Featured Faculty

John L. Ward Clinical Professor in Family Enterprise; Executive Director of the John L. Ward Center for Family Enterprises

Michael Meier

Family-owned businesses that have survived to the third generation and beyond are often characterized as risk-adverse capital preservers. Once wealth has been amassed, after all, there can be a natural tendency to protect rather than grow it.

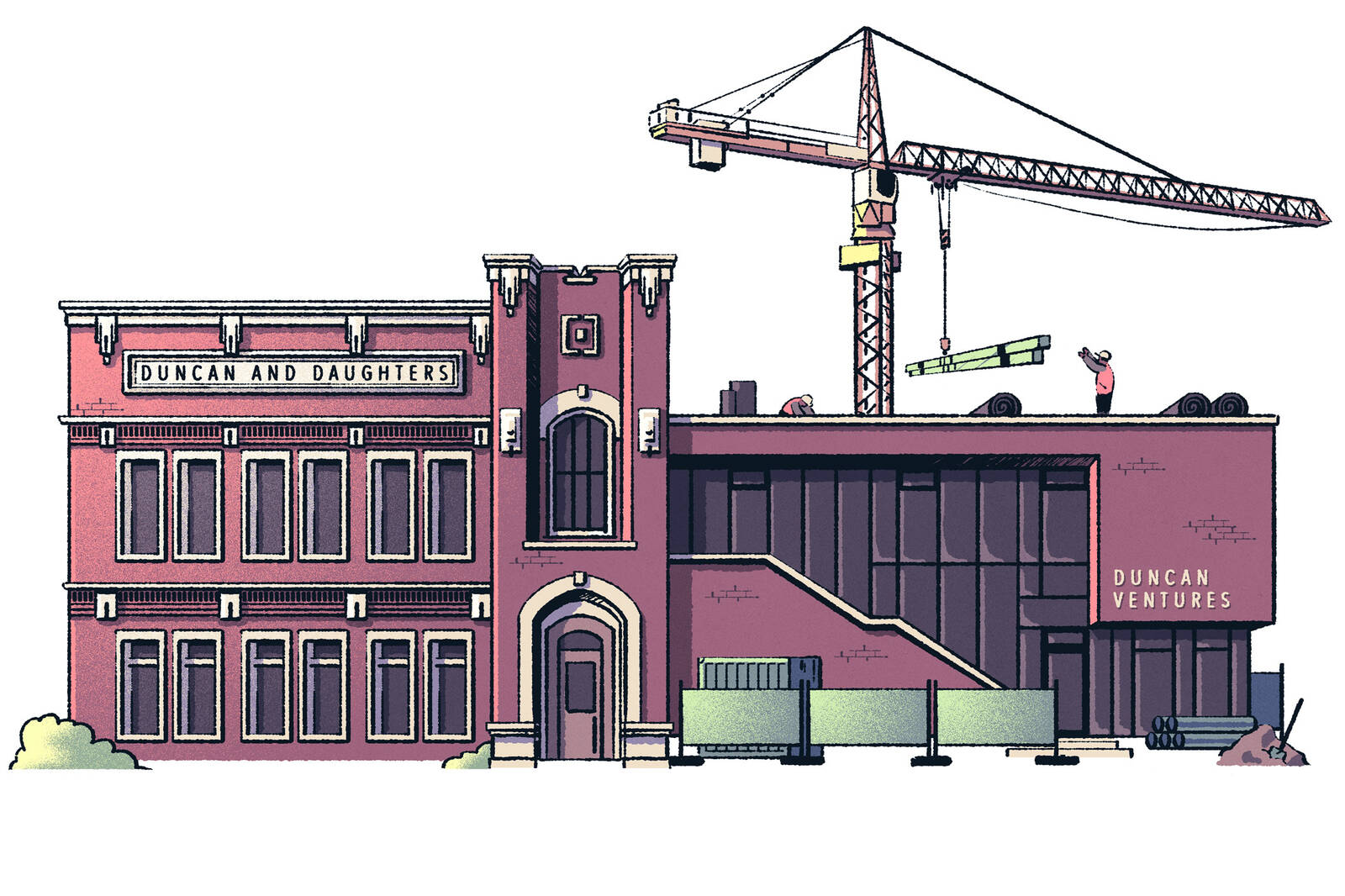

Yet, in our experience working with later-stage business families at the John L. Ward Center for Family Enterprises, we are seeing something relatively new: family businesses creating venture-investing subsidiaries.

So why are families moving away from a wealth-preservation model to one that is far riskier—an industry in which just 25 percent of venture-backed firms can expect to succeed? And just as importantly, what does it take for family enterprises to do venture investing well?

