The story’s lesson—that arriving at the whole truth often requires piecing together many separate bits of information—may seem obvious at first. Yet what if the investigators are motivated to observe only what they want to see?

That may be the case with how U.S. policymakers use scientific research, according to a new study in Science led by Dashun Wang, the Kellogg Chair of Technology and a professor of management and organizations at Kellogg, where he also directs the Center for Science of Science and Innovation (CSSI) and the Northwestern Innovation Institute, and codirects the Ryan Institute on Complexity.

U.S. congressional committees and think tanks draw from science, or the wide pool of existing research-backed knowledge, to stay as informed as possible when developing policies and legislation. Encouragingly, Wang and coauthors Alexander Furnas, a research assistant professor at CSSI, and Timothy M. LaPira of James Madison University, found a steady increase in policymakers’ use of science over the past 25 years.

“In some sense, the relationship between the two frontiers of science and politics is closer than ever,” Wang says. “Many of society’s challenges are linked to scientific development—the pandemic, climate change, AI—so it’s very welcoming to see that policymakers and the documents they generate are increasing in scientific reliance.”

However, as policymakers’ overall use of science has grown over time, so too has the divide between the kind of information that partisans on different sides of the political spectrum use.

Indeed, after examining tens of thousands of reports and policy documents published by the federal government and think tanks, the researchers found that only a small fraction (about five percent) of the science in these documents was cited by both Republicans and Democrats. This low overlap suggests that Republican and Democratic policymakers rely on mostly different pieces of information to guide their decisions—perhaps not unlike the way the blind men approached the elephant.

“Science is one of the tools that policymakers can use to learn about the state of the world, about what problems need to be addressed, and about the impact of interventions,” Furnas says. “So when partisans are using different sets of science and have different understandings of the state of the world, that can potentially cause problems for effective democratic governance and policymaking.”

Science on the rise

Congressional committees and think tanks are tasked with drafting documents that convey expert opinion on key topics to Congress, lobbyists, and various stakeholders. The process often entails citing scientific publications on all fields of knowledge, from language to particle physics, to inform their decisions and recommendations.

For their research, Wang, Furnas, and LaPira focused on a dataset consisting of congressional committee reports from 1995 to 2021 and committee hearings from 2001 to 2021 (49,345 documents); policy documents published by 121 U.S.-based think tanks after 1999 (191,118 documents); and the 424,199 scientific publications cited in these documents. Then they linked the scientific references identified in this first dataset to another massive database of scientific publications.

After examining this large pool of data, the researchers found that the number of scientific publications cited in policy documents increased steadily over the 25-year period, starting at 20 percent in 1995 and exceeding 35 percent by the end of 2020. The publications broadly covered 23 scientific fields and 17 issue areas.

“It’s generally good that the use of science in policy is increasing,” Furnas says, acknowledging that the reason behind this trend is not entirely clear.

One of the most likely reasons, he believes, is that access to science has expanded over time, which may have made it easier for policymakers to consume and cite more research. The increased use of science also “happened at the same time that there’s been a decline in substantive issue-area expertise and legislative capacity among staff in Congress,” Furnas says. “And so you might expect folks to use more outside sources and references.”

A lack of common ground

Though policymakers’ use of science appears to be on the rise, Wang, Furnas, and LaPira identified systematic differences between the kind of science that Republicans and Democrats tend to cite in their policy documents.

The researchers performed a statistical test that estimated there would be a natural overlap of 12 percent of the citations made by Republicans and Democrats. Yet a review of the documents found an overlap of only about five percent—less than half of the expected amount. Even after removing the publications that were only cited once (and therefore couldn’t be cited by both political parties), the actual overlap in citations was still about half the expected amount. This low degree of overlap was consistent throughout the study period.

“What we can infer is that when partisans are using scientific evidence in their policymaking process, they are not drawing broadly across all possibly relevant science,” Furnas says. “It’s at least suggestive of the fact that they’re drawing on the science that helps them make their point instead.”

