Featured Faculty

Henry Bullock Professor of Finance & Real Estate; Director of the Crown Family Israel Center for Innovation; Co-Director of the Guthrie Center for Real Estate Research

Riley Mann

The consequences of war are devastating.

While it’s often the most-visually striking results that grab our attention, in examining the costs of war, it is crucial to understand how it affects the economy.

“Of course, economic consequences do not encompass all of the misery that war inflicts on people,” says Efraim Benmelech, a Kellogg professor of finance and economist who studies the economics of conflict and national security. “But eventually, the loss of human capital—of people—and the destruction of property affect a country’s economic well-being, and to an extent, it does subsume some of that misery.”

While there are past studies that have looked at the impact of war on the economy, most have centered on a narrow number of wars, regions, or years. Benmelech sought to widen the scope of this prior work and collaborated with Joao Monteiro of the Einaudi Institute for Economics and Finance to investigate the macroeconomic consequences of wars across the globe over a period of roughly 75 years.

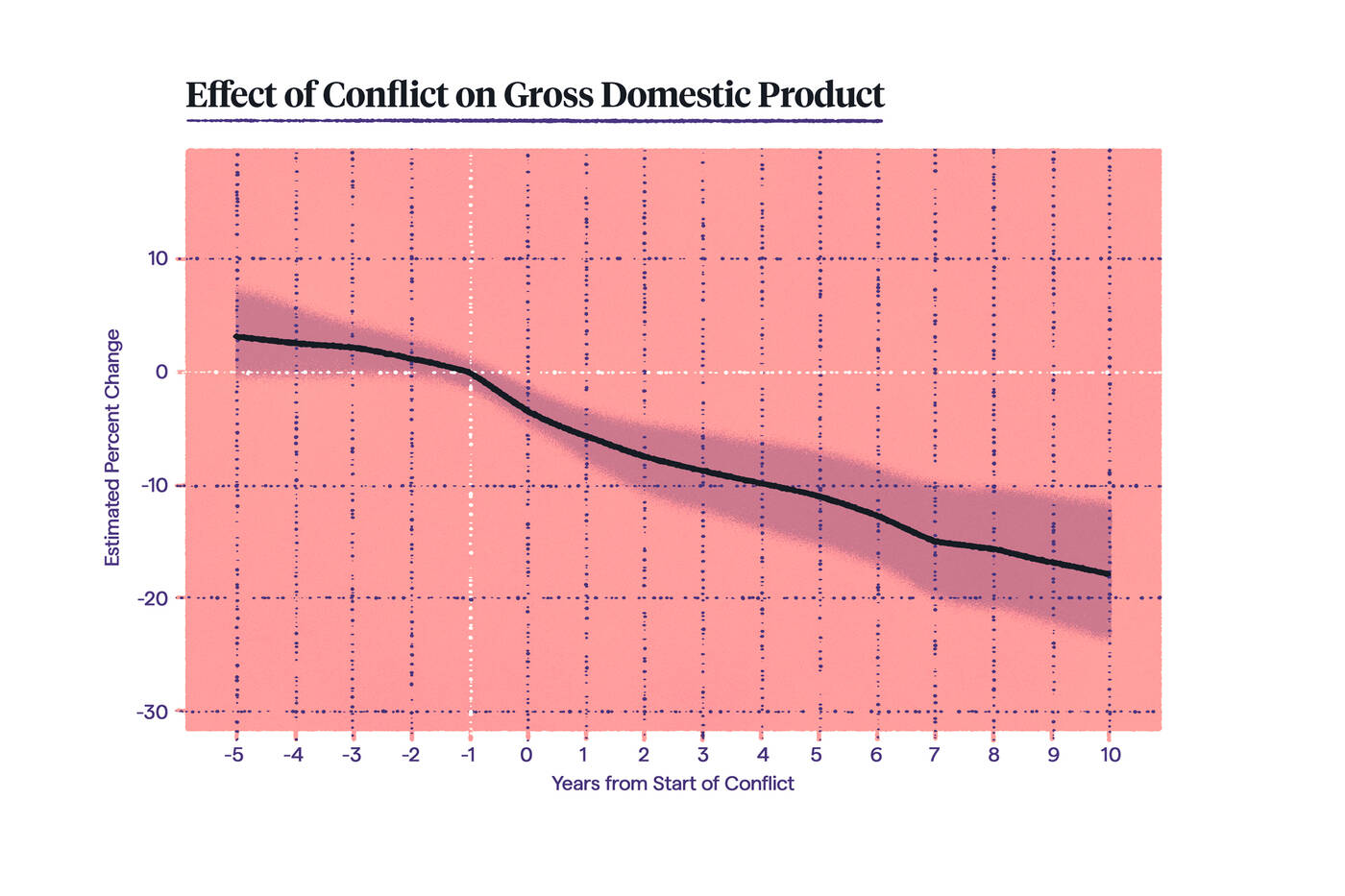

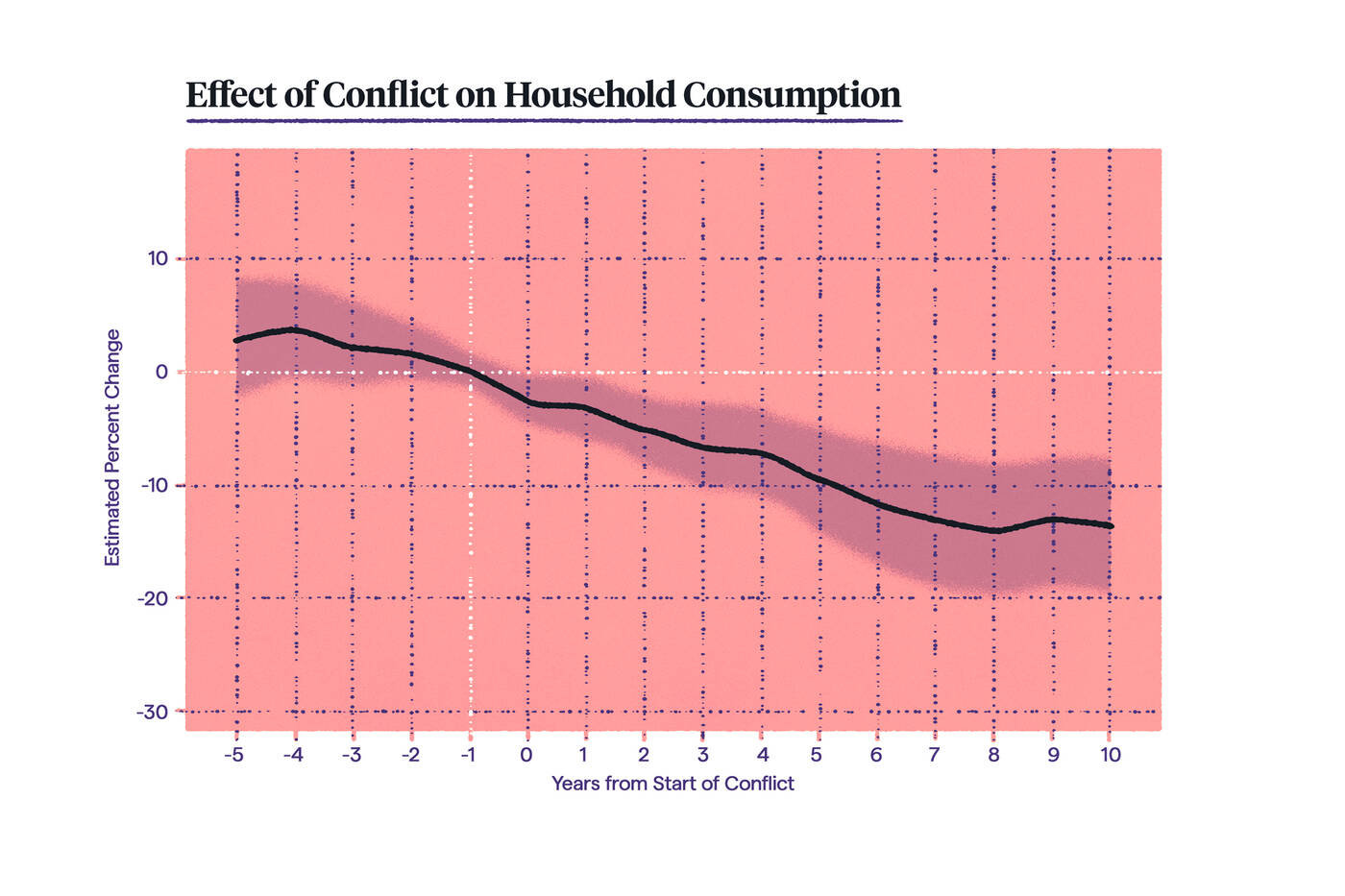

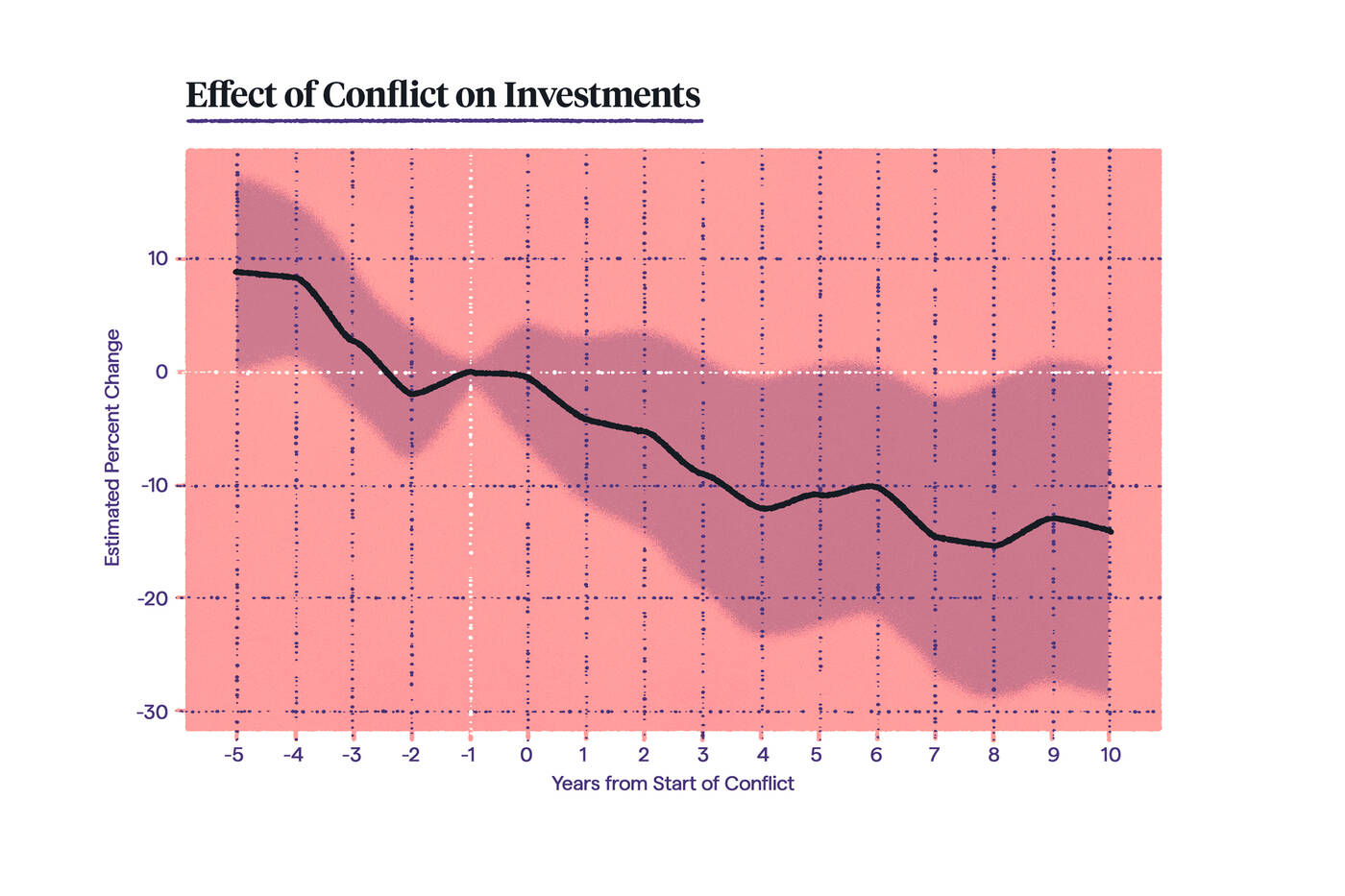

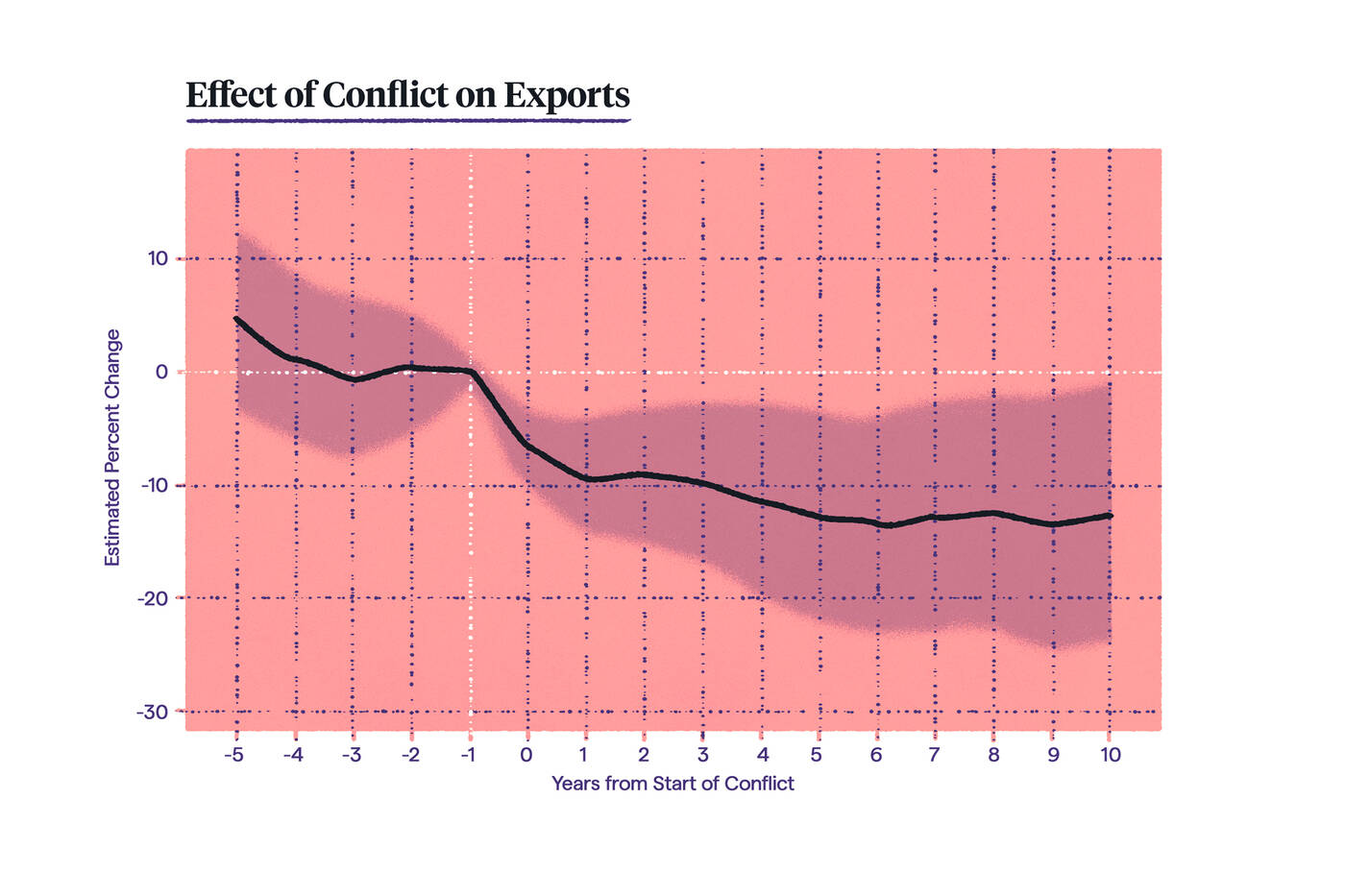

Benmelech and Monteiro analyzed more than 100 wars in the post–World War II era and found that they led to severe and persistent negative effects on the economy of all the countries entangled in conflict. The consequences included a significant and long-lasting drop in real GDP, collapsing investment, the deterioration of government finances, and a sharp rise in inflation.

Collectively, the findings make clear that the economic toll of war extends beyond the immediate costs of battle, leaving deep and lasting scars on the broader economy.

“There are some wars you cannot avoid,” Benmelech says. “So it’s important to know what the consequences are. And the quantification of the effect of wars is that wars are bad economic shocks.”

