Innovation Leadership Economics Jun 1, 2020

Want Your Employees to Innovate? Trust Them.

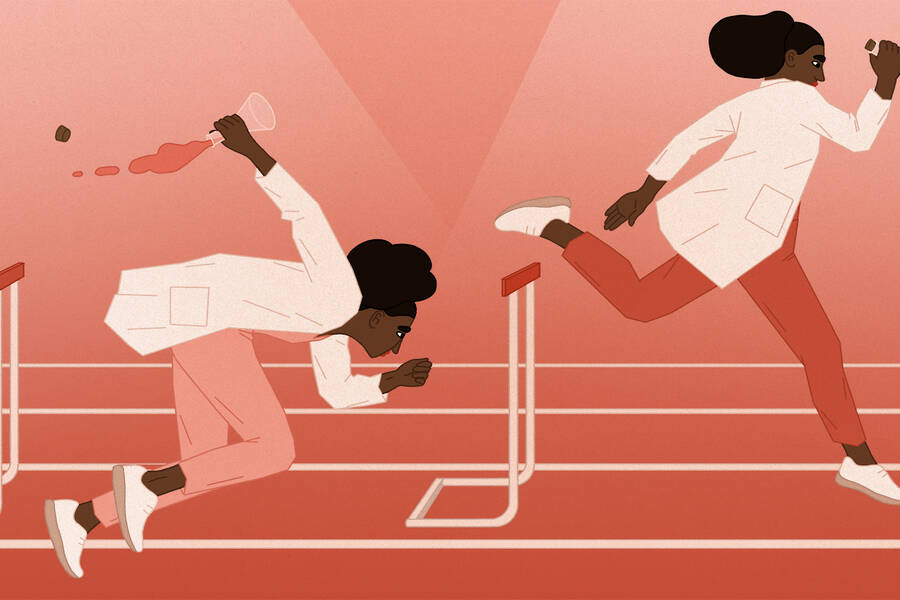

R&D teams take more risks—and do better work—when their CEOs have faith in them.

Michael Meier

Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos extolled the virtues of failure in his annual letter to shareholders in 2016.

In the letter, he referred to failure and innovation as “inseparable twins,” adding: “Most large organizations embrace the idea of invention, but are not willing to suffer the string of failed experiments necessary to get there.”

So how can leaders make those failed experiments feel more palatable? In other words, how can they make sure that employees feel safe to pursue risky outside-the-box ideas—and then, when those ideas don’t pan out, to try again?

Recent research from Kieu-Trang Nguyen, assistant professor in Northwestern’s Department of Strategy, highlights one part of the answer: by ensuring that those at the very top of the org chart trust their employees.

Nguyen finds that when a firm replaces its CEO with one who’s likely to be more trusting, the firm produces more patents. What’s more, the individual researchers considered most trustworthy by the CEO turn out higher-quality patents than those whom the chief executive trusts less, suggesting that researchers use this trust as a license to take more dramatic risks in the pursuit of innovation.

The findings have a clear upshot: leaders who urge employees to “embrace failure, make mistakes, and learn from those mistakes,” as Nguyen puts it, will position their companies to innovate more and better. And they can reap the financial benefits of doing so.

However, she warns, trust can backfire when those on the receiving end are undeserving. “Trust is not a silver bullet,” she says.

Measuring Trust in the Workplace

Nguyen’s study builds on a body of research that looks at a different aspect of trust. These studies show that countries with more trusting cultures tend to enjoy stronger macroeconomic growth than those with less trusting cultures, partly by fostering more innovation.

For example, some studies show a cross-country correlation between trust and expenditures on research and development (R&D). That made Nguyen think that trust could likely drive innovation—and, thus, growth—in individual firms as well.

To test this theory, Nguyen chose to focus on individual CEOs’ attitudes toward trust. After all, a top boss’s perspective and personality tend to influence the entire company.

But how could Nguyen ascertain how trusting CEOs were? A direct method—like determining personal attitudes one by one—simply wasn’t practical.

However, there was another, less direct way to get at trust. A large body of research showed that cultural inheritance helps shape certain beliefs and attributes, including trust. In the U.S., specifically, individuals have been shown to display levels of trust and other values that strongly correlate with those in the home countries of their ancestors, even when they are several generations removed from those countries. This allowed her to infer, on average, how trusting a given CEO was likely to be based on average trust levels in the CEO’s ethnic group.

“Failure happens, and a more trusting CEO is more likely to attribute failure to bad luck.”

