Featured Faculty

Professor of Management and Organizations; Management and Organizations Department Chair

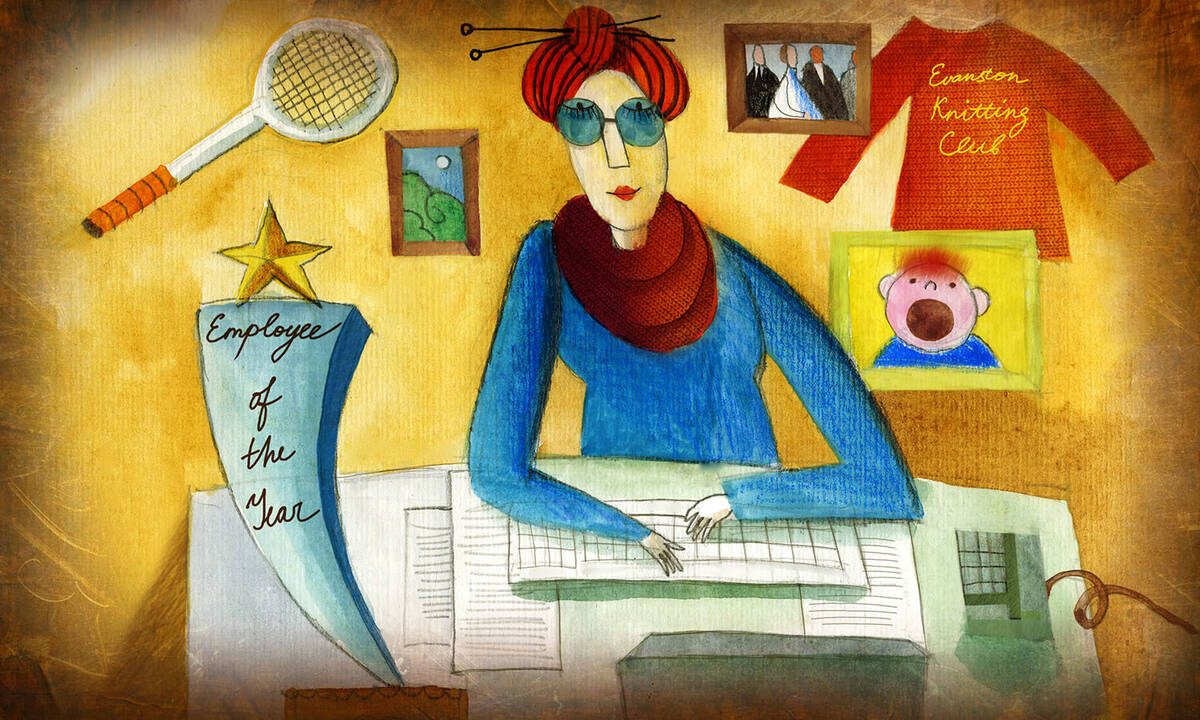

Yevgenia Nayberg

Which employee would you rather have on your team: one who embodies The Bard’s maxim—“to thine own self be true”—or one who hews closer to Michael Corleone’s credo that “it’s not personal; it’s strictly business”?

According to new research from Kellogg’s Maryam Kouchaki (which quotes both Shakespeare and The Godfather), employees are more likely to engage in bad behavior if they compartmentalize their personal and business lives.

When people separate their work identities from who they are at home and among friends, the separation can lead them to feel inauthentic, which increases the risk of unethical behavior, explains Kouchaki, an associate professor of management and organizations.

In a series of experiments and a field study, Kouchaki and colleagues show that people who integrate their different identities into one consistent sense of self feel more authentic and are therefore less likely to engage in immoral behavior than those who fail to knit together their various selves.

“We each have multiple identities that can manifest at any time,” says Kouchaki, who conducted the research with Mahdi Ebrahimi of California State University, Fullerton and Vanessa Patrick of the University of Houston. “When those identities are integrated through shared meaning, there’s a sense of cohesiveness, which leads to greater feelings of authenticity and better moral behavior.”

