Featured Faculty

J. Jay Gerber Professor of Dispute Resolution & Organizations; Professor of Management & Organizations; Director of Kellogg Team and Group Research Center; Professor of Psychology, Weinberg College of Arts & Sciences (Courtesy)

This audio is powered by Spokn.

Michael Meier

The Friday team meeting you lead has gone off the rails. The same way it did last Friday, and the Friday before. In fact, it’s hard to remember the last time you had a truly productive meeting.

Individually, none of these tangents or bungled opportunities would be a big deal. But cumulatively?

“It’s not in our everyday awareness,” says Leigh Thompson, a professor of management and organizations at the Kellogg School. “But it turns out these small but numerous time sinks are piling up to the equivalent of a massive landfill.”

Thompson and her colleague Tanya Menon of the Ohio State University distinguish between two types of spending. “Type I” is spending in its typical sense—the kind that prominently appears on financial statements. In contrast, “type II” spending—squandered work time—goes unrecorded. But it is no less important. To start to get a sense of how much type II spending occurs, Menon and Thompson asked 87 senior executives to estimate what wasted time had cost their companies. The average answer: nearly $15.5 million.

As it turns out, most type II spending originates from dysfunctional workplace dynamics—more commonly known as “people problems.” In their book, Stop Spending, Start Managing, Thompson and Menon describe some of the thorniest people problems that leaders handle, or rather mishandle, every day.

Here are three such problems—as well as what managers can do to stop reinventing the wheel, start encouraging productive conflicts, and save a lot of time in the process.

Thompson describes a familiar blind spot from which many high-performing teams suffer: they become so used to “winning,” either individually or as a group—being right, being the first, being the best—that they become unwilling to seek valuable information from one another, since doing so would be a tacit admission of imperfection or weakness.

“The problem is that we cannot all be winners,” Thompson says. “We see so much status competition going on in organizations that it’s difficult for us to learn from one another.”

In a study conducted with Tanya Menon and Hoon-seok-Choi, who completed a post-doc at Kellogg and now is on faculty at Korea’s Sungkyukwan University, Thompson found that when given a choice between spending a hypothetical R&D budget on the ideas of an internal rival or those of an outside competitor, managers were willing to spend 42 percent more on the outside competitor’s ideas. “This is why consultants get hired,” Thompson says. “We bring in outside people to tell us something that we already know,” because it paradoxically means all the wannabe “winners” in the team can avoid losing face.

While Thompson has nothing against consultants, she urges taking the shortest path to valuable insights: quite often, a rival’s. The trick for opening up that path, she says, is simple: “List one or two things you’re particularly proud of.”

Perhaps you just published a book or a well-received case study; perhaps you had an above-average performance review last quarter. “Now all of a sudden,” she says, “when I hear about the accomplishments or ideas of a colleague, I am more receptive to it—because I have just reminded myself that I am not chopped liver.”

Most managers are put in a double bind, says Thompson, in terms of the directives they pass along to their teams. “On the one hand, we’re saying, ‘Get to the top’; on the other hand, we are saying, ‘Be a good team player.’ So people come into meetings, and they don’t know what’s expected: Should I have on my ‘I’m a team player’ hat, or my ‘I’m a lone genius’ hat?”

The rub, of course, is that both of these hats are terrific—but only in certain situations. And since most people do not seek out disruptive conflict, the teamwork hat in particular can become a liability. Thompson cites an episode at Rhode Island Hospital where, in 2007, three different brain surgeons cut into the wrong place on a patient’s head. In each case, the surgeons’ support staff were being such good team players that they either failed to bring the error to the surgeons’ attention or did not do so aggressively enough to compel the surgeons to admit their mistake.