Nguyen used data from the U.S. General Social Survey, focusing on a question that measured attitudes toward trust (“Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted?”). The survey also asked respondents about their ethnic origin (“From what countries or part of the world did your ancestors come?”), meaning that Nguyen was able to determine the average trust level of each of the 36 ethnic origins most common in the U.S.

The survey revealed that trust levels varied dramatically, even among ethnic groups with roots in the same geographic region. For instance, while Swedish-Americans were among the most trusting groups (63 percent said they could trust people), Greek-Americans were among the least trusting (47 percent). (Nguyen emphasizes that these are merely averages for the entire ethnic group; it is entirely possible that certain Greek-Americans are more trusting than certain Swedish-Americans.)

Nguyen used the last names of the 5,753 CEOs in her sample to ascertain their ethnic origins, using an algorithm derived from Census data. She then assigned each CEO the trust score that corresponded to that ethnicity.

Before conducting her main analysis, Nguyen did a final check. Could a CEO’s last name really predict the trust level across her organization? Nguyen used text analyses conducted by MIT researchers of almost one million online employee reviews to glean company-wide trust attitudes at 500 large U.S. public firms. The evidence confirmed that when a more trusting CEO (as measured by last name) took over, firm-wide trust seemed to increase.

Trusting Employees Drives Innovation

To observe the effect of CEO trust on innovation, Nguyen again zeroed in on moments of turnover: When a new CEO was more trusting than her predecessor, did the firm produce more patents?

Nguyen found that hiring a more trusting CEO does indeed stimulate more innovation within a firm. Increasing CEO trust by 11 percentage points, for instance—comparable to moving from a Greek-American to an English-American CEO—corresponds with a 6.3 percent increase in patents filed.

For the average firm, this is about 1 additional patent per year, equivalent to roughly $3 million in additional value for the firm.

However, it was possible that more-trusting CEOs enjoyed higher patent numbers for reasons that had little to do with trust—for instance, perhaps they oversaw especially effective financial-incentive programs or simply valued patent output more than less trusting leaders. So, to confirm that trust was, indeed, driving innovation, Nguyen also tested whether researchers who enjoyed more trust from the same CEO proved more innovative than their peers in the same firm.

To quantify trust in individual CEO–researcher relationships, she found a measure for bilateral trust that was, again, based on ethnic origin: the Eurobarometer is a series of surveys in which respondents from 16 European countries were asked whether they have “a lot of trust, some trust, not very much trust, or no trust at all” in people from 28 other countries. (For example, a British person would be asked how much they trust Germans, how much they trust Italians, and so on.)

Then, much like before, she used last names of CEOs and researchers, and the locations of the company’s overseas R&D labs, to estimate how much the CEO was likely to trust her research team. (For instance, she could quantify how much an Austrian-origin CEO was likely to trust his R&D lab in France, or how much an Italian-origin CEO might trust his mostly German software engineers.)

She found that when these individual researchers were highly trusted, they tended to produce more patents.

“When trust is misplaced, a CEO becomes less effective in screening out the [workers] who are not doing the work.”

What’s more, under a more trusting CEO, higher-quality patents (as measured by the number of citations they eventually received) increased more than low-quality ones. While low-quality patents tend to mark a less-risky, marginal invention, high-quality ones are likely to accompany a groundbreaking discovery—the kind that is typically only hashed out over long periods of trial and error. This pinpointed the likely channel through which trust emboldens innovation in firms: by establishing an environment where it’s safe to take the sorts of risks that can yield an important new invention.

“Failure happens, and a more trusting CEO is more likely to attribute failure to bad luck and allow the researcher to stay at the firm and take a second chance,” Nguyen says.

The Importance of Building Trust—and How It Can Backfire

While these findings suggest that trust can be valuable for spurring innovation, corporate leaders shouldn’t go too far, Nguyen says.

“When trust is misplaced, a CEO becomes less effective in screening out the ones who are not doing the work,” she explains. “The trust effect of the CEO is strongest when the firm has a better-quality researcher pool.” In other words, allowing hard-working researchers to take big risks is good for the company’s bottom line—but giving second and third chances to unmotivated or unskilled researchers is not. So if employees are shirking, more trust isn’t likely to change anything.

And importantly, Nguyen only evaluated the impact of trust on innovation. As such, it is possible that increased trust has negative effects on dimensions she did not study. Still, she argues, encouraging the right level of trust is likely crucial in many industries—something the best CEOs already accept as true.

Another takeaway that Nguyen emphasizes: corporate culture of trust can indeed be built from the top down, even within just a few years of a new leader taking the helm.

“We know that culture is hard to change,” she says. “So I was surprised to see quite a large effect, which means that firms’ organizational cultures change faster than I initially thought. Top leaders seem to have a larger impact than I expected.”