Featured Faculty

Alan E. Peterson Distinguished Professor of Finance; Professor of Finance

Member of the Department of Finance faculty until 2018

Yevgenia Nayberg

Unemployment insurance (UI) is the third-largest government program for transferring funds to the needy, behind only Social Security and government-sponsored health care. Though the program is sometimes criticized for reducing the motivation to find work, over the years economists have attributed a number of social benefits to it. UI provides the recently unemployed with the means to buy groceries, gas, and clothing, driving up overall consumer spending, which can be particularly helpful in a recession. It also provides job seekers with the resources to pass up less desirable opportunities while hunting for the right position.

Recent research by a team that included two Kellogg School of Management professors suggests that UI’s social benefits extend much further than previously believed. The expansion of UI “played an important role in preventing foreclosures during the Great Recession,” says Brian Melzer, an assistant professor of finance. Melzer and David Matsa, an associate professor of finance, collaborated on the study with Joanne Hsu of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors in Washington, D.C.

The researchers estimate that between 2008 and 2012, the program helped to avert $70 billion in social costs from foreclosures, including depreciation in the foreclosed properties’ structural values, decline in neighboring home values, and transaction costs paid by lenders and households. In addition, the expansion improved access to credit for a broad swath of poor individuals, including people who never had to draw on the insurance. In a broader sense, the study argues for the effectiveness of public policies like unemployment insurance that improve people’s ability to pay off their debts, as opposed to merely improving their incentive to pay them off.

Income Risk and Default

The research project started with the intuitive feeling that, as Melzer explains, “reducing household income risk would reduce default.” However, he continues, “it was uncertain how big the effect would be.” When the research began, nobody had yet investigated the link between mortgage default and workers’ job histories. Making that connection enabled the researchers to provide new insights.

To determine the extent of the relationship between income risk and default, the researchers used the fact that the level of unemployment insurance varies among states. In the basic program, unemployed individuals can receive half of their income for up to six months if they haven’t found a job. But the weekly benefit is subject to a cap. As a result, the total benefits currently available range from $6,000 in Mississippi to $28,000 in Massachusetts. In response to the Great Recession, the federal government helped states offer extra payments, with amounts dependent in part on those states’ unemployment rates. The government provided extra funding that increased the duration of UI—for example, in the time period the researchers studied, recipients qualified for 20 additional weeks of benefits totaling up to $6,000 in South Dakota but 53 additional weeks of benefits worth up to $31,000 in New Jersey. The researchers then tracked mortgage delinquency trends for employed and unemployed households between 1991 and 2011, matching them to these differences across states.

Implications for Housing Policy

The results show a significant correlation between UI and improved financial circumstances for individuals. The impact on housing proves surprisingly large. An increase of $3,600 in a state’s maximum regular UI benefits prevents 15% of the average mortgage delinquencies caused by layoffs. Over the long term, that serves to reduce foreclosures among unemployed homeowners. “These effects are sizable,” the team writes. “[T]he increase in evictions, a subset of defaults, associated with being laid off is cut almost in half.”

