Leadership Organizations Feb 3, 2017

Are Your Employees Putting the Company’s Interests First?

A new tool measures a firm’s “stewardship climate.”

Will Dinski

Boy Scouts know to leave a campground in better shape than they found it. Do employees show the same regard for their firms?

Leaders should put the interests of their firms above their own—such is a tenant of “stewardship theory.” And it is easy to see why companies would want to encourage such a mindset from their employees.

But how do you steer your company toward a climate of stewardship?

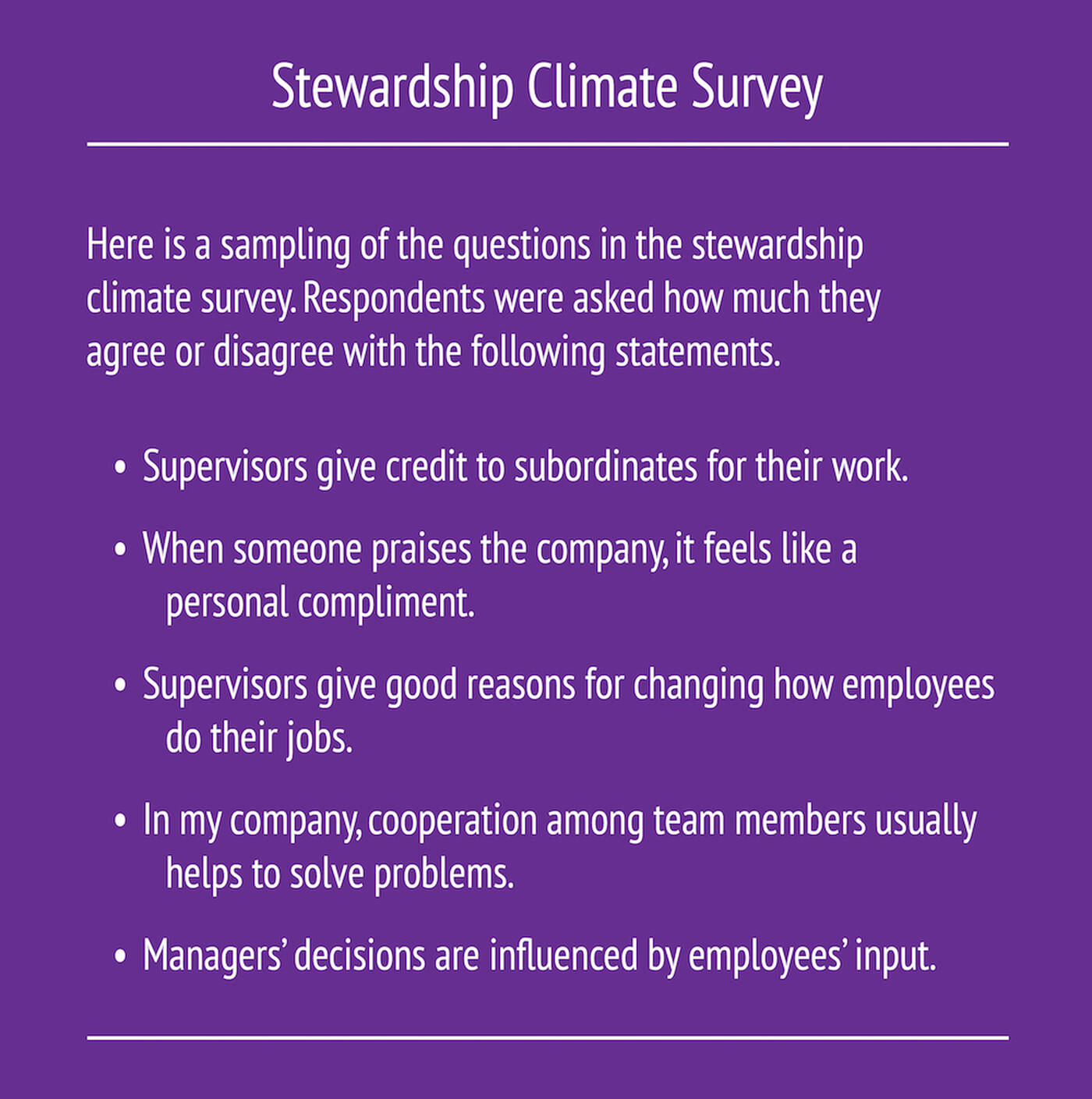

The first step is to be able to measure stewardship, says Justin Craig, codirector of the Center for Family Enterprises at the Kellogg School. But no tool existed. So he and coauthors created an 18-question survey to help leaders gauge their companies’ stewardship climate.