But when they’re segmented, she says, “we feel in conflict, which creates a sense of inauthenticity and increased risk of unethical behavior.”

In this study, Kouchaki and her colleagues focused on authenticity and identity integration. Specifically, they wanted to establish a link between a person’s identity integration and feelings of inauthenticity leading to dishonest behavior. They undertook four studies to see if this was the case.

When people’s identities are poorly integrated across multiple identities, they report feeling inauthentic and they behave unethically.

They first established a link between poorly integrated identities—say, a manager at work, a competitive cyclist at the gym, and a mother in the evening—and feeling fake.

Nearly 300 working adults were randomly assigned to read and respond to statements that were designed to prompt feelings of either low or high identity integration. They were told that every person has multiple selves or identities and that as a typical professional, they have two major identities: their professional identity and their nonprofessional identity, such as who they are at home.

Then participants were prompted to think and write about how these two identities were either segmented and incompatible, or were integrated and compatible. Then they reacted to a series of statements designed to measure feelings of inauthenticity—such as “I am unsure of what my ‘real’ feelings are” and “I don’t feel I can be myself”—on a seven-point scale.

As predicted, participants who were exposed to low-identity-integration statements about how their different selves were incompatible reported greater feelings of inauthenticity than those who responded to high-integration prompts about compatible identities.

Next, the researchers sought to show that when people’s identities are poorly integrated, they are more likely to engage in unethical behavior.

They again prompted participants to feel that their identities were either well-integrated or poorly integrated, and then had them play an online coin-toss game. Each player took ten turns predicting the outcome of the coin toss before they gave the virtual coin a flip. Participants were instructed to honestly report the accuracy of their predictions and received money for each correct prediction.

The researchers found that participants who were exposed to the low-integration statements cheated significantly more than both those who were exposed to the high-integration statement and a control group that had not been exposed to statements about identity integration.

So when people’s identities are poorly integrated across multiple identities, they report feeling inauthentic and they behave unethically. But are these feelings of inauthenticity why they behave unethically?

In another study, researchers again prompted 144 college students to feel that their identities were more or less integrated, and again asked them to respond to a series of questions to measure authenticity such as “Right now, I feel as if I don’t know myself very well.”

The researchers then presented the students with eight scenarios of unethical behavior, such as cheating on a school project, and asked how likely they would be to participate. Again, they found reliable links between low identity integration and both feeling fake and increased bad behavior. Critically, however, the researchers were able to statistically confirm that inauthenticity was the factor that underpinned the relationship between low identity integration and dishonest behavior.

Finally, the researchers wanted to confirm that this relationship between inauthenticity and dishonesty existed in actual workplaces, and not just the laboratory. So they recruited 150 pairs of real-life bosses and underlings from a variety of organizations.

The subordinates reported the level of their identity integration and their general feelings of authenticity at work. The supervisors, meanwhile, recorded the extent to which the employee engaged in various bad behaviors, such as falsifying an expense report or being rude to someone at the office.

Once again, the researchers found a significant correlation between workers’ low identity integration and their bosses’ reports of organizational and interpersonal dishonesty.

The survey responses indicated that those workers with low identity integration reported feeling more inauthentic and were judged by their supervisors as more likely to cheat or engage in other unethical behavior.

At the extreme, unethical behavior can lead to corporate scandals that take a significant financial and reputational toll on organizations. But even less extreme misbehavior can contribute to a negative culture and increase the likelihood of additional misbehavior.

Kouchaki says companies should therefore try to help employees integrate their work and other identities, which in turn will foster ethical behavior. This could be done via a range of different initiatives, from casual Fridays where employees can dress more to their own liking, to corporate retreats that encourage frank emotional discussion.

Understanding the connection between feeling phony and a propensity toward dishonesty also adds another layer of context to an idea championed by Sheryl Sandberg and other Silicon Valley leaders: the right of employees to bring their “whole selves” to work.

“We haven’t provided evidence that bringing your whole self to work is an unabashedly good idea—there could certainly be unintended consequences,” Kouchaki says. “But we have demonstrated that it’s in an organization’s interest to help people feel more control over and cohesion in their identity.”