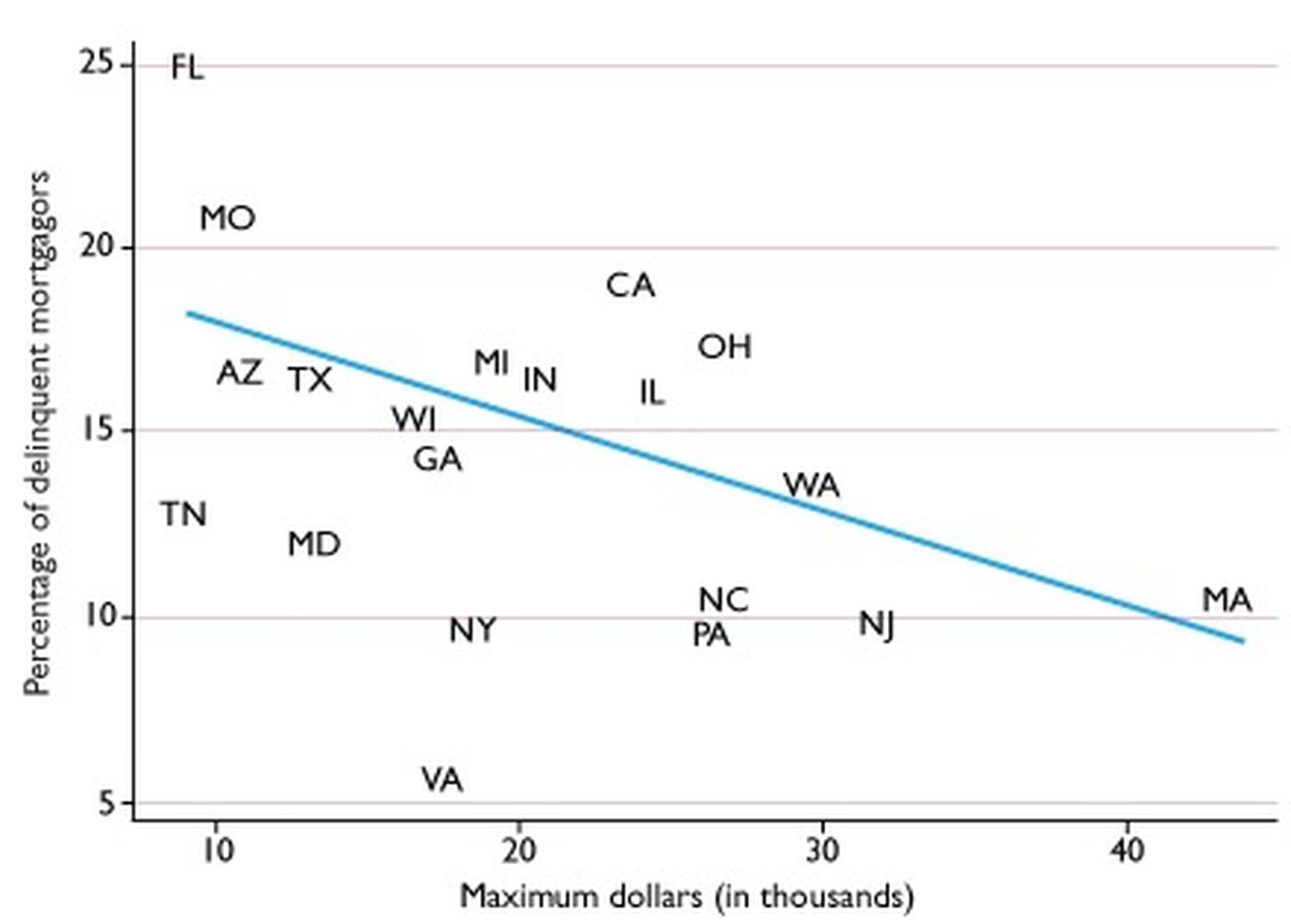

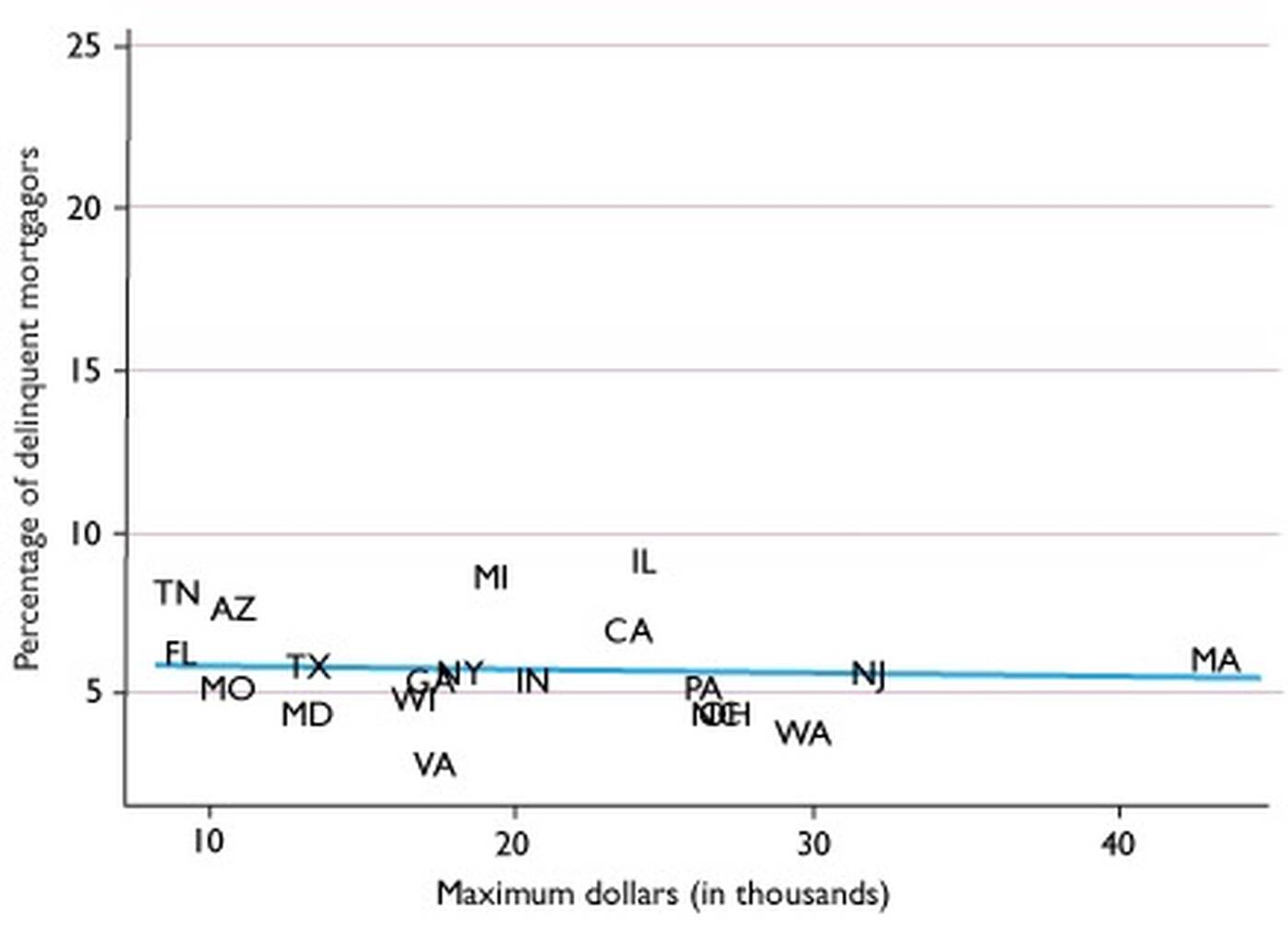

[The figures below show the relationship between the maximum amount of extended UI benefits a household is eligible to receive in a given state and the percentage of delinquent mortgagors in that state (as of May 2009). As maximum UI increases, delinquent mortgages decrease—but only among households that experienced unemployment.]

Households Experiencing Unemployment

Households Experiencing No Unemployment

The impact applies even to mortgage holders who owed significantly more than the value of their houses. “A policy like UI that improves a household’s ability to repay debt is effective even for households deeply in debt and underwater on their mortgages,” Melzer says. That is,even the households with the greatest incentive to strategically default are more likely to stay in their homes.

Intriguingly, UI provides mortgage relief more effectively than programs dedicated to that goal, such as the Home Affordable Refinance Program and the Home Affordable Modification Program. It does so, the team explains, by transferring money directly to homeowners, bypassing lenders and loan services. “We’re not saying that UI is the perfect policy to prevent mortgage foreclosures. Half of UI recipients rent or have no mortgage. But the effect—avoiding 1.4 million foreclosures—is too big to be ignored,” Matsa says.

In addition to the social benefits of avoiding the foreclosures, these effects also reduced the cost of providing UI to households in need. That’s because the federal government effectively guarantees many mortgage payments through Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, allowing money saved by preventing foreclosures to essentially offset some of the money spent on UI. “We estimate that avoiding foreclosures reduced the cost of extending UI during the Great Recession by about 20 percent,” Matsa says.