“Everybody started to buy into stewardship, the concept, but nobody had actually gone out and rigorously tested the conceptual argument,” Craig says.

With statements like, “When someone praises the company, it feels like a personal compliment,” and “Managers make employees feel like they work with them, not for them,” Craig gives leaders a tool to assess their firms, start conversations with employees and potential hires, and evaluate their own goals.

Craig then used the survey to compare the stewardship climates at family- and nonfamily-run businesses.

Measuring Stewardship Climate

In a climate of stewardship, employees are intrinsically motivated by a desire to do good work.

“They are contributing to something,” says Craig, who is also a clinical professor of family enterprise. “They see the company as an extension of themselves.”

“It’s not flaky. It’s not an airport book. It’s theory-driven and evidence-based.”

And leaders lead not by simply flexing their muscles and displaying power.

“The manager is involved because they want to be, not because they have to be,” Craig says. “They’re not saying you do this because I’m the boss and you’re the employee. They don’t behave like that.”

In short, “it’s nirvana,” Craig says.

Yet despite its obvious appeal, stewardship theory remained just a theory for more than two decades until Craig’s research.

Craig was intrigued by the idea that no one had taken the theory out for a test drive to see if it could quantifiably hold up in the real world. Some researchers had tried to use proxies for stewardship, such as the amount CEOs pay themselves compared with their employees, but no one had tried to measure stewardship directly.

And so Craig’s idea for a stewardship climate scale was born.

The survey evaluates both the stewardship levels of individuals and of the overall organization in order to provide an understanding of the overarching climate within a company.

Craig teamed up with Clay Dibrell at the University of Mississippi, Don Neubaum at Florida Atlantic University, and Chris Thomas at Saint Louis University. They administered a first round of the survey to more than 200 people at nearly 90 organizations. They then analyzed the responses to make sure that the level of stewardship climate looked consistent across employees who worked at the same firm.

Once they established the reliability of the scale, they administered the final 18 questions again to nearly 400 people at nearly 150 organizations—some of which were family-run and others which were not. They again confirmed that people within the same organization ranked the stewardship climate similarly.

Stewardship in Family Firms

Once they were confident that the survey reliably measured stewardship climate, they further reviewed their data.

The researchers found that, as anticipated, family firms have a stronger stewardship climate than nonfamily firms.

Moreover, in family firms—but not nonfamily firms—there is a link between stewardship and the level of innovation, with increasing innovativeness associated with stronger financial performance.

Taken together, this means that family firms with a strong stewardship climate get a performance boost due to the higher level of innovation there. This, Craig says, confirms the importance of stewardship.

“Why does it matter that we have a stewardship climate? Is it just touchy-feely?” Craig says. “We have established that it matters because it improves firm performance, in this case through innovativeness.”

Practical Applications for Stewardship Scale

Craig sees the value of the stewardship scale going far beyond these measures, however. The 18 questions can act as a conversation starter—a way to talk with employees to gauge their work experience or nudge them toward better performance. A manager might modify the questions to make them suitable for job interviews.

Or the scale could act as a prompt for self-reflection, Craig says. Executives could use it to think through their own roles and to make managerial changes that would encourage employees at all levels to become better stewards.

Thinking through these questions can offer real value to an organization. “It’s not flaky. It’s not an airport book,” Craig says. “It’s theory-driven and evidence-based.”

Craig said a Kellogg alumni recently praised the study after hearing Craig speak about his research. According to Craig, “this tool will be useful for me to refine our performance review process.”