For many family owners, part of the value proposition in venture investing is the opportunity to stay ahead of the competition. Families that want to remain in business for generations to come are thinking about how to be the disruptors instead of the disrupted.

John Thacher is a third-generation owner and board chair of the agricultural giant Wilbur-Ellis, which recently created a venture unit, Cavallo Ventures. In his view, venture investing offers a way to mitigate risk to the family’s core operating business. “We want to get under the covers to see what technologies are coming our way, and what level of disruption will accompany them,” he says. Only then can they adapt accordingly.

John Tracy, board chairman and CEO of Dot Family Holdings, maintains that Dot takes a similar view. The Tracy family, whose parents co-founded Dot Foods, recently purchased control over two early stage tech companies. They concluded that the startups were better positioned than internal teams to innovate quickly to solve some of the problems facing the core business. Some opportunities “require solutions that we can’t move fast enough on ourselves,” he says.

Creating a venture-investing subsidiary is a process—one that may look different over time as family owners learn what works for them and what doesn’t.

— Jennifer Pendergast

Investing can also mitigate against another kind of risk: family risk. Venture investing offers emerging leaders an opportunity to strike out on their own to create something new, rather than restricting them to a traditional management path in their family enterprise. This is something that is increasingly prized by younger generations. Take Enrique M. Zambrano, partner at Proeza Ventures, venture unit of Grupo Proeza, the 65-year-old Mexico-based family conglomerate. He returned to his family business after earning his undergrad and MBA degrees from Stanford, launching his own e-commerce company and gaining experience as an angel investor. While he also had experience working at Metalsa, one of Proeza’s businesses, he is more passionate about venture investing, and was simply more attracted to the opportunity of investing in the future of mobility through Proeza Ventures.

Beyond mitigating risk, venture investing lets family businesses play to a big strength: deal flow, or finding the appropriate companies or technologies in which to invest.

This is usually one of the biggest disadvantages for new entrants into venture investing. But family businesses that are established, well-respected players in an industry are often approached with deals. Being able to offer long-term, committed capital with a strong reputation in the marketplace can be appealing for those seeking investment.

This is something Paul Darley ’03 MBA—CEO, chairman, and third-generation owner of W.S. Darley and Company—has experienced. The company, a 100-year-old provider of fire, safety, and defense equipment, is routinely approached by startups seeking distribution of their products. Of particular note is their trade-show booths: given the company’s long history in the industry, their seal of approval helps new technologies gain credibility. And showcasing the tech at trade shows in turn gives Darley a sense of the possible market for it—good information as it decides whether to ultimately invest. The firm recently invested, for instance, in Ascent Integrated Tech, a startup that has developed a technology for locating firefighters.

However, access to deals doesn’t translate into success unless the organization can appropriately vet opportunities and bet on the winning ones. So how are families accomplishing this?

For one, a talented team is needed. But Thacher, of Cavallo Ventures, cautions against populating this team with leaders from operating units from the family’s core business. This new team will need to act at a different pace and risk level. And it should ideally be led by someone with both a passion for venture investing and knowledge about the family’s core business, so that the team can identify investments that add value to these core operations. This leader will also serve as a translator or bridge between the venture team and operational leaders.

Attracting the right venture team might require family owners to tweak how they structure compensation. Many family owners balk at the high salaries and co-investment opportunities that other funds offer—but internal venture funds can’t attract talent if they are significantly below market. To be competitive, owners will need to recognize that venture investing is a completely different business, with different expectations.

Finally, family owners will need to understand that creating a venture-investing subsidiary is a process—one that may look different over time as family owners learn what works for them and what doesn’t. So staying open-minded is useful.

About six years ago, when Grupo Proeza decided to revamp its innovation practices, one of its first initiatives was to launch the MLAB, a company builder (also known as a venture lab) that leveraged the capabilities of Metalsa, a supplier of structural components for the automotive market. But a few years after launching this, the Proeza Board decided this strategy was too capital intensive, too risky, and simply not a fit for the group. So they turned to venture investing as a way of accomplishing the same goals, but through an approach with which they had more familiarity. This led to the launch of Proeza Ventures, a mobility-focused venture-capital fund, that operates mostly as a traditional VC fund, looking for financial returns over strategic ones. The thinking was that focusing on financial returns would make it a better long-term asset for the group.

For Grupo Proeza, some strategic benefits have nonetheless come—from unexpected places. “Our legacy operations do not have a history of focusing on marketing, which has been low-key throughout its history,” says Zambrano. “Proeza Ventures has positioned Proeza as an innovative group investing in the future.”