Beyond Housing

But the benefits of UI are not restricted to the unemployed—or for that matter, their neighbors, communities, and lenders. By reducing the likelihood that unemployed borrowers would default, unemployment insurance has an additional consequence: It improves the creditworthiness of individuals at risk of being laid off.

By analyzing mortgages, home equity lines of credit, and credit card loans, the researchers were able to determine that households—even those experiencing no loss of employment—enjoy expanded access to credit, including lower interest rates and higher credit limits. Overall, interest rates decline by 1.4 percent and credit limits jump by $1,700 for every $3,600 increase in maximum UI benefits. For households earning less $35,000 a year, the decrease in interest rates and increase in credit limits are substantially greater.

The study suggests that, despite the costs of implementing and expanding UI, the program provides even broader societal value than previously understood. Policy makers should keep these benefits in mind as they consider programs that offer direct financial assistance to individuals looking to get back in the black. “Because costs spill over from housing default, our findings show that UI benefits the neighbors of the unemployed and the financial system overall,” Melzer says. “You don’t have to lose your job to benefit from unemployment insurance,” Matsa adds. “People often benefit from social insurance even if they never draw a payment.”

Joanne W. Hsu, David A. Matsa, and Brian T. Melzer, “Positive Externalities of Social Insurance: Unemployment Insurance and Consumer Credit,” Working paper, July 2014.