Featured Faculty

Henry Bullock Professor of Finance & Real Estate; Director of the Crown Family Israel Center for Innovation; Co-Director of the Guthrie Center for Real Estate Research

Riley Mann

In the early 1900s, U.S. corporations raised money largely by issuing secured debt. This form of debt requires borrowers to offer the lender assets as collateral, which in turn makes the lender more willing to give borrowers a low interest rate. Secured debt thus seems like a win–win.

Over the past century, however, U.S. corporations have made a marked shift away from secured debt, preferring unsecured debt (or loans not backed by collateral) instead, according to research by Efraim Benmelech, a professor of finance at the Kellogg School, Raghuram Rajan of Chicago Booth, and Nitish Kumar of the University of Florida.

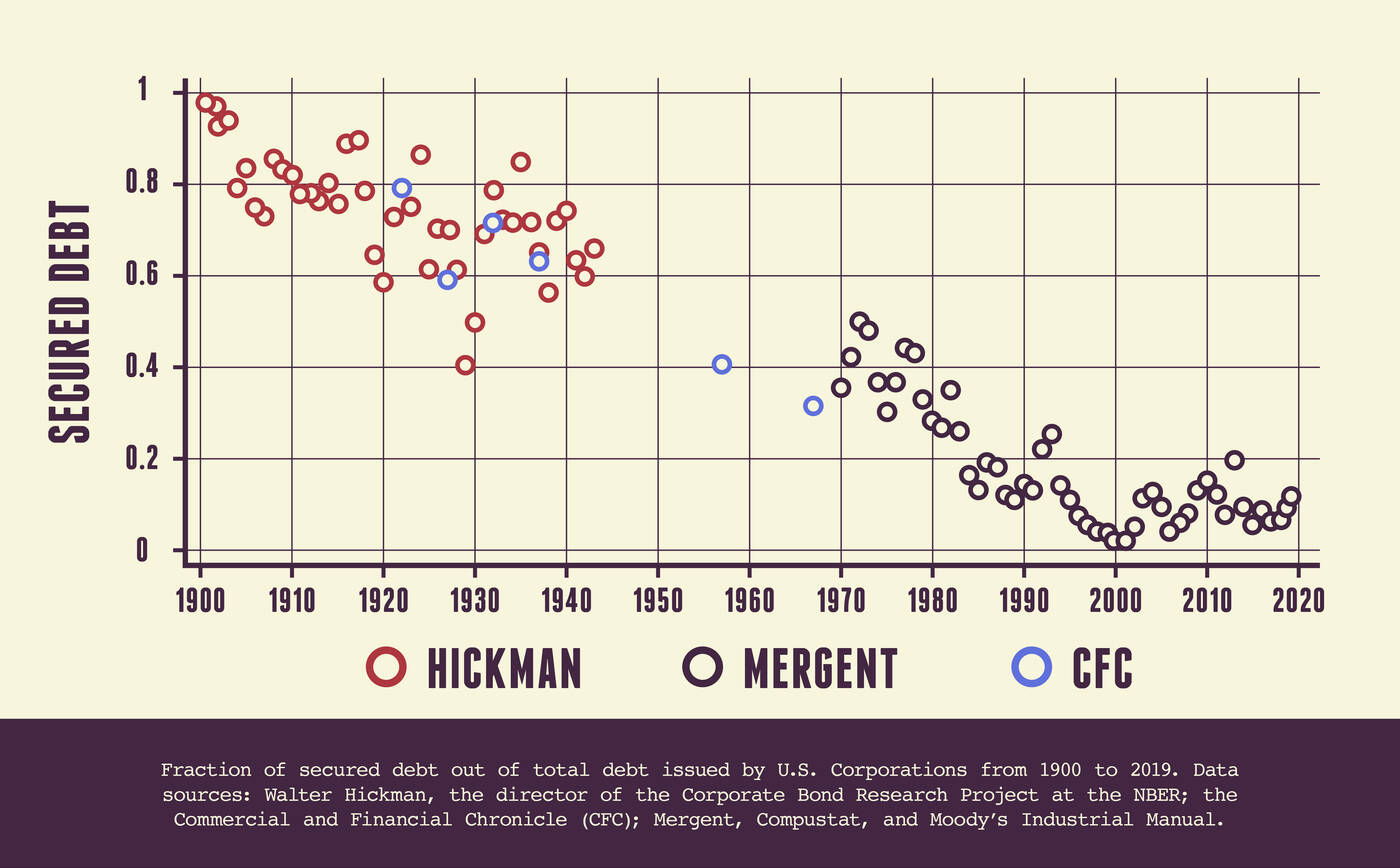

Indeed, the team analyzed the issuance of debt by U.S. corporations since 1900 and found that the percentage of secured debt (out of all debt) fell dramatically, from a peak of 98.5 percent in 1900 to just below 5 percent in the early 2000s.

This large swing was only able to happen because of financial developments throughout the twentieth century—such as improved accounting reports and disclosure requirements—that allowed lenders to better assess the reliability of corporations, Benmelech says. And once the door to unsecured debt was opened, corporations really dug in. Their strong preference for unsecured debt has had a lot to do with a growing recognition that, in a world riddled with crises, they need to retain financial flexibility.

“Because of the risk of financial crises,” he says, “firms now try to maintain an element of contingency: ‘I’m going to refrain from issuing secured debt in good times to keep my assets untapped so that I can go and tap them when I really need to.’”