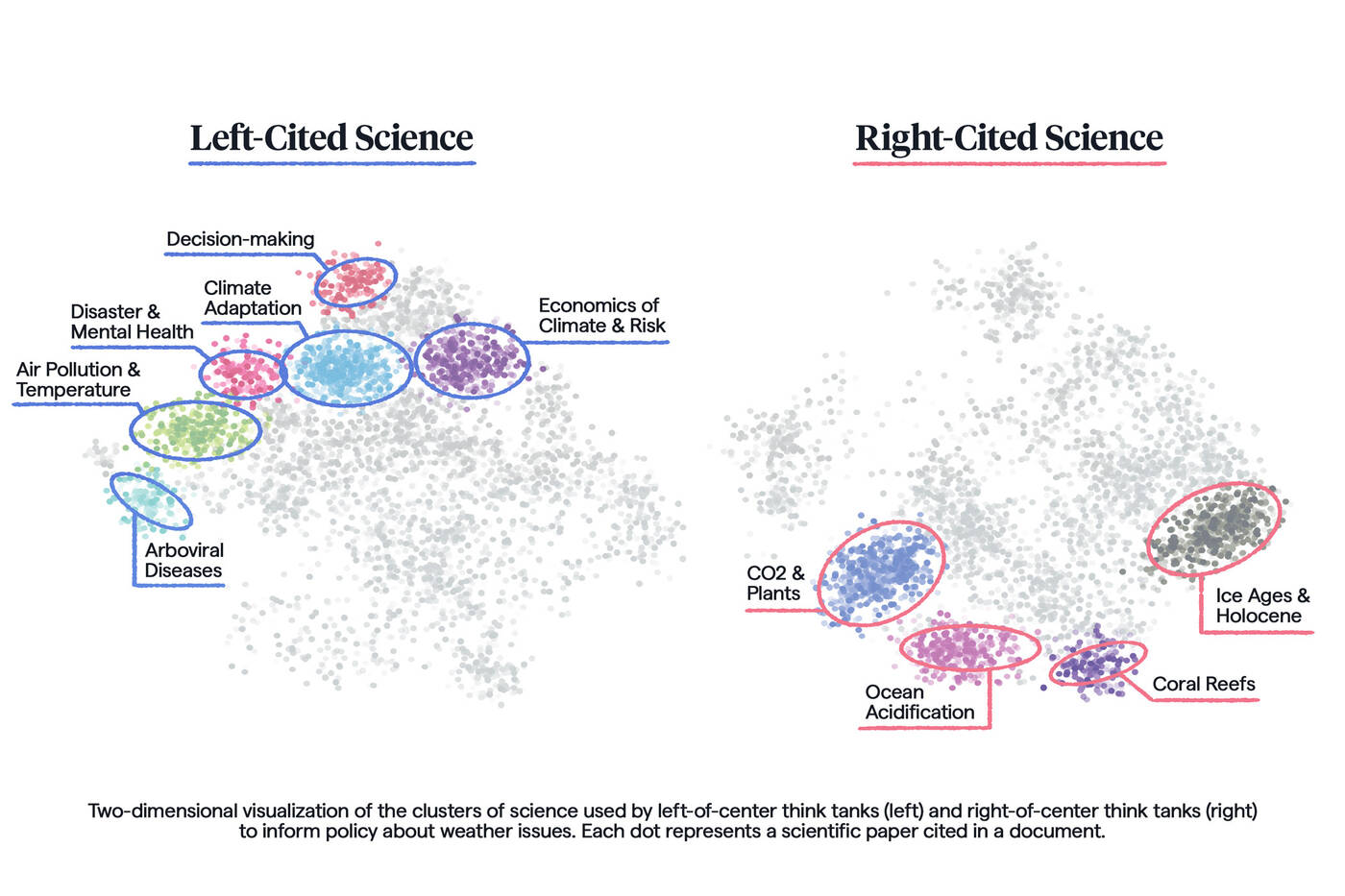

Indeed, policymakers on different sides of the political spectrum tended to cite different topics.

The researchers used a deep-learning algorithm to plot each of the cited scientific papers as a point in space, grouped by topic. This technique allowed them to quantify and visualize the distinct clusters of science that Republican versus Democratic committees and think tanks referenced in their policy documents.

Not only did Republicans and Democrats generally focus on different topics—a choice that might simply reflect their different agendas—but they also cited different scientific publications when drafting documents that covered the exact same topic.

In one such case, a left-of-center think tank (the Urban Institute) and a right-of-center think tank (the Employment Policies Institute) both drafted a document about the effects of raising the minimum wage, with nearly identical titles. Out of the 62 scientific papers cited by the two think tanks, only one appeared in both documents.

“Even when [Republicans and Democrats] seem to be focusing on the same topic—and writing about the same policy—they use different science from each other,” Furnas says.

In science we trust?

Although both Republican and Democratic committees cited more science in their policy documents over time, Democratic-controlled committees were nearly 1.8 times more likely to do so. In addition, committees that transitioned from Republican- to Democratic-party control made, on average, 196 more science citations after the transition.

The partisan difference was wider still for political think tanks. Left-leaning think tanks were five times more likely than right-leaning ones to cite science in their documents.

Democrats also tended to cite “higher-impact science, or papers that scientists themselves consider more important,” Furnas says. Specifically, democratic committees and left-leaning think tanks were more likely to cite science that was in the top five percent of the most-cited papers in a given field the year it was published and more likely to cite science that had passed peer review.

These trends motivated Wang, Furnas, and LaPira to investigate whether Republicans and Democrats have different levels of trust in science and scientists.

“Trust,” Wang says, “has always been an important factor in the use of information.” So the researchers conducted a survey of 3,500 U.S. political elites and stakeholders—including congressional staffers, bureaucrats, political journalists, C-suite executives, judges, and government officials—asking participants to rate how much they “trust or distrust scientists.”

The results indicated that Democratic political elites trusted scientists substantially more than their Republican counterparts.

For example, 96 percent of Democrats said they completely or partially trust scientists to create knowledge that is unbiased and accurate, compared with about 63.7 percent of Republicans. Democrats also rated the trustworthiness of two major scientific organizations in public policy much more highly than Republicans did: 61.2 percent of Democrats rated the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine as “very trustworthy,” compared with 22.8 percent of Republicans; and 40.7 percent of Democrats rated the American Association for the Advancement of Science as very trustworthy, compared with 8.2 percent of Republicans.

Exploring the overlap

On the one hand, the findings underscore stark differences between the information on which Republicans and Democrats rely to inform their policies, as well as the divide between their trust in science.

Yet the research also confirms there is a subset of information that policymakers on both sides of the political spectrum have used and trust. Having a better grasp of this overlap could prove critical to promoting more-effective policymaking and, in turn, supporting the growth of businesses and society overall.

“We want policymakers to have a good sense of what the impact of their policy is going to be so they can have some sort of certainty and stability,” Furnas says. “Nobody really wants unintended consequences.”

To that end, the researchers have been studying these areas of overlap as part of their ongoing exploration of the intersection between science and politics. “We want to drill down on this core overlap and understand it better,” Wang says. “Potentially, that could be a way to promote more trust in science and policy.”