Featured Faculty

Walter J. McNerney Professor of Health Industry Management; Professor of Strategy

Michael Meier

The delivery of healthcare in the United States has, over the last several decades, increasingly been consolidated into the hands of large providers.

In this excerpt from Big Med: Megaproviders and the High Cost of Health Care in America, David Dranove, a professor of strategy at the Kellogg School at Northwestern University, and his coauthor, Lawton R. Burns of the Wharton School at University of Pennsylvania, explain why these megaproviders have become “megaproblems.”

In the spring of 2018, Northwestern Medicine opened its new hospital campus in the leafy Chicago suburb of Lake Forest. The $400 million dollar complex is the latest addition to Northwestern Memorial HealthCare’s impressive system.

The sprawling main campus, which sits immediately east of luxury shopping on Chicago’s famed Michigan Avenue, includes the recently constructed $280 million Prentice Women’s Hospital and $600 million Lurie Children’s Hospital. The nearby flagship Northwestern Memorial Hospital has undergone more than $1 billion in expansions and renovations. Northwestern’s four thousand physicians, including fifteen hundred who are employed by the system, practice at more than two hundred facilities throughout Chicagoland, delivering the whole gamut of patient services, from basic primary care to the most technologically advanced diagnostic and surgical procedures. Northwestern also seems to have converted any number of defunct Borders, Office Depots, and Linens and Things into freestanding medical office buildings.

This enormous medical care provider is also a big business. Northwestern is Chicago’s sixteenth largest employer and, with annual revenues of around $5 billion, it brings in as much money as many well-known global businesses, such as Goldman Sachs and Tiffany, and about the same as Fox News, CNN, and MSNBC combined! Northwestern is not even the largest health system in the Chicago metro area. That honor belongs to Advocate Health, whose annual revenues exceed $6 billion. Northshore University Health, the University of Chicago, and Loyola Medicine are not that far behind. As big as they currently are, they continuously plow their revenues into further growth, spreading their tentacles further and further across the Chicago metropolitan area.

