Podcast Transcript

Laura PAVIN: You’re listening to Insight Unpacked. I’m Laura Pavin.

Jessica LOVE: And I’m Jess Love. And up until this point, we’ve talked about the levers and pulleys that move some of healthcare’s biggest stakeholders. But now we’re going to address a question you’ve probably had this whole series, which is, what now? What would help better align everyone’s incentives with the healthcare outcomes we want?

PAVIN: Right. And before we go further, a bit of a refresh on what our system incentivizes. More or less, it tempts megaproviders to get even bigger to increase their power at the negotiation table.

LOVE: It incentivizes doctors to perform more (and more expensive) services.

PAVIN: It pushes insurance companies to minimize payouts unless they can pay off today.

LOVE: And it drives drug companies to pursue the next expensive, blockbuster drug, even if some of that money could be better spent on other drugs that can’t promise the same payday. You know, like lifesaving antibiotics.

PAVIN: This all makes healthcare in America very expensive. Which might actually be okay. We’re a very wealthy country, and we probably should be spending a lot on healthcare. The problem is that it doesn’t always seem like we’re getting a lot of value for that money, and healthcare remains out of reach for some people.

LOVE: This episode: Is there a better way? Can we get a better return on our healthcare dollars with our current system? Or is that not even possible without blowing it up and trying something new? And yes, that means we’re going to talk about universal healthcare.

PAVIN: But before we get into all that, I think we’d be remiss if we didn’t address one more player in this market: the patient. Because all of this—this whole healthcare system—is ultimately about them.

[music]

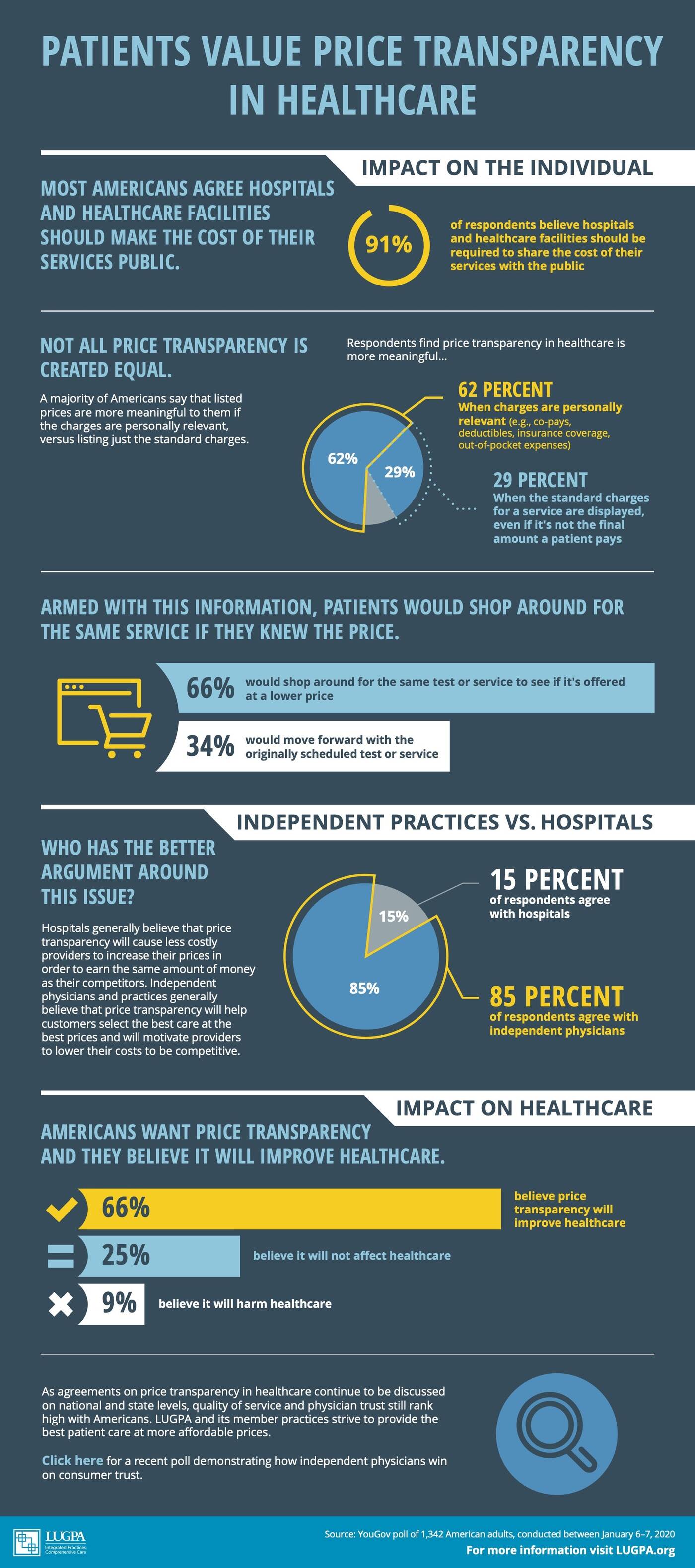

PAVIN: Okay, so patients in America. They are a player in this system! So it’s worth asking ourselves the question: Could patients themselves be taking matters into their own hands? Could they be better consumers of healthcare and really tell the market what they want?

I started thinking about the role that patients play after I mentioned to Professor Craig Garthwaite, the healthcare economist, that I got my allergy shots at a megaprovider. The one with the fancy lobby that gave me the red-carpet treatment for my shots: they let me kick back on their recliners, chat with my nurse gals, be waited on to make sure I didn’t have a crazy reaction.

And he was like, “wait a second, Laura, do you really need this more expensive option?”

Craig GARTHWAITE: Does that shot need to happen within the confines of the megaprovider? There’s a choice there. But you could have gone to an independent allergist.

PAVIN: Wow! Now, I feel really bad getting my allergy shots.

PAVIN: I was actually talking to one of my friends who gets allergy shots somewhere else, and she said her allergist basically kicked her to the curb with an epipen. So uh, yeah, looks like I am getting the premium package.

LOVE: Yeah, and suffice it to say that this isn’t exactly telling the system that it needs to cut down on the bells and whistles to make things cheaper for patients.

PAVIN: Thanks, Jess.

LOVE: This isn’t us singling you out as the problem patient, though. As a group, patients—as in, all of us—regularly ask for things that we want but don’t need. Like, if you remember from our doctor episode, we might ask to have bloodwork done for dubious reasons. And then if the doctor says “no,” we’ll punish them with low ratings on social media.

LOVE: And we generally don’t like being told to change, even if that change would save the system money. We talked about that in the insurance episode when HMOs came in and tried to gate-keep which specialists patients could see. That didn’t go over well. And we know that patients don’t really prioritize preventative care when they pick an insurance plan. That’s probably not a great thing for long-term costs to the system.

