Featured Faculty

Walter J. McNerney Professor of Health Industry Management; Professor of Strategy

Member of the Strategy Department from 2013 to 2021

Professor of Strategy; Associate Director of Healthcare at Kellogg

Michael Meier

Healthcare is not just a big expense for individual households—it is also a huge expense for the public sector. Medicare and Medicaid make up a quarter of the federal budget; nearly 20 percent of state budgets goes to additional Medicaid costs.

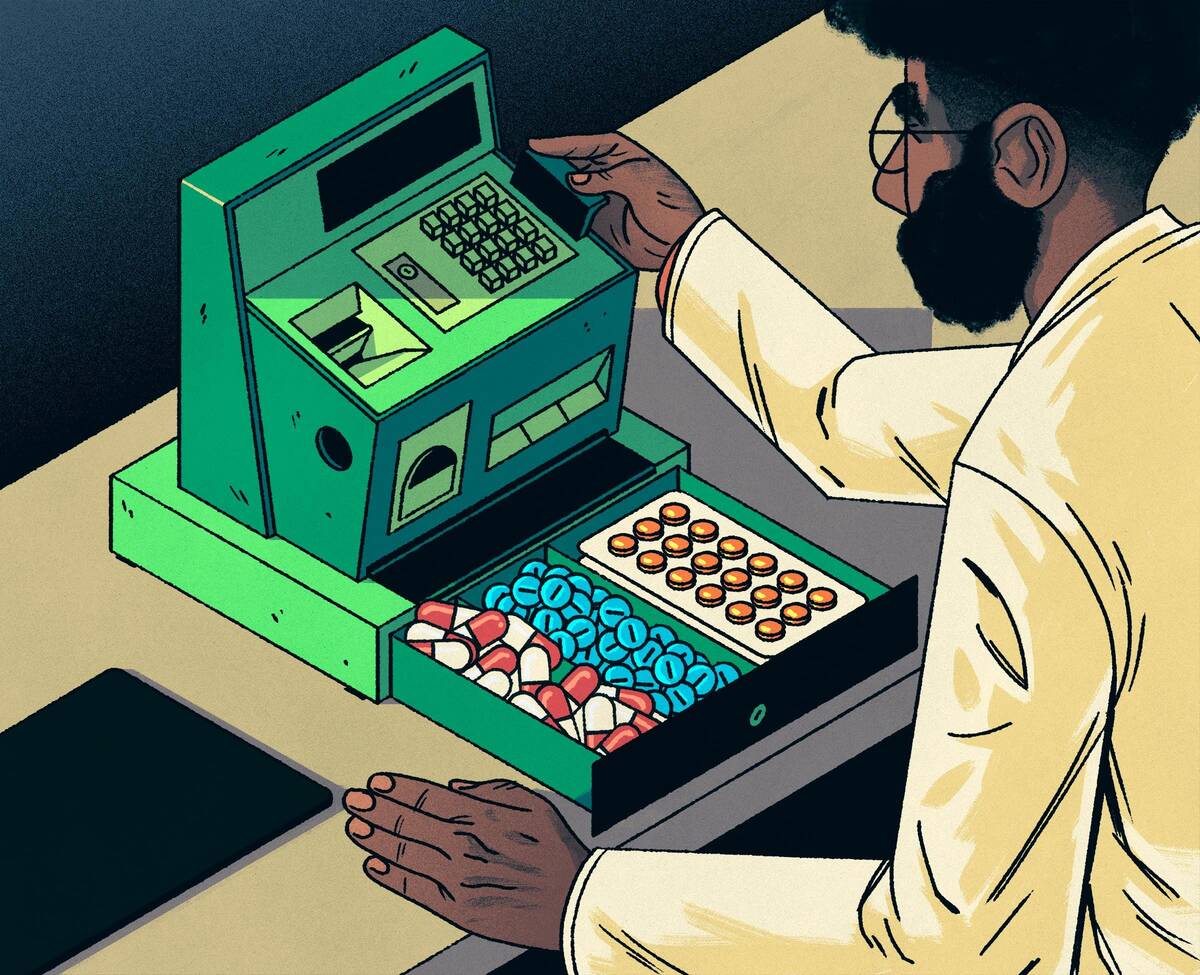

Rising drug costs are a particularly noticeable part of this expense for both consumers and policymakers. So a group of Kellogg researchers set out to understand whether private firms could use market mechanisms to control these drug costs. In particular, could shifting the administration of Medicaid drug benefits to private insurers provide some relief?

Yes, according to new research from strategy professor David Dranove, associate professor of strategy Amanda Starc, and research assistant professor of strategy Christopher Ody.

The researchers found that shifting the administration of Medicaid drug benefits to private insurers reduced spending by 22.4 percent, with no decrease in quality of care. The findings highlight the potential value of the public-to-private trend in healthcare.

“That’s a lot of money,” Starc says. “So savings is one motivation to study privatization of Medicaid. But it’s also about seeing how well markets can allocate goods and services. We have an effective market system for making sure people get the right consumer products—like ketchup—for a good price. But we have been reluctant overall to use a similar system for healthcare due to concerns about market failure.”