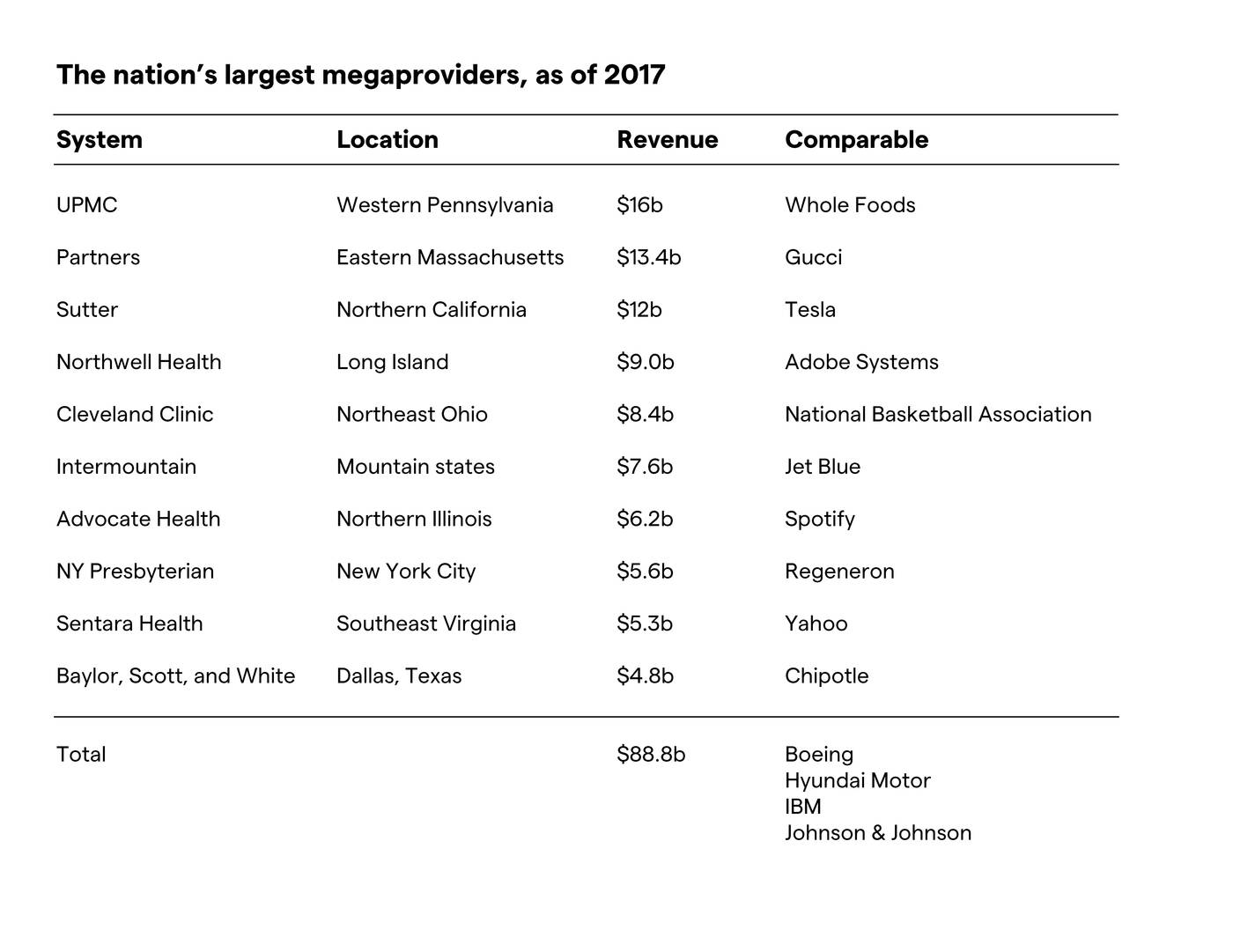

Chicago is far from unique. Nearly every metropolitan area has its own giant health care systems; we call them megaproviders. The table above gives annual revenues for some of the top local megaproviders and identifies national and global companies in other industries that have similar revenues. Baylor, Scott, and White, which dominates the Dallas health care landscape, does as much business as Chipotle worldwide. Northwell, which dominates Long Island, is as big as Adobe Systems. The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, which has a near stranglehold on Pittsburgh and much of the rest of western Pennsylvania, is as big as Whole Foods. These megaproviders are so large because the overall health care industry is enormous. With total US health care spending approaching $4 trillion, equivalent to roughly 18 percent of gross domestic product, even a locally based health care organization can be as big as giants in other industries.

These are just the tip of the iceberg. Other megaproviders include Fairview Health Services (eleven hospitals in the Twin Cities), Emory Healthcare (ten hospitals in the Atlanta metro area), BJC Healthcare (nine hospitals in and around St. Louis) and Jefferson-Einstein (eighteen hospitals in the Philadelphia area). Some systems span several local markets, with dominant positions in some places if not everywhere. Adventist-Providence St. Joseph operates nine hospitals across northern California; ProMedica has thirteen hospitals in Ohio and Michigan; Greenville-Palmetto owns thirteen hospitals across South Carolina; Wellmount-Mountain States operates twenty-one hospitals in Tennessee and Virginia; and Atrium Health runs forty-eight Hospitals in the Carolinas and Georgia. All megaprovider systems own several hospitals, employ or ally with thousands of physicians, and have countless freestanding outpatient facilities and long-term care beds. A few offer their own health insurance products.

With mega-sized revenues comes mega-sized executive compensation. In 2017, at least fifty executives at nonprofit systems earned more than $4 million. At the top end, seven executives earned more than $8 million, with Inova’s CEO bringing home $14 million, topped only by the $16 million that Kaiser paid to its CEO. These figures may seem excessive, but they are in line with how other big businesses pay their executives. If we equate size with success, then health system CEOs have earned every penny. If we instead demand that our CEOs contain costs, then some would be lucky to make the minimum wage.

As health spending spirals out of control, putting health care beyond the reach of many Americans and eating into the savings of many more, it is no wonder that a large majority of Americans believe that the US health care system is broken. According to a recent Leavitt survey, 70 percent of respondents believe that the system requires fundamental changes or even a complete rebuild. Most Americans blame insurers, drug makers, and the government for the current predicament, and it is no surprise that drug makers compete with health insurers for most frequently being described as “rapacious.” Very few Americans—no more than 5 percent in the Leavitt survey—blame hospitals or doctors. Likewise, politicians are quick to blame insurers and drug makers—some prominent Democrats refuse to accept contributions from them—but they rarely blame hospitals and physicians, and eagerly accept their big dollar contributions. The blame is misplaced. Neither insurers nor the government order tests, write prescriptions, or perform surgeries. While many drugs are expensive to the point of seeming exorbitant, prescription drug spending accounts for less than 11 percent of total health spending. You could eliminate all administrative costs, wipe out insurance and drug industry profits, and slash their executives’ salaries, and health care would still be incredibly expensive.

Big Med: Megaproviders and the High Cost of Health Care in America is now available from the University of Chicago Press. Order via Amazon or from your favorite independent bookstore.

Read moreAs much as we complain about insurers, drug companies, and government bureaucrats, it is our health care providers who are largely responsible for the cost and quality of care. About 52 percent of every dollar spent on health care goes directly to hospitals and doctors. Even this understates their importance. Doctors make decisions that affect roughly 80 to 85 percent of every dollar spent. The most expensive medical technology is not drugs or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); it is the physician’s pen.

Megaproviders like those listed in the table above assume the biggest responsibility for the state of our health system. They generate the lion’s share of expenses, and their executives are handsomely rewarded. Yet Americans are unwilling to take them to task. This might be understandable if megaproviders were slowing the pace of spending growth, but the facts that we will lay out suggest just the opposite. A recently published study by Zach Cooper and colleagues offers one compelling piece of evidence. The title of the paper hints at the findings: “The Price Ain’t Right? Hospital Prices and Health Spending on the Privately Insured.” Cooper et al. explain why health spending varies so much from one place to another, even after controlling for local differences in the medical needs of patients. They find that fully half of the variation stems from variation in provider prices. Prices are higher where hospitals have more market power, and prices increase when hospitals merge, especially when those hospitals are nearby and are likely to have been close competitors. This latter finding bears on an important theme of this book: health care is local, and megaproviders have a great deal of power in their local markets.