All of these are choices we, patients, make every day. And in ways large and small, they drive up healthcare costs. And they make us happier! But they might not make us any healthier.

PAVIN: Right. But, Jess, to be fair to patients, it’s also true that being a good consumer of the American healthcare system is basically impossible. And I know this because I have a friend who, unlike me, tried.

Conor PARKER: Hello? Oh my God, I figured it out.

PAVIN: This is Conor Parker. He’s been a friend since college. I talked to him over Zoom about an experience he had a few years ago. He was playing softball, running down a ball in the outfield.

PARKER: … running fast, very, very fast like a gazelle. And as I’m slowing down to pick up the ball, I feel like a pop in my knee.

PAVIN: He plays through. The next day, it’s swollen and sore, so he knows he has to see a doctor to figure out what he’s dealing with. But getting a diagnosis was tough. He made six different visits to different healthcare facilities and imaging centers, all to learn one piece of information: he had a torn meniscus.

Months later, the bills start coming in. Six of them.

PARKER: …a couple hundred dollars, a thousand dollars, from all these different people that I had kind of thought was already taken care of, but it wasn’t. So some of them I wasn’t even expecting. I hadn’t realized that the imaging center was separate from the doctor who sent me there.

PAVIN: It seemed like a lot of money for one diagnosis. But, he thought, lesson learned. He needed to research what things would cost before he went in. That’s how he approached the surgery he ended up needing. When he found a doctor he liked, he brought his insurance information to the office to make sure they were in-network. They were, the office said, and Parker was like, “Great! Now we can nail down my coverage for the rest of this process.” He talked to the medical assistant about it.

PARKER: So I started off with her, asking her a whole bunch of questions. One of the questions being, “can you give me an estimate on exactly what the costs of this whole thing are going to end up being?” So her answer to that initially was, “no, we can’t really tell you. You need to talk to your insurance company.” So then I called the insurance company, I’m asking them, and their response was basically, “we can’t tell you. You have to ask your doctor.” So I’m kind of getting passed back and forth a little bit, and eventually the insurance basically says, “okay, the thing is we can’t tell you what we’re going to cover until we get the medical codes sent to us by the doctor that we run through our system.”

PAVIN: In healthcare, providers and insurers communicate to each other in code. Medical codes. They correspond to all the things that providers do so that they can be billed properly. Parker’s insurance said it needed those codes to figure that out. So he gets them from the doctor’s medical assistant, and then he ends up needing more codes because, surprise, the hospital and the anesthesiologist bill separately. He gets those codes, and then his plan tells him, “sorry, that anesthesiologist isn’t covered, you’ll have to pay a couple grand out of pocket for that.”

PARKER: And so at that point, I started being like, well, how can I get one that’s covered? Do I need to ask the doctor to change the venue to a different hospital that has an anesthesiologist that’s covered, or is there another one that works in that hospital? Like how can we problem-solve this? And they came back to me the next day and said, “actually, the thing is that that whole hospital isn’t covered, so that’s why the anesthesiologist isn’t covered.”

PAVIN: Parker calls the doctor’s medical assistant back and says, “hey, my insurance says that the hospital where you do the surgery isn’t covered. Can we do it somewhere different?”

She says, “that’s bizarre. If we’re covered, everyone we use should be covered. We’re all part of the same network.”

PARKER: So she goes back and starts looking into it, and then it comes back that actually that doctor is not covered. So no one in the process is covered.

PAVIN: The whole reason Parker went with this doctor was because his office said he was in-network. But they made a mistake, and he was out-of-network the whole time. So the procedure went from being $3,000, which was his deductible, to somewhere around $18,000.

PARKER: And then everyone said, so do you still want to do it?

[Parker and Pavin laugh]

PARKER: The whole thing that I went through was all for naught. I never ended up getting it fixed. I still have a partially torn meniscus in my leg.

PAVIN: Parker guesses he spent between 12 and 18 hours on the phone trying to learn this one thing. The whole thing annoyed him so much that he just decided to not fix his torn meniscus at all.

LOVE: Jeez.

PAVIN: Yeah. But I think the saddest thing about this story is that it sounds familiar to a lot of us patients, right? The hours-long game of telephone, the layers and layers of people involved in the process, the codes, the billing nuances of all of these separate things that you just assumed were all part of the same gig.

LOVE: Yeah. And okay, to be fair to the system, it is hard to price something that’s so unpredictable. You have no idea what’s going to happen once the patient is in the operating room.

PAVIN: True, but this leaves us with this bind: How can prices work in a market like this? When we can’t even properly shop—an activity that is the clearest way to tell the market what is and isn’t worth paying extra for? It all makes you wonder if we should just gut everything and start over with a system that isn’t quite so complex? Should we, perhaps, go with that solution we always hear brought up on the presidential-debate stage every four years?

LOVE: We’ll go there next.

Senator Bernie SANDERS: Today we begin the long and difficult struggle to end the international disgrace of the United States—our great nation—being the only major country on earth not to guarantee healthcare to all of our people. As proud Americans, our job is to lead the world on healthcare, not to be woefully behind every other major country.

[applause]

LOVE: That’s Senator Bernie Sanders talking about Universal Healthcare and introducing the Medicare for All Act of 2017. We know how that turned out.

But it’s an alluring idea, right? Get rid of our convoluted private health-insurance industry with all of its imperfections and replace it with something simple. All Americans get equal access to care; all Americans can understand it.

PAVIN: Sounds great to me! Europeans seem to like it. I think? That’s the narrative, at least. That they have it a lot better over there, as far as healthcare goes. I wanted to see if that was true. So, Jess, mind if I take over for this stretch?

LOVE: Go right ahead.

PAVIN: Alright, so I wanted to know what it was like to experience healthcare in a European country, so I called someone.

Alexandra SALOMON: I’m so sorry.

PAVIN: No, oh my God, no, you’re so busy.

[fades under and continues]

PAVIN: This is Alexandra Salomon. She’s a former editor of mine. She lives in Chicago but spends a lot of time in Italy because her husband’s from there. Her husband’s name is Enrico Scaffai. He designs hospitals, oddly enough.

Anyway, I talked to both Salomon and Scaffai. And I asked, “how does Italy’s system feel compared to America’s?”

For them, they said, it felt more communicative.

[fades back up]

SALOMON: I noticed that, like, you talk to them on the phone, like, it’s no big deal to talk to the doctor on the phone. So my kids spend the summer at my in-laws’. And my mother-in-law’s always on the phone with the family doctor. Like, their family doctor has met my kids. And it stuck with me because I know what it takes for me to get to actually speak to my pediatrician. You know what I mean? You got to, like…

PAVIN: You can never get them on the phone.

SALOMON: Yeah. And, like, again you’re here, you’re sort of forced to go to urgent care or the ER a lot of times for things because you can’t access that sort of more basic preventative daily care.

