circumvent debt limits. Local governments and school districts sometimes use premium bonds to do just this.

But the ship has sailed here. This is something the administration could have done late last fall after it became clear the GOP would have control of the House of Representatives. They could have tested the waters, issued a series of premium bonds in the public markets to see what happened. But they didn’t, and I think it is now too late.

INSIGHT: Any final thoughts?

BESANKO: I’ll say it again: The results of breaching the debt limit are perilous. If we get to the point where the U.S. Treasury no longer has enough cash to pay all the bills on a day- to-day basis, we risk inflicting enormous harm on millions of Americans. We don’t want to see what happens. We don’t.

This is exactly why the Biden administration has decided to negotiate after saying they would not. If they do negotiate a deal—which I think they will—this is a good outcome for the administration, even though it will be widely seen as a political loss. Spending will be cut, which would probably have happened anyway as part of a budget deal later in the year, and cutting spending is directionally what you want to do when the economy is still running a bit hot, as it is now. Though the administration would have preferred a more balanced approach of spending cuts paired with tax increases—a view I share—a budget deal along the lines of what’s likely to emerge will help keep inflation moving downward, without reducing too much the likelihood for a “soft landing.” This is a good thing for the administration as it positions itself for 2024.

Jessica Love is editor in chief of Kellogg Insight.