Years ago, when Benmelech was a doctoral student, he became intrigued by the dynamics of secured debt. And while he was writing his dissertation, he discussed the topic with Rajan, who was one of his advisors at the time. “Both of us were fascinated by this phenomenon and wanted to pursue it,” Benmelech says.

So, they collected some initial data about the use of secured debt by U.S. corporations and identified a steady decline in its use in the early twentieth century. But as is often the case with life and work, other priorities took hold, and they postponed their research.

Benmelech, Rajan, and Kumar eventually resumed the investigation years later. The three researchers worked together to cull information on debt issuance by U.S. corporations from 1900 to 2021 from a variety of sources, including the National Bureau of Economic Research, financial publications, U.S. bond database reports, and manuals.

A clear trend emerged as they examined the data, Benmelech says: “We saw a rapid decline in the use of secured debt, especially by large publicly traded firms in the U.S. since the 1900s.”

The initial discovery and eventual confirmation and publication of this finding took place over the course of 21 years.

“What began as a discussion between a PhD advisor and a student,” Benmelech recalls, “turned out to be a long collaboration—probably the longest project I’ve ever worked on.”

Though the decline of secured debt has been steep overall, it hasn’t necessarily been a straight nosedive. Instead, the research shows that there were mini peaks and valleys that occurred amid the general decline.

Benmelech and colleagues found that the issuance of secured debt followed a countercyclical pattern to the U.S. economy—falling when GDP went up and rising when GDP went down—a trend that was particularly pronounced in the earlier part of the century and around times of financial crisis.

For example, the percentage of secured debt issued was as low as 40.5 percent just before the start of the Great Depression in 1929 and then, as economic conditions worsened, shot up to 85 percent in 1935.

In a similar manner, secured-debt issuance was 10.6 percent in the early throes of the global financial crisis in 2008 and continued to rise during the crisis until it hit 16.2 percent in 2010, after which it gradually lowered back down to 10.9 percent by 2019.

“It’s a trend that we actually saw in Covid as well,” Benmelech says. “Many firms had to raise money to weather the storm. But there was a real concern from lenders and bond holders, who thought, ‘The world is sort of coming to an end. How can we be reassured that firms will be able to pay us back?’ And so firms were more likely to issue secured debt because of the uncertainty.”

“Firms are becoming more and more reliant on intangibles rather than tangibles. But secured debt is a better friend of tangible assets.”

—

Efraim Benmelech

The research suggests that the high recurrence of economic downturns likely pushed U.S. corporations to prioritize unsecured debt in normal times so that they could reserve their assets to borrow money in hard times, when lenders tend to tighten the lid on their coffers.

“If I use secured debt when I’m doing well and the economy is doing well, what will I do if something bad happens, if we enter into a recession?” Benmelech says. “The main drawback of secured debt is this loss of financial flexibility.”

Why did the use of secured debt fall so drastically after 1900?

The researchers propose several potential explanations.

For one, the quality of the information available to lenders improved over time. Accounting practices at U.S. corporations made strides early in the twentieth century; then, in the 1930s, the Securities Exchange Commission was formed, leading to tighter regulations over firms’ business disclosures. Moreover, technological advancements over the years made any available information much easier to access.

With increased access to better information, “lenders or bond holders no longer had to rely only on the security of collateral,” Benmelech says. “They were able to say, ‘We can screen and monitor the firms better; we are not going to resort to the harsh measure of requiring collateral because we have enough reliable data.’”

The twentieth century also saw a shift toward stronger corporate governance—including more-transparent and -responsible rules, practices, and policies, often steered by a board of directors—as well as a shift in bankruptcy practices to prioritize lenders when a borrower goes into default.

Overall, these changes have made lenders increasingly confident that large corporations would repay their debt, even if it was unsecured.

What’s more, the nature of companies has changed. “The modern firm has fewer assets on its balance sheet,” Benmelech says, referring to the decline of traditional assets such as property and equipment that corporations could use as collateral. They have been relying more on intangible assets instead, such as brand name and intellectual property.

“Firms are becoming more and more reliant on intangibles rather than tangibles,” he says. “But secured debt is a better friend of tangible assets.”

Still, even though secured debt is no longer as popular among large companies as unsecured debt, it can have an important role to play—even when the economy is relatively strong.

In 2006, for instance, a time when the capital markets were thriving, Ford mortgaged nearly all of its domestic assets as collateral to raise a $23.6 billion credit line to overhaul its business.

“It was a move that was heavily criticized in the financial media and by experts who essentially said, ‘Ford is really betting on the house, because they’re using everything that they have to issue secured debt. And if something bad were to happen, they would have nothing left,’” Benmelech says.

Not even two years later, the Great Recession struck America. The crisis could have bankrupted Ford since it had no remaining assets to use as collateral for loans. Fortunately, the company had planned ahead and held onto enough of the cash it raised in 2006 to carry them through the recession.

The gambit ultimately turned out to be well worth the risk, allowing Ford to avoid a chapter 11 bankruptcy, unlike its local rivals in Chrysler and GM.

“There was a real concern that Ford was taking on too much secured debt, but they understood that they had to do it,” Benmelech says, “and that has proven to be very successful.”

Abraham Kim is the senior research editor at Kellogg Insight.

Benmelech, Efraim, Nitish Kumar, and Raghuram Rajan. 2024. “The Decline of Secured Debt.” The Journal of Finance. 79: 35–93.