PAVIN: The family doctor seems to play an important role in Italy. They run interference a lot to keep you out of the hospital. Obviously, we have family doctors in the U.S., and they do that, too. But the relationship sounds different in Italy. Here’s Scaffai.

Enrico SCAFFAI: The family doctor in Italy still is considered someone where you’re connected closely. Kind of like family. You relate to them as part of your … kind of like a relative.

PAVIN: Scaffai says his friend’s dad was the town doctor where he lived. He saw how he was treated.

SCAFFAI: The people bring over prosciutto, mozzarella. They say they take care of you. At the end of the year, they go there and say, thank you, appreciate you, like you’re …

SALOMON: Everybody knows him.

PAVIN: It’s a familial kind of relationship. One that I cannot fathom having with my own doctor.

The familiarity Italians have with their system extends even to the pharmacy.

SALOMON: The pharmacy is an amazing experience in Italy. I love going to the pharmacy. There isn’t Walgreens and CVS where you’re getting…

[crosstalk]

SCAFFAI: Yeah, yeah. That’s a good point.

SALOMON: But you can go to the pharmacy, you can show them: “I have this rash.” They’ll look at it, you can get a first line …

SCAFFAI: There is a relationship with them!

SALOMON: … of care. They just kind of approach it much more like a medical person. And they can often recommend something. But there are certain things that here would be prescription, there you can just do over-the-counter.

SCAFFAI: They show, I say, humanity, compassion, empathy.

PAVIN: You can’t go to a, you, Enrico, would not feel comfortable going to a Walgreens and asking the pharmacist about a rash?

SCAFFAI: No, no. They would say, what are you asking me?

[Salomon laughs]

PAVIN: And I’m not speaking for myself here or anything, but I’d imagine that’s saved people from doing some panicky internet searches about a bug bite. That seems pretty valuable.

But the cherry on top of Italy’s healthcare system is this: It’s a lot easier for patients to figure out, which is kind of the opposite of what we have here in America. You don’t have to play a weird game of telephone between your insurance plan and the provider to figure out what’s actually covered and what you actually owe. For the most part, you aren’t really involved in the billing process.

Like, okay, say my friend, Conor Parker, got his surgery done in Italy to repair the torn meniscus in his knee. The way it might work is that he would go in, the provider would do the surgery, and the provider would get reimbursed by the regional government for that. Because in Italy, the central government hands the reins over to its different regions to handle the mechanics and financials of its healthcare system. By the way, this is still a single-payer system: the central government is funding it all, but it delegates the legwork to local health units.

PAVIN: And of course, in Italy, you aren’t worried about suddenly learning you’re on the hook for an $18,000 bill, either. You might have some kind of copay, but it would be small.

This is a massive upside, if simplicity is what you want in a system. And who doesn’t want that?

* * *

PAVIN: Unfortunately, it’s not all roses for the Italians.

Salomon was telling me that her mom, who is American and lives in the U.S., had just had a health scare here in Illinois. It required a surgery that couldn’t be scheduled until weeks out. Salomon knew her mom couldn’t withstand that, so she found a doctor at a different hospital to do it sooner. And it worked out.

I wondered if she thought the same could happen in Italy.

PAVIN: If your mom had to have what she had done here in Italy, I am curious to know if, would you have gotten the same sort of immediacy? Well, that you pushed for obviously.

SALOMON: I would think so in an emergency situation. And I certainly wouldn’t be fearful, let’s say, that the care wouldn’t be good.

SCAFFAI: Hmm.

PAVIN: If you couldn’t hear, that was Scaffai expressing some doubt that the care would be good. It catches Salomon by surprise.

SALOMON: You would be fearful in Italy?

SCAFFAI: Hmmm. Kind of strange because I never asked myself. Probably, I would be nervous, definitely.

SALOMON: You seem to say that here, you wouldn’t be so worried that you wouldn’t get somebody who was capable. You would be worried about that in Italy?

SCAFFAI: I don’t know. Sometimes. I don’t know.

SALOMON: Hmm.

SCAFFAI: Ehh.

[Salomon laughs]

[Long silence]

SALOMON: Do you think the quality is uneven there?

SCAFFAI: Okay, well there’s one thing, maybe. When you are in Italy, sometimes, and that’s like I’m telling you this, the man on the street again. But some of the positions you find in these hospitals, they’re very political. They are there because we are very political. Political doesn’t go along with, I am the best doctor here and that’s why I have this position. That’s the only thing. It doesn’t mean that you’re in the hospital: you’re going to be good. It might be also because you have political connection.

PAVIN: I can’t back up Scaffai’s impression with any hard data, that bureaucratic savvy carries more weight than medical moxie in Italy. I can say that Italy has rigorous standards, regulations, licensing, and accreditation requirements in place that all providers and facilities have to follow.

But I can also say that politicians do decide who runs each local health unit. And more broadly, Italy does have a history of politicians giving jobs to supporters, friends, and relatives. It’s a practice called political patronage. At the same time, Italy does not have a strong history of using merit to promote people. Anyway, you could see how that might make you wonder, is this guy, in this healthcare system, really a good orthopedic surgeon? Or is he buddies with the guy who knows the governor?

[music]

PAVIN: I think here is where we need to talk a little bit more about what universal healthcare is, because it’s kind of a weird animal that I don’t think Americans fully understand. I sure didn’t.

But what does America know about universal healthcare, anyway? I found someone who fancies himself a proxy for an informed American.

Jacob CONNORS: Umm.

PAVIN: My husband, Jacob Connors. I ambushed him so he couldn’t prepare.

PAVIN: I wanted to kind of understand, like, what is people’s understanding of what universal healthcare is, like, how it works? What’s your rudimentary understanding of, like, the mechanics of that?

CONNORS: Expanded Medicare.

PAVIN: Go on.

CONNORS: Well, I think what they do with Medicare now is it’s hosted through.… They have relationships or deals with private insurers? I honestly don’t know how Medicare works.

PAVIN: Hahahaha. No, Jake.

PAVIN: Yeah. So, you see, it was kind of a trick question because the answer is, there is no one way that universal healthcare works. I just wanted Jake to be wrong.

CONNORS: Well you kind of buried the lead.

PAVIN: Okay, so, Italy’s healthcare system? This is just one iteration of universal healthcare. Because the thing that makes universal healthcare universal healthcare is basically this: people can go to the doctor or the hospital there and not have to worry that it’ll send them into financial ruin. That’s it. That’s what universal healthcare means. But the way you get at that is different from country to country.

Perhaps the most well-known system is known as “single payer.” There are other, non-single-payer versions of universal healthcare, but for now, for simplicity’s sake, this is the system we’ll focus on today. This is the one that Senator Bernie Sanders and Senator Elizabeth Warren were boosting during the 2020 presidential race. And this was probably the one that my husband, Jake, was thinking of.

