Finance & Accounting Jan 5, 2021

Employment Plunged to Great Depression Levels in 2020. What’s Ahead in 2021?

Even with vaccine rollouts and a new stimulus bill, the U.S. economy faces a daunting challenge.

Lisa Röper

The year 2020 may be in the rearview mirror, but much of the economic uncertainty that characterized it is still with us. While the U.S. economy appeared on the brink of recovery in October, the virus surge of November and December dimmed the prospects for a strong rebound in early 2021.

“Despite the COVID spike, there are those who are still optimistic about the economy,” says Phillip Braun, an economist by training and a clinical professor of finance at the Kellogg School. “I’m less so.”

Even the approval and rollout of COVID vaccines and a $900 billion stimulus package in December will only go so far in boosting the recovery.

“It’s going to take time for the pieces of the puzzle of the economy to fit back together again,” says Braun. “It’s not like one day we wake up and the vaccine’s widespread and people are employed and they’re spending. It has to put itself together before it jumpstarts.”

And one of the factors most central to the nation’s economic recovery is job growth, says Braun. He offers his employment predictions for the year ahead.

Recovery and Stall

After the initial round of pandemic shutdowns, employment in the U.S. plunged to rates not seen since the Great Depression. Then, throughout the summer and into the fall of 2020, the country saw a steady climb in people returning to work—a climb that pleasantly surprised some economists.

But a surge in cases, coupled with new restrictions around the country, stalled the economic momentum. New unemployment claims trended up again in December.

“That’s a negative signal about the employment situation,” Braun says. “My expectation is that unemployment is going to deteriorate in the first and second quarters of 2021 because of the current pandemic spike.”

Moreover, with about 35 percent of jobless workers having been out of work for more than six months, and millions more leaving the workforce entirely, the employment situation may already be worse than the unemployment rate indicates.

One piece of good news? Catastrophe has been averted, at least for now.

The scheduled end of extended unemployment benefits from the March 2020 CARES Act was seen as a cliff for roughly 12 million people facing longer-term unemployment. But an 11-week extension written into the $900 billion December stimulus package—as well as a $300 weekly bonus to unemployment checks—will provide some temporary relief. This may not rescue families currently facing unemployment, but it will have other positive effects.

“It’s going to keep consumer spending afloat,” Braun says. “So it’ll minimize the negative impacts of unemployment on economic growth. It’ll help stabilize the number of families that enter poverty, though it may not make those numbers better.”

But Braun cautions that the unemployment-insurance extension is unlikely to be sufficient. “Even as the vaccine rolls out, I can’t think of any one sector of the economy that is going to really rebound quickly,” he says.

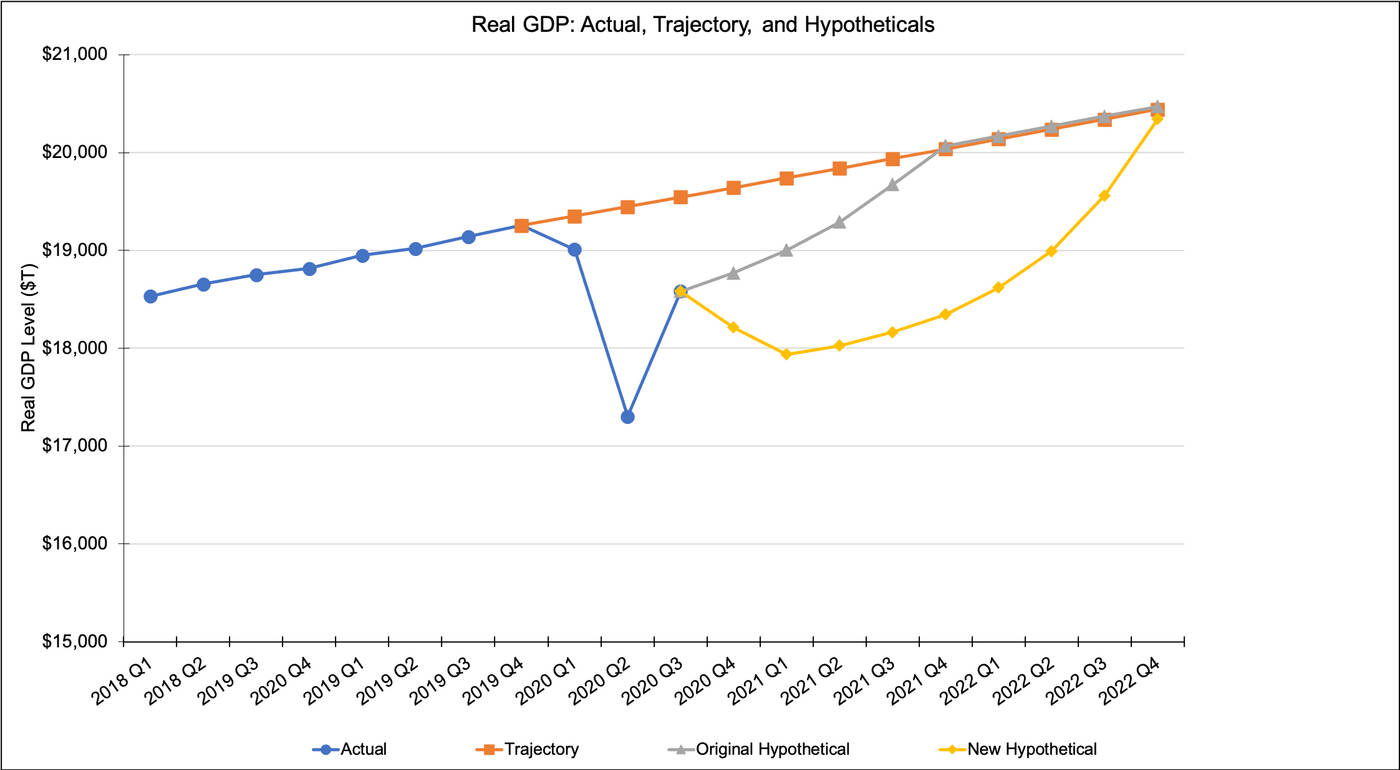

In the graph below, he plots out possible trajectories for the U.S.’s gross domestic product (GDP), each reflecting different hypothetical scenarios: one where COVID never happened, one where life returned to normal after the initial surge, and one that takes into account the second surge in cases. He estimates that the U.S. will be making up lost ground well into 2022.

Eventual Recoveries

Braun points to a few outstanding questions that may ultimately determine job growth over the coming years.

The first centers on funding to states and municipalities. One of the shortcomings of the latest package is that it doesn’t provide state and local governments with any funding. Braun worries that this will magnify the economic toll on certain industries and their workers.

“Many states have pushed their budgets to the limit. That lack of funding is going to dramatically reduce what they are going to be able to do, unfortunately,” he says.

That’s because states now have zero wiggle room to provide support for small businesses—and in fact may have to reduce their own contracts and spending, cutting off an otherwise reliable source of revenue for their communities.

“Even with federal grants and loans to small businesses, we’re going to see a lot of restaurants and gyms and family-owned businesses start to go bankrupt,” he says.

The second question is, even if businesses do regain their health, how many jobs will actually return?

Braun is worried that many of the jobs companies cut in the first wave of the pandemic were done so to increase efficiency. These jobs likely are not coming back, so even if the picture begins to brighten in the latter half of the year, the pandemic will leave a long-term mark on the workforce.

“These companies are going to be looking to robots and other ways to produce their products,” he says. “After all this is over, there’s going to be a higher level of unemployment simply because companies used this process to become more efficient.”