Privatization of Medicaid Drug Benefits

The private sector is playing a growing role in providing publicly financed healthcare. For example, one in three Medicare enrollees receives coverage through a privately administered plan. And the insurance exchanges established by the Affordable Care Act rely entirely on private insurers to provide coverage for people who are using public funds to subsidize the purchase of insurance.

“We don’t expect the government to come up with right prices in any other segment of the economy. So it’s crazy that we expect them to come up with them in healthcare.” —Amanda Starc

But the outsourcing of Medicaid drug benefits to private insurers represents particularly fertile ground for boosting savings and efficiency. The program, which provides healthcare for low-income Americans, covers about one in five US residents, or 68 million people as of late 2016. Moreover, price spikes for prescription drugs in general have intensified efforts to create and improve policies to drive savings.

“When it comes to providing prescription drugs to low-income Americans, there are lots of ways to do that,” Starc says. “But some of those will be better than others. When government shifts administration to a private firm that’s disciplined by the market, like all firms are, it will set prices for other supply-chain players [like pharmacies], which tells those players what to prioritize.”

Studying the Shift

Drug manufacturers are required to provide states with large rebates for prescription drugs that states purchased for Medicaid enrollees. Until recently, if private insurers covered Medicaid enrollees, then drug manufacturers did not need to provide these rebates. So the states retained the administration of Medicaid prescription drugs, rather than transferring it to private insurers through Medicaid managed care plans.

That changed in 2010, when the rules were modified by the ACA to enable states to collect drug rebates even when enrollees in government-provided plans were covered by private managed care organizations (MCOs), like HMOs and PPOs.

As more states transferred oversight of Medicaid drug benefits to these private firms, the researchers were able to analyze differences in spending from 2010 to 2016.

They compared spending in 13 states that transitioned the administration of Medicaid drug benefits to MCOs to spending in 16 states that did not outsource this administration.

As predicted, privatization of Medicaid drug benefits resulted in lower spending—a full 22.4 percent lower than in states that did not shift the administration to MCOs.

“That’s a huge number relative to any kind of spending change you ever see in healthcare,” Ody says. “It’s a best-case scenario for privatization because Medicaid leaves states’ hands tied in terms of what they can do to control drug-related spending.” For example, states can’t negotiate drug prices with pharmacies—as these are set administratively and can’t be altered easily—whereas private insurers can.

Not surprisingly, then, about 40 percent of the decrease the researchers observed in Medicaid drug-benefit spending was generated by MCOs paying lower prices to pharmacies for the exact same drugs for which states paid more—“the same pill from the same manufacturer,” Ody says.

The remainder of savings came from shifting patients from a branded drug to its generic equivalent or a closely related generic.

Ody notes that states can pull some of these same levers—such as requiring beneficiaries to try generics before branded drugs—but that MCOs have more resources and capability to do so successfully and are less subject to price-related rules. Indeed, when MCOs were forced to use a given state’s formulary (the established set of approved drugs, including first- and second-line medications), no savings were generated.

“Even if you’re the most motivated, brilliant person sitting at a state Medicaid office, if I tell you to set prices for 35,000 drug products, it’s going to be hard to get it right,” Starc says. “A private insurer can deploy data and a whole team to deal with this complexity and create much more sophisticated rules to set these prices—and has more incentive to get them right.”

Importantly, there seems to be little downside of the MCOs’ approach for patients, the researchers found. The insurers do not seem to be reducing benefits related to drugs for serious conditions such as cancer or heart disease, or cutting the use of certain drug categories wholesale to drive savings.

“They’re using a scalpel rather than a hatchet,” Ody says.

The findings support the general practice of trusting private insurers to manage drug-benefit administration for the government. Such privatization has already proven to work well at the federal level (as opposed to the state level examined here), for example, in the management of enrollees’ Medicare Part D drug benefits by private insurers.

Who Benefits Most from Privatization?

Since the end of the research time period in mid-2016, more states have transitioned control of Medicaid drug benefits to MCOs. Additionally, states are shifting other Medicaid benefits, including medical and mental health benefits, towards private firms.

“We expect this broad trend to continue more generally within Medicaid,” Starc says. “State budgets are tight, so it will allow them to boost savings and predictability in spending.”

Who are the biggest winners as a result of these savings?

The researchers agree that pharmacies are the likely “losers” when MCOs take over Medicaid drug benefits, because it means shrinking revenues and profits: “One man’s savings is another man’s lost revenues,” Starc says.

But exactly how much of the savings goes into MCOs’ or states’ pockets remains unclear.

“Privatization here makes the economic pie bigger for the state, insurers, and consumers,” she says. “But as far as who gets the biggest slice, it’s a muddled mix of those three.”

Regardless of the exact distribution of the value created by the privatization of Medicaid drug benefits, the big takeaway is that markets and private firms work well to reduce costs and boost efficiency in the critical, high-cost healthcare sector.

“We don’t expect the government to come up with right prices in any other segment of the economy,” Starc says. “So it’s crazy that we expect them to come up with them in healthcare. Private firms can simply deploy incentives and resources better to solve this complex problem.”