“Single payer” means that the government is the single main entity that pays for its residents’ healthcare services. But that doesn’t mean the private sector isn’t involved at all. Some governments contract with private doctors, hospitals, and clinics to do the care.In Canada, the majority of its providers are private. They’re just paid with public money.

Private insurance can have a role to play in these single-payer systems, too. It’s just more of a topper for the public insurance you get.

All in all, the upshot for these single-payer systems is that the government pays for the basic, agreed-upon level of service for everyone.

Italy is a single-payer system with some of that private involvement.

For example, one of the things that falls outside of Italy’s public healthcare plan is routine dental care. It’s not something public insurance will cover, so you either need a private insurance plan, or you just pay out-of-pocket.

But, for this American, that doesn’t feel like a huge deal, right?

Well, there are other downsides to single-payer that you wouldn’t expect. Like perceptions about their quality. We heard that when we talked to Scaffai about Italy’s system when he mentioned he was a little more nervous about the quality of certain doctors there.

And Italy’s system, like some other single-payer systems, also has bottlenecks.

Salomon again.

SALOMON: My mother-in-law had cataracts. Waited. It was probably, I don’t know, three months, four months. My mom did her cataracts. My mom wanted to get her cataracts done. She called and then the next week she got her cataracts taken care of, right.

SALOMON: Enrico, one of his cousins who’s had bad scoliosis all her life and needed a major surgery on her back, I do remember because it was like a year at least maybe that she had to wait for that operation.

SCAFFAI: It was quite a while.

SALOMON: It was a long time.

PAVIN: Wait times are an even bigger issue in Italy right now in part because it’s been having some problems retaining medical professionals. This is because of, quote, “uncompetitive salaries, crumbling infrastructure, long hours, and bureaucracy—making it hard to attract foreign talent.”

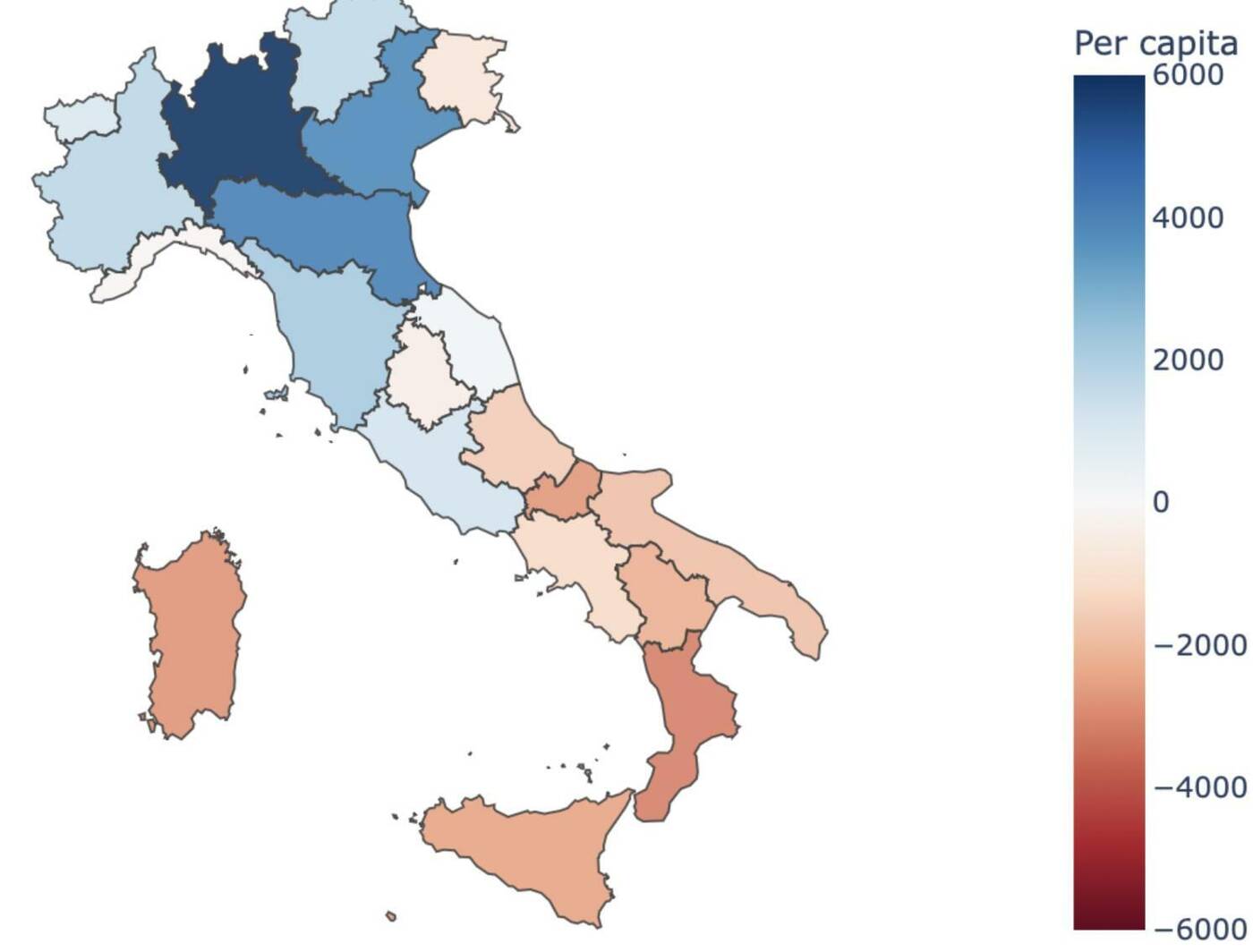

Another problem Italy has that might surprise you is care disparities. The care you get depends on where you live. Part of the reason is because Italy’s local health units can invest private resources on top of the public ones they get. In practice, that means the more affluent north tends to be better-funded than the less-affluent south.

[music]

PAVIN: And look, I fully acknowledge that these pros and cons are breezing past a lot of sensitive nuance about single-payer systems and universal-healthcare systems in general, because again, they are all incredibly different. But the fact that there are cons is important to keep in mind. Especially the part about there being disparities in a single-payer system at all. I certainly didn’t expect that.

Healthcare economist Craig Garthwaite had a “yes, and” for that realization. Remember when Scaffai was worried about doctors using political connections to land jobs? Garthwaite says politics can lead to something even more consequential in single-payer systems.

GARTHWAITE: My sense in single-payer systems is more that, where the politics comes in is we don’t ration based on money. We ration based on political connections. And so if you were unable to get the surgery that you wanted right away, you could use your connections to get around it, but the average person couldn’t. And so, like, it ends up that richer people tend to do better in getting access in those systems for reasons that aren’t about money, but around the things that are associated with money, which is power and power inequality.