“The Price Ain’t Right” is just one of many studies documenting how megaproviders accumulate market power and use that power to drive up prices without creating offsetting efficiencies. Other studies find no improvements in patient outcomes; if anything, megaproviders contribute to lower-quality care. This means that wherever megaproviders dominate local markets, health care spending is higher, often much higher, and health care quality is no better, and sometimes lower. This is a big win for megaproviders, and a big loss for everyone else. If this is not bad enough, rather than engaging physicians in the process of reforming healthcare, megaproviders have caused them to become increasingly disaffected, disgruntled, and distrusting, making it harder to effect meaningful improvements in costs and outcomes. While the executives who put the megaproviders together may not have intended to cause such damage, they have failed to turn their size to our advantage. It is time that we recognize the megaproviders for the megaproblems they are.

Many economists, including Nobel Prize winners Kenneth Arrow and George Stigler, have offered a quasi-Darwinian view of markets. Firms dominate their industries by offering superior value to consumers. Some, like Walmart and Amazon, might have lower costs. Others, like Microsoft and Facebook, offer products and services that consumers covet. Whatever the means for value creation, the firms that create the most value survive and grow. Big firms are not perfect, of course—no organization is—but their strengths more than offset their weaknesses. In other words, we should not make knee-jerk objections to large, financially successful firms, because most big firms got that way by building better mousetraps.

As much as we complain about insurers, drug companies, and government bureaucrats, it is our health care providers who are largely responsible for the cost and quality of care.

This view rests on two big assumptions. The first is that all organizations face the cauldron of competition from current rivals and future entrants. The second is that at least some firms know how to create value for their customers. When both of these are true, competition can work its magic. Those organizations that best create value will usually outcompete their rivals, and a few may even dominate their markets. Thus, firms like Hyundai and Boeing are big because they know how to meet the needs of their customers. Hyundai makes really good small cars and, for the most part, Boeing makes the best large airframes for commercial air travel (although the 737 Max debacle shows how even the mighty can fall). There is nothing wrong when firms grow large because they deliver more value than their rivals.

After a combined seven decades of research, we have a difficult time embracing the quasi-Darwinian view in health care markets. As things now stand, too many megaproviders face too little competition, and too many of their executives seemingly do not know how to manage the complex process of organizing and delivering health care. What is especially troubling is that the two problems are intertwined. As we will detail, megaproviders came together out of the misguided belief that integration would generate scale economies and other efficiencies. It hasn’t happened. Instead, megaproviders have concentrated health care markets and have avoided the pitfalls of competition. Instead of effective managers facing the cauldron of competition, we have ineffective managers avoiding competition. So much for Darwin.

While many forces have indeed transformed the US health care system over the past century, they have not meaningfully transformed large hospitals. The organization, lines of authority, and workflows of the modern hospital are not all that much different from what they were decades ago, and the same inefficiencies persist. Hospitals have instead transformed their financial relationships with each other, and with other stakeholders. By merging to become megaproviders, hospitals have learned how to exercise local market power, charge higher prices, and exclude competitors. Some health insurers, especially Blue Cross Blue Shield, have accumulated power of their own, leaving the two sides battling over the division of the health care pie rather than diligently working to reduce the size of the pie. While the antitrust agencies do what they can to limit the accumulation of market power, and have enjoyed some notable recent successes, they are limited by a combination of factors that we will discuss. Competition policy alone will not rescue our health care system; and if it is poorly implemented, it will do more harm than good.

We believe that most health care executives sincerely want to reduce costs and improve quality. Unfortunately, many of them remain convinced that scale and scope are the answer. At the same time, even the most sincere executives cannot resist exploiting market power, bringing in more revenue, and investing in further growth. Like the cat chasing its tail, they may never realize the efficiencies and higher quality they seek, for the simple reason that size is no guarantee of performance. The result is higher health spending without commensurate higher quality. Is it any wonder that the American health care system is ailing?

Things are so bad that everyone seems to be seeking a cure; not just politicians. Corporate bigwigs like Warren Buffett, Jeff Bezos, and Jamie Dimon are trying to fix the health care system through innovative business practices drawn from outside health care. No matter how you look at the present situation, megaproviders, which have relied far too long on market power rather than effective performance, seem ripe for disruption. Given that the promise of disruption in health care served up by Clay Christensen two decades ago has yet to materialize, we doubt that the answers will come from the outside. The health care industry must heal itself.

*

Reprinted with permission from Big Med: Megaproviders and the High

Cost of Healthcare in America by David Dranove and Lawton Robert Burns,

published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2021 by The University

of Chicago Press. All rights reserved.