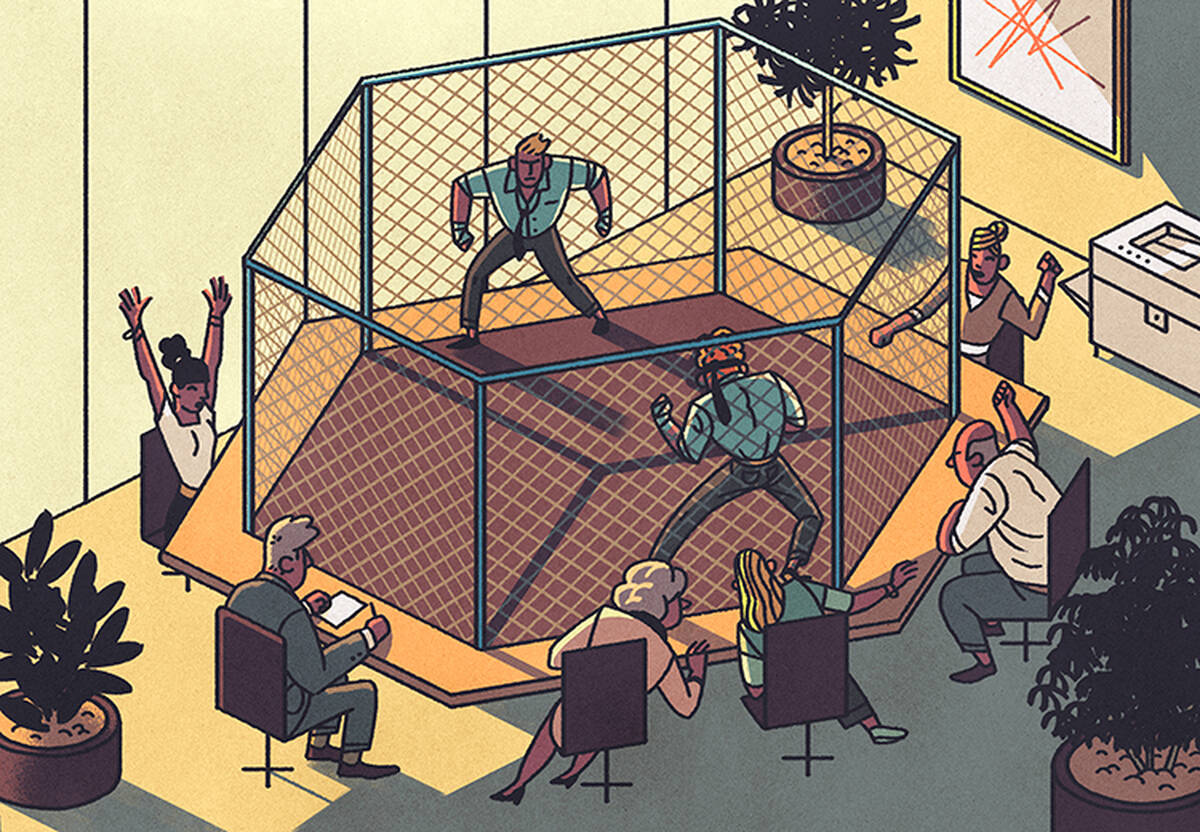

“When we’re in the boxing ring, I am not trying to be nice to you. I am trying to point out flaws in your approach. But knowing that it’s a boxing ring means that we both know I am not attacking you, I am being hard on the problem.”

Few business decisions have stakes that dramatic. But ambiguous expectations from managers, combined with a default desire for teamwork, can still paralyze necessary communication. “It’s like being at a dinner party, and I have no idea what fork to pick up, so I am not going to even eat,” Thompson says.

One tactic for avoiding this trap is to remove ambiguity. Thompson and Menon recommend establishing “boxing rings”—circumstances in which everyone knows the ground rules for conversational combat and also knows that they are not personal.

“When we’re in the boxing ring, I am not trying to be nice to you. I am trying to point out flaws in your approach,” Thompson says. “But knowing that it’s a boxing ring means that we both know I am not attacking you, I am being hard on the problem.” For consensus-building, “campfires” take the converse approach.

Thompson says that companies can implement this tactic literally by designating a certain conference room as the ring and another as the campfire, rather than just treating every windowless beige room identically (and ambiguously).

“We should take much more accounting of how the physical environment, and all the cues therein, influence people’s behavior,” she explains. “It’s a way to globally lower the stakes for initiating these productive conflicts.”

It may seem obvious that when you’re faced with a difficult problem, you want to bring in the best experts to solve it.

Only, sometimes, you don’t. Sometimes expertise can get in the way.

Consider this example: In 2008, a team of university biochemists was frustrated after failing to make headway on a series of complex protein-folding problems. Instead of seeking out more experts, they decided to ask thousands of amateur online gamers for help. The scientists’ ingenious approach was to present the protein simulations as a puzzle game called Foldit.

And their gambit paid off: “The gamers, many of whom had never taken a course in biology, solved the problem within two weeks,” Thompson says, “because they weren’t blinded by the assumptions that the biologists were using.”

Thompson is not arguing that managers embrace total indifference to expertise. But in situations where know-how has come up short, she recommends abstracting away from the problem’s details in favor of exploring its deeper structure. That is how the biologists were able to leverage the pattern-matching capabilities of nonexperts—and it is how expert decision-makers can bypass their own idiosyncratic biases and blind spots.

Take, for example, the thorny question of which doctoral students are likeliest to succeed in their programs. Back in the 1970s, Robyn Dawes, a University of Oregon psychologist, analyzed the performance of past PhD students in the hopes of modeling a simple, effective procedure for selecting new PhD candidates. Dawes’s model drew on factors that the admissions committee already believed to be important, like grades, GRE scores, and the quality of the undergraduate institution. But critically, his model offered a more accurate and more consistent way of combining these factors than did the intuitive and idiosyncratic judgments of the expert committee.

“It turns out that a model of a decision-maker is better than the decision-maker itself,” Thompson says. After all, statistical models don’t have longstanding biases about which factors matter most; they also don’t have headaches, or get fatigued.

But you do not always have to fit up a statistical model in order to sidestep the expertise trap, says Thompson. Instead, you can get similar benefits just by inviting someone into your decision-making process who brings different expertise to the team.

“Chances are, that is going to be a person whom you don’t get along with,” Thompson admits. “But if I can put that aside, they might have a completely different lens for viewing my problem.”