PAVIN: Humans, we always find a way to gain an advantage, don’t we?

Kellogg Professor Amanda Starc says these systems aren’t that categorically different from what we have here in America, anyway.

STARC: When it comes to delivery, lots of these other European countries, they also have a mix of public and private delivery just like we do. They might rely more on public providers than we do, but nonetheless, they have this mix of public and private. And so, I always think of this as being more on a spectrum than an either–or. And I’m not sure we’re at the right spot on that spectrum, and I’m not sure they’re at the right spot on that spectrum.

PAVIN: Because, of course, America also has a mixture of public and private.

But the important part to know is that our particular system values speed and cutting-edge treatments over providing everyone with some agreed-upon level of care. We might not say this out loud, but that’s the message our system signals.

And that’s actually a really key point: that we don’t say this out loud.

Because Professor Craig Garthwaite thinks Americans need to say things out loud. We need to have a deeper conversation, as a culture, about what we do want from a system before we make any monumental changes. Because every system, including a single-payer system, does come with its own set of trade-offs.

GARTHWAITE: Americans don’t like being told they have to wait for things, just full stop. And for most very serious things in the U.S. you’re going to get it treated faster here. Regular run-of-the-mill stuff might take just as long as another country, but if there’s an acute thing that has to be done, we’re pretty good at scheduling it here. We’re pretty good because we’ve built up the capacity to make it profitable to have it, and so if you’re 80 years old and you break your hip in the United States, we’re going to find you a new hip pretty quick. Because we’re going to get paid a bunch of money to give you a new hip really quick. In another culture, there might be a conversation about, do you need a new hip or is this the end of the road here? And we’re going to sort of wind this down.

PAVIN: A single-payer system would require us to have these conversations, because we all pay for it! So we’d all have to decide what is economically feasible to treat, and that could lead to its own inequities.

Garthwaite again.

GARTHWAITE: We don’t have that conversation in the United States ever. We never have that conversation about, is it cost-effective to do surgery on someone. We sometimes have the conversation about whether it’s actually your body can have the surgery. Even then, we probably don’t have that conversation as much as we probably should. And so we’re doing pretty serious surgeries on pretty old people, but other cultures are going to have that question about, we’ve got X amount of resources that we’ve got to spread out over Y amount of people and who should get it and maybe the 18-year-old should get it before the 80-year-old does.

PAVIN: There actually was a conversation had about this in America. Around 15 years ago.

[news clip]

Barbara WALTERS: President Obama stood before joint session of Congress and said there was no such thing as a death panel. Is he a liar?

Sarah PALIN: He’s not lying in that those two words will not be found in any of those thousands of pages of different variations of the healthcare bill. No, “death panel” isn’t there. But he’s incorrect, and he is disingenuous.

[fades out]

PAVIN: That’s Barbara Walters interviewing Sarah Palin, who was then the 2008 Republican vice-presidential candidate. They were talking, of course, about “death panels.” In this case, it referred to a measure that would have paid physicians to talk to Medicare patients about living wills and end-of-life care options. But Palin’s spin suggested those conversations would spiral into decisions around who was worthy of living. The provision never made it into the final healthcare act. Americans just really didn’t like their government having any say in their healthcare journey. And they don’t like being told “no.” Which honestly seems to be a theme here.

The point is all healthcare systems have trade-offs, prioritizing some things over others. And before we call for drastic changes, it’s probably worth having a serious, good-faith conversation about what any trade-offs would look like.

We haven’t had this conversation yet. But, who knows. Maybe, someday, we will.

[music]

* * *

PAVIN: Jess? You still there?

LOVE: I am.

PAVIN: Okay, great! Because now I’m going to hand this over to you, because you’ve been thinking about what could actually solve for the problems we have with our U.S. healthcare system. So, with that, the stage is yours.

LOVE: Okay, so right now, we’ve got the system we’ve got. Our system is really complex—including in a lot of ways we haven’t even come close to touching on. But maybe there’s a benefit to this complexity. Because it means there’s a lot of experimentation going on—to build a better mousetrap, to come up with some model that can get quality care to more people without sacrificing what does work about our system. Maybe we just need to figure out which of these experiments is working the best, and then replicate it across the country.

LOVE: There was one system, in particular, I was really interested in hearing more about. Our economists mentioned it a bunch of times.

[montage of them saying Kaiser]

LOVE: That system is Kaiser.

[Commercial]

Some healthcare experiences can be fragmented and impersonal, with the responsibility on the patient to make it work. But at Kaiser Permanente, one of the nation’s leading nonprofit integrated healthcare systems, everything works together to provide equitable, high-quality, affordable care and coverage that support the unique needs of nearly 13 million members.

[fades out]

LOVE: Kaiser is a healthcare system largely on the West Coast. It’s been around since the ‘30s, actually. And it’s unique because Kaiser is basically the doctor, the hospital, and the insurance plan, all lumped into one. There’s some nuance there; I should say, there’s a couple of different tax entities involved. But what this does is it puts everyone in the system more or less on the same team, unlike the more common dynamic of payers, providers, and hospitals fighting like a pack of wolves for the same piece of meat.

We spoke to Murray Ross about it. He’s the vice president for Kaiser’s institute for Health Policy and Government Relations.

Murray ROSS: I got to Kaiser in 2002. Most of my career at KP was spent, I don’t want to say proselytizing, because that’s not quite the right word, but explaining Kaiser Permanente to the outside world.

LOVE: If you can’t tell, Ross is one of these people who really, really loves the Kaiser model.

What’s fascinating about Kaiser is that it runs mostly on premiums, you know, that monthly dollar amount you pay an insurance company for baseline coverage? At Kaiser, premiums are a key revenue source, the fuel that pushes the engine. And that forces Kaiser to focus more heavily on preventative care, because they want to hold onto as much of those premiums as they can. In the Kaiser model, they can’t bill you extra if you need a hip replacement. That’s what you paid the premium for.

So, unlike the status quo I’m used to, where the hospital and the physician group and the insurance plan are all bickering for their slice of the healthcare spending pie, Kaiser’s “fights,” so to speak, happen internally.

ROSS: So then you’re in a negotiation, well, how much money goes to the medical group, how much goes to capital, how much goes to philanthropy, how much goes to reserves?

LOVE: They’ve got this set amount of money to divvy up among themselves. So if you’ve got a surgeon doing expensive procedures, that’s less money for everyone else. Everyone in the Kaiser system would really just prefer patients not need those surgeries in the first place, so the incentive is prevention.

But Kaiser’s reliance on premiums is only part of what motivates them to prioritize prevention.

Speaker 2: So the other piece is that the physicians are salaried employees of the medical groups that they own. The salary piece changes everything because it’s no longer paying by the service.

LOVE: Physician salaries seem to be the crown jewel in all of this. Ross says, it’s not like they get paid more for doing more stuff, like treating your colon cancer that could have been caught earlier. Doctors would like to make sure things don’t get to that point. And Ross says that’s resulted in some meaningful programs. Like their colorectal-cancer-screening program.

ROSS: It’s at least a decade old now, and that started from our gastroenterologists saying, we’ve been shouting as loud as we can to get people coming in for colonoscopies. And basically everyone who wanted a colonoscopy already had one. So how do you drive up your screening rates? Well, luckily the technology changed, and you could start doing these, the fit kit, the fecal immunoassay test, and you mail it out to the patient’s home, they mail you back a sample, you tell them whether you found anything concerning. And, we were in position to take advantage of that technology because our gastroenterologists aren’t paid on the basis of how many colonoscopies they do. whereas in fee-for-service, that’s how you make your money.

LOVE: Kaiser says that its overall approach reduced colon-cancer deaths in its region by almost a quarter over the course of 7 years.

* * *

LOVE: I was downright giddy after our conversation with Ross. Because it felt like, there it is! There is our solution! A real incentive to practice preventative care, and one that has to make do with a fixed amount of money. And that everyone liked! They really liked it! This sounded revolutionary to me.

We circled back with David Dranove about it, who you might remember wrote a book on healthcare systems. So we asked him: Can we just make everything like Kaiser? He said we were not the first to ask this.

David DRANOVE: When I first started studying health economics over 40 years ago, it was already understood as far back as the 1960s that Kaiser was the gold standard. That they had lower costs; they apparently had comparable, if not superior, quality. And there was a lot of research trying to figure out why. When they’ve tried to do this in other markets, they haven’t been successful.

LOVE: He said Kaiser’s tried to expand. And they’ve had some success, but not like you would think for a model that seems to work really, really well on the West Coast.

ROSS: We were in North Carolina.

LOVE: Murray Ross again.

ROSS: And that situation has been well-documented. But basically it was hostility from the local medical establishment, not a whole lot of support from the local policy establishment. And I don’t think KP made the convincing case to employers.

LOVE: I found a journal article about all thisin the National Library of Medicine. In the ‘80s, North Carolina was worried about healthcare costs, and they knew Kaiser was good at controlling them. So they recruited the system to come on over. It did, and things seemed like they were working out. It was profitable for a few years, but things eventually went south and they left the market.

Kaiser had similarly bad luck in Kansas City, New York, New England, and Texas.

We asked Dranove if he had thoughts on why Kaiser failed in all these areas. And he said we actually don’t have any data to explain what makes Kaiser work in one place versus another. But, when we pushed him a little more on this, he turned to history. He said Kaiser came up during the Great Depression and World War II, which was a time when the healthcare industry was still figuring itself out.

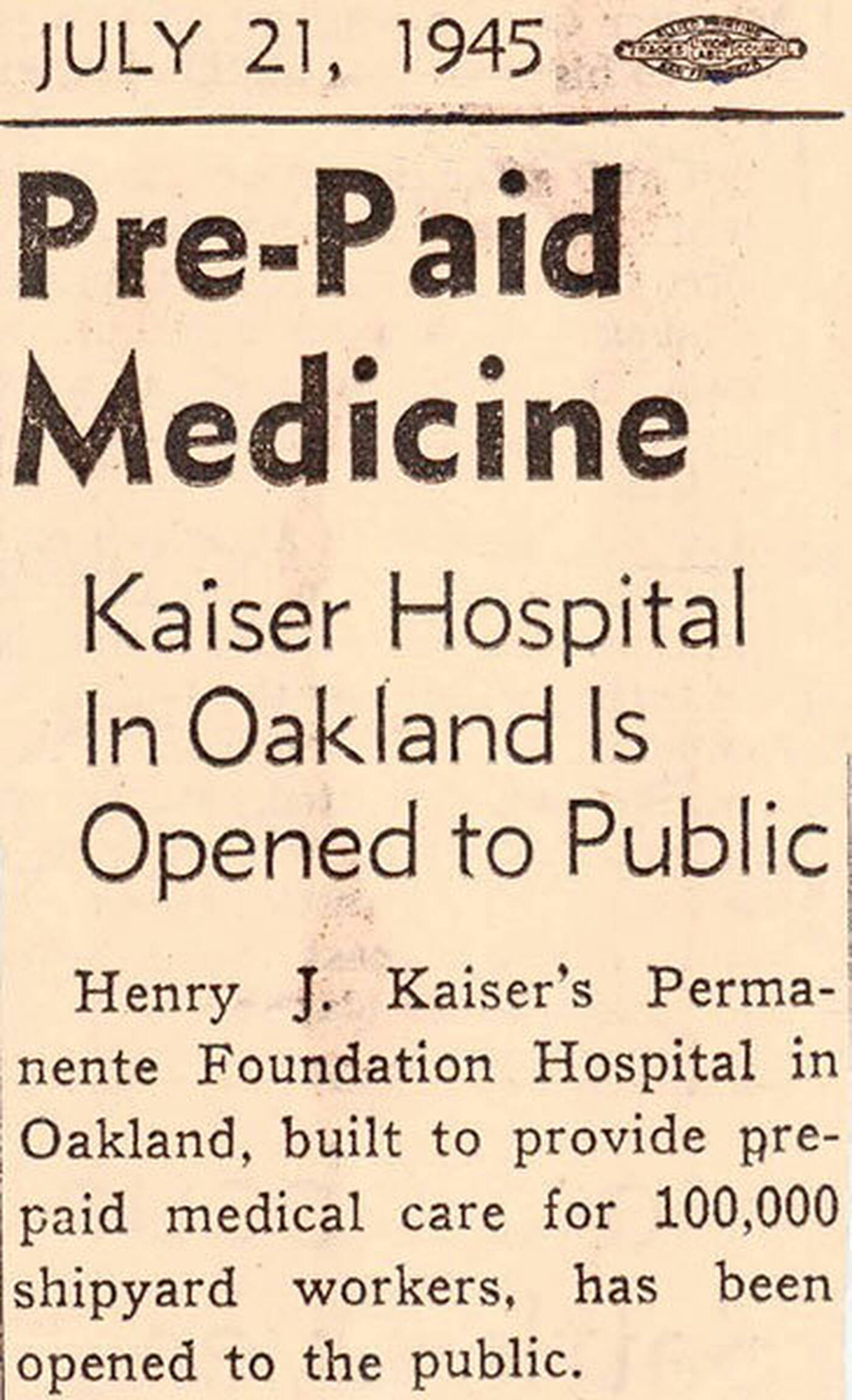

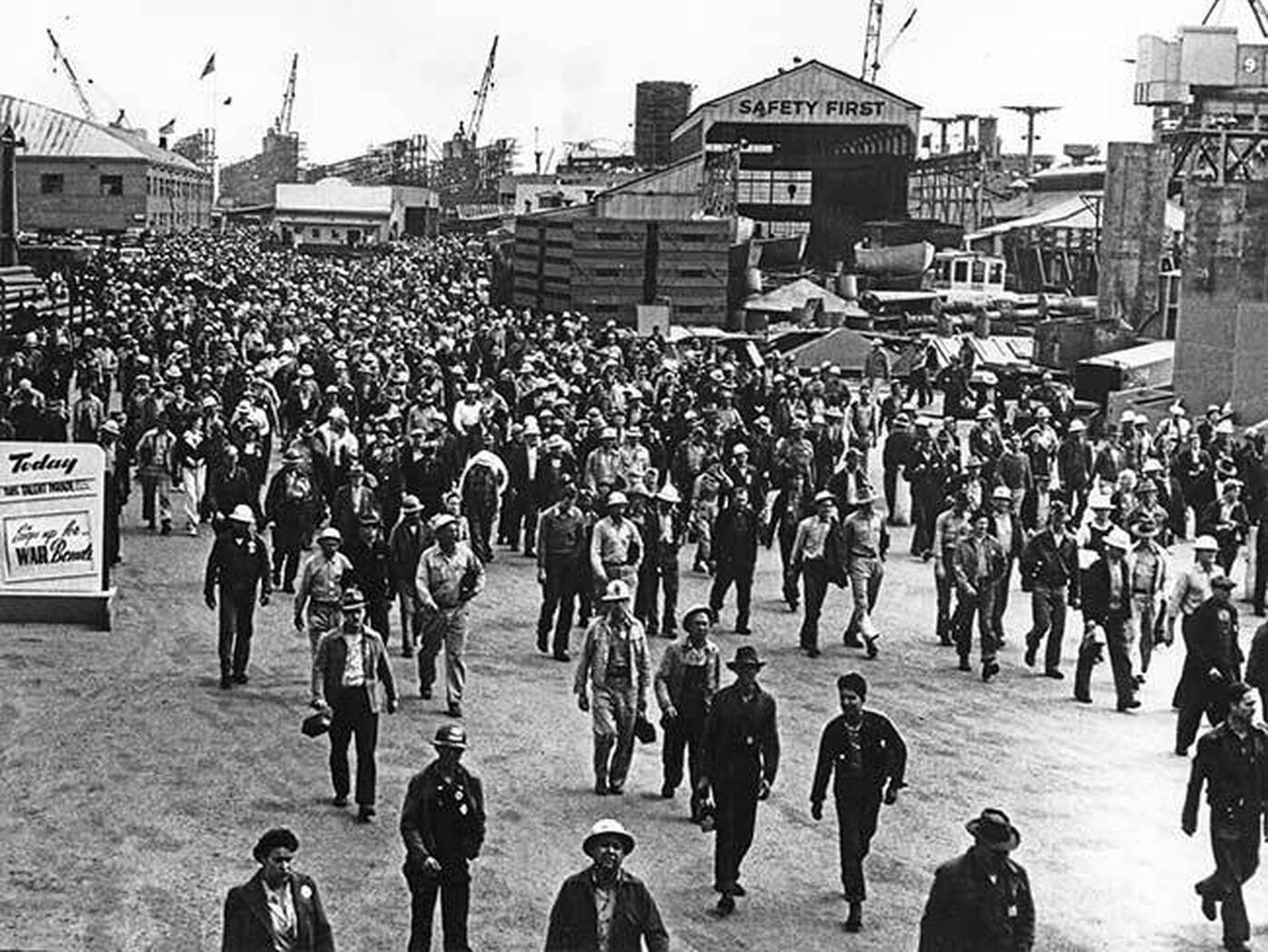

DRANOVE: Kaiser started because the company that was building battleships for the Navy, which was Kaiser, couldn’t find healthcare providers. So they provided their own healthcare.

LOVE: It was a doctor at a hospital offering prepaid care tothousands of industrial workers. Which was great from a scale perspective: you need a big risk pool of healthy people for the prepaid model to work. Gotta spread that risk to turn a profit. And it did work. And it kept working.

DRANOVE: And they had decades to sort out which doctors should work for Kaiser and which shouldn’t. And as they opened it up to the public, some consumers found it was right for them, others found it wasn’t right for them. So there was a lot of selection of both doctors and patients.

LOVE: The Kaiser model got buy-in early, before anyone knew any different. And it got the scale to make it viable.That scale, Craig Garthwaite tells us, is several hundred thousand patients. All of these conditions are very specific to Kaiser’s recipe. Dranove again.

DRANOVE: How do you get that kind of selection in other markets? That’s not easy.

LOVE: I want to pause for a second to reflect on something that felt like a revelation in this conversation. Kaiser got its start around World War II. And it’s funny because this is when a lot of different healthcare systems around the world got started. Right? We talked about this in our third episode. That’s the moment when an employer-payer system took off in most of the U.S., while a single-payer system took off in Europe. And the Kaiser model took off at the same time. And in all of these places, the thing that got started seventy-five years ago, built from nothing, is still recognizable today.

And I think what that tells us is, it’s really hard to make drastic changes to whatever system is already entrenched. It’s not impossible to adapt to a new system. Kaiser has had some success in D.C., for instance, where it landed itself on the federal-employee benefit’s package. That’s how, after a long struggle, it eventually got scale there.

But usually, convincing patients to make a shift to the unknown is hard. And not just patients. Ross says that convincing healthcare professionals who’ve been in one system to jump to another is a tough ask.

ROSS: The corpus of physicians and hospital executives, they’ve been at their jobs for 15 to 20 years. Fee-for-service is what they know. And if you’re going to a 55-year-old hospital CEO and saying, “we’d like you to engage in a completely different financial arrangement that you’ve never experienced before and won’t know how to address, and oh by the way, it might go away in three years if the employer decides they don’t like it,” You’re going to say, “nah, I’m good.” Right?

Same thing with physicians who have been taught. I mean if they didn’t learn it in medical school, they learned it pretty quickly afterwards, that you need to bill for your services and you also need to generate services. Whether that’s practice location…. I’m not suggesting anything illegal here, but if you’re an orthopedic surgeon, maybe you want to live in Vail.

So everyone talks about all the problems with fee-for-service, but we can’t get anyone to say, okay, but I’m going to stop doing it that way and I’m going to take a salary cut.

[music]

LOVE: So Kaiser is one model—albeit a model that seemed to be easier to launch 75, 80 years ago than today. But there’s another interesting healthcare experiment going on right now. And that’s vertical integration. Big insurers like UnitedHealth Group, Aetna, and Humana are vertically integrating, meaning they’re busy acquiring other companies at every level of healthcare. They’re buying their own pharmacies, pharmacy benefits managers, and providers to ensure that they, and they alone, can handle all aspects of a patient’s care.

And in theory, vertical integration could improve the system in similar ways to Kaiser. Here’s Craig Garthwaite again.

GARTHWAITE: It aligns the incentives well, and particularly, it’s the integration between the payer and the provider that I think is important. I make more money if I provide less care, which in theory is good.

LOVE: When the patients are healthy, vertically integrated systems save money because they don’t have to shell out for as many expensive hospital stays. Sounds a lot like Kaiser, right? More or less. The one key difference here is that Kaiser owns its own in-patient hospitals. Vertically integrated systems generally want nothing to do with those because the math doesn’t work for them as well.

Anyway, hospital ownership notwithstanding, will the vertical-integration play work? Will this actually realign incentives and improve the value of our care? The jury is still out, but what will be key is ensuring that all this integrating doesn’t hurt competition. Because that’s what will keep companies honest. Here’s Craig Garthwaite again.

GARTHWAITE: The only way this works is if we have competition among the large, vertically integrated providers; otherwise, what you get is, if United, or Aetna, or someone ends up as the only person in the market, even if they push down costs, they’re going to capture it as profits, and they might push down costs in ways that hurt quality.

LOVE: If there are no other big competitors in the space, patients and payers will have less room to negotiate better prices or better care. They wouldn’t be able to threaten to go to another vertically integrated provider that costs less or provides more, unless there was a competitor to go to.

David Dranove agrees. He points out that we will need to preserve competition among these giant, vertically integrated systems for other reasons, too.

DRANOVE: To the extent that, say, all of the cardiologists in the market are tied up by a single system, it’s going to make it very difficult for any other system or even for a health-insurance company to try to offer a different vision of how to deliver cardiology care other than the vision of that one health system.

LOVE: Laura?

PAVIN: Jess?

LOVE: We’ve talked through so many things today.

PAVIN: We have. We’ve talked about the pros and cons of mostly, but not entirely, private healthcare models and mostly, but not entirely, public healthcare models.

LOVE: And of course we’ve talked about how hard it is to talk transparently about what these pros and cons actually are. What is prioritized and what isn’t. Who wins and who loses.

PAVIN: And throughout the series, we’ve also talked about how we got to where we are today. How hospitals, and doctors, and insurers, and drug companies, and even us patients—and a lot of historical happenstance—built us the healthcare system that America has today. Confusing. Expensive. Deeply unfair. Also dynamic, innovative, and, if you can afford it, truly world-class.

LOVE: Yeah. And so I think the natural question here is, where do we go next? Is there a way to get more value for our healthcare dollars? Because it doesn’t really seem like there’s a ready-made system out there for us to just jump to.

PAVIN: No, and that’s a good point.

It’s more likely that we’ll need to come up with multiple routes for aligning all of our misaligned incentives we’ve covered throughout these five episodes. Because as much as we need to have that big, transparent conversation as a country, the one about being willing to make trade-offs, it’s not clear if we’ll ever get to the point where we can hear each other talk and agree on which trade-offs we’re willing to make.

Like, okay, the Americans who do have decent access to the healthcare system now can get a hip replacement from a top surgeon in pretty short order, if that’s what they want. Would those Americans be willing to sacrifice that so that all Americans can finally have access to basic care? As harsh as it sounds, that’s unclear.

LOVE: Yeah. And so, until we can agree on these larger trade-offs, we’ll probably keep taking new cracks at solving our system’s problems, little by little. And luckily, that’s what our system does incentivize. It’s why we also have nontraditional, retail players taking a stab at making the economics of healthcare work.

PAVIN: Yeah, like, in 2022, Amazon acquired One Medical, which is a national network of primary-care providers.

LOVE: And then there’s what Walmart did with its Walmart Health centers and virtual care business.It created a chain of fifty-plus clinics where you could get medical appointments, dental and optical appointments, x-rays, lab work, that kind of stuff.

And it’s things like that that Dranove thinks show a lot of promise.

David DRANOVE: Will Amazon use their talents at consumer-facing product delivery, website design, and product delivery to improve the primary-care experience? Will they use their data-analytics skills to use artificial intelligence in new and creative ways? I’m excited to see new players coming into the marketplace offering new ways of delivering the healthcare products.

PAVIN: An unfortunate bit of news on this front, Amazon announced earlier this year that it was laying off a few hundred roles across One Medical and Amazon Pharmacy. Leadership wants to cut down on operating losses.

LOVE: And as for Walmart Health, also not great news. It’s closing all those clinics it opened. Not enough people paid in cash, something that Walmart thought they would do considering its discounted prices.

This may not spell the end for either of these two. But when two deep-pocketed giants can’t make the economics of healthcare work, it does make you feel a little like, “if not them, then who?”

Garthwaite doesn’t think that means our healthcare system’s future is purely a dystopian one. He thinks better leaders could be the change we need.

GARTHWAITE: Where we see new entrants fail, they are healthcare people that don’t understand business or their business people that don’t understand healthcare. And what we need is we need well trained business leaders who have a respect for the uniqueness of the healthcare market.

And I think that’s, like, success. Whoever is going to sort of lead the success and reform by U.S. healthcare is going to understand both the business and the unique aspects of healthcare.

PAVIN: As for what, exactly, this change will look like? We’ll have to see, but Garthwaite’s best guess is that it won’t be a single thing. It will be a lot of things, happening here and there, slowly taking us to a better place..

GARTHWAITE: When I was a lobbyist in DC, we would play a lot of beer-league softball, and the teams that would always win are teams that would hit singles and doubles. You got to kind of move people around the bases. People trying to hit home runs every time are going to strike out. Solving healthcare is a lot like beer-league softball. It’s going to be a bunch of solutions that one by one we knock off the problems, we move people around the bases, and we try and get to a solution. And it’s this grand idea of be it Medicare for all or be it sort of the end of megaproviders or be it vertical integration. Those are all addressing various aspects of the system that we want to think about.

[credits]

LOVE: Well! That’s a wrap on our second season of Insight Unpacked! Again, you can check out the supplementary materials for each of our episodes on our website at kell.gg/unpacked. You’ll also find season one there. That one’s on branding, and it’s really pretty fun, too. Check it out!

PAVIN: Thank you so much for listening! And if you have any questions or comments, feel free to shoot us a note at insight.kellogg.northwestern.edu.

This episode of Insight Unpacked was written by Laura Pavin and edited by Jess Love. It was produced by the Kellogg Insight team, which also includes Fred Schmalz, Abraham Kim, Maja Kos, and Blake Goble. It was mixed by Andrew Meriwether. Special thanks to Craig Garthwaite, David Dranove, Amanda Starc, Murray Ross, Conor Parker, Alexandra Salomon, and Enrico Scaffai. As a reminder, you can find us on iTunes, Spotify, or our website. If you like this show, please leave us a review or rating. That helps new listeners find us.