For their study, the economists drew from various publicly available records—including the Uppsala Conflict Data Program and the Peace Research Institute Oslo Armed Conflict Dataset—to identify all wars worldwide that took place from 1946 to 2023.

To qualify as a war, it had to be an armed conflict over a difference about government or territory, involve at least one state government (or country), and lead to at least 25 battle-related deaths per year.

The researchers examined 135 such conflicts across 115 countries.

For each war, they set the start of conflict as day zero and then observed what happened to a battery of economic indicators for each country involved from five years before to 10 years after the war’s onset.

They also matched each of the countries in war to a selection of 221 countries that were similar in terms of GDP, region, debt, and level of democracy but not involved in a war during the same period. By benchmarking the economic performance of warring countries to these control countries, they were able to rule out factors other than war, such as natural disasters or poor governance, that could have otherwise significantly changed a country’s economy.

“That enabled us to show that there were no pre-trends, meaning that we could actually attribute the decline in economic conditions to the wars themselves,” Benmelech says.

A common pattern emerged among the countries at war.

First, war triggered an immediate increase in military spending along with a decrease in spending elsewhere. Military expenditures on average rose by about 9 percent at the onset of war and stayed elevated for three years, which was the median duration of a war.

Next, war led to the destruction of part of a country’s territory and physical assets such as buildings and infrastructure.

And finally, war reduced overall productivity, not only because it disrupted production but also because it made it more likely for resources to be misallocated, people to be displaced or killed, and institutional control to be eroded.

War in effect shrank both the availability of a country’s assets as well as the efficiency with which they were used, ultimately reducing its economic output for an extended period of time.

As a result, practically all of the economic measures that the researchers looked at worsened on average, even after adjusting for inflation.

Real GDP fell by about 13 percent, with no evidence of recovery even a decade after the onset of war. Household consumption declined by about 11 percent. Investment in the countries’ structures, technology, and other areas collapsed, dropping by nearly 14 percent. And there was a significant decline in exports (roughly 13 percent) and imports (roughly 7 percent).

War also had a negative effect on the government’s budget. Average revenue decreased by around 14 percent and tax revenue by about 9 percent. Even though wartime expenses remained about the same as before (with military expenses up and other expenses down), the large drop in revenue still meant that the country’s risk of running a deficit increased by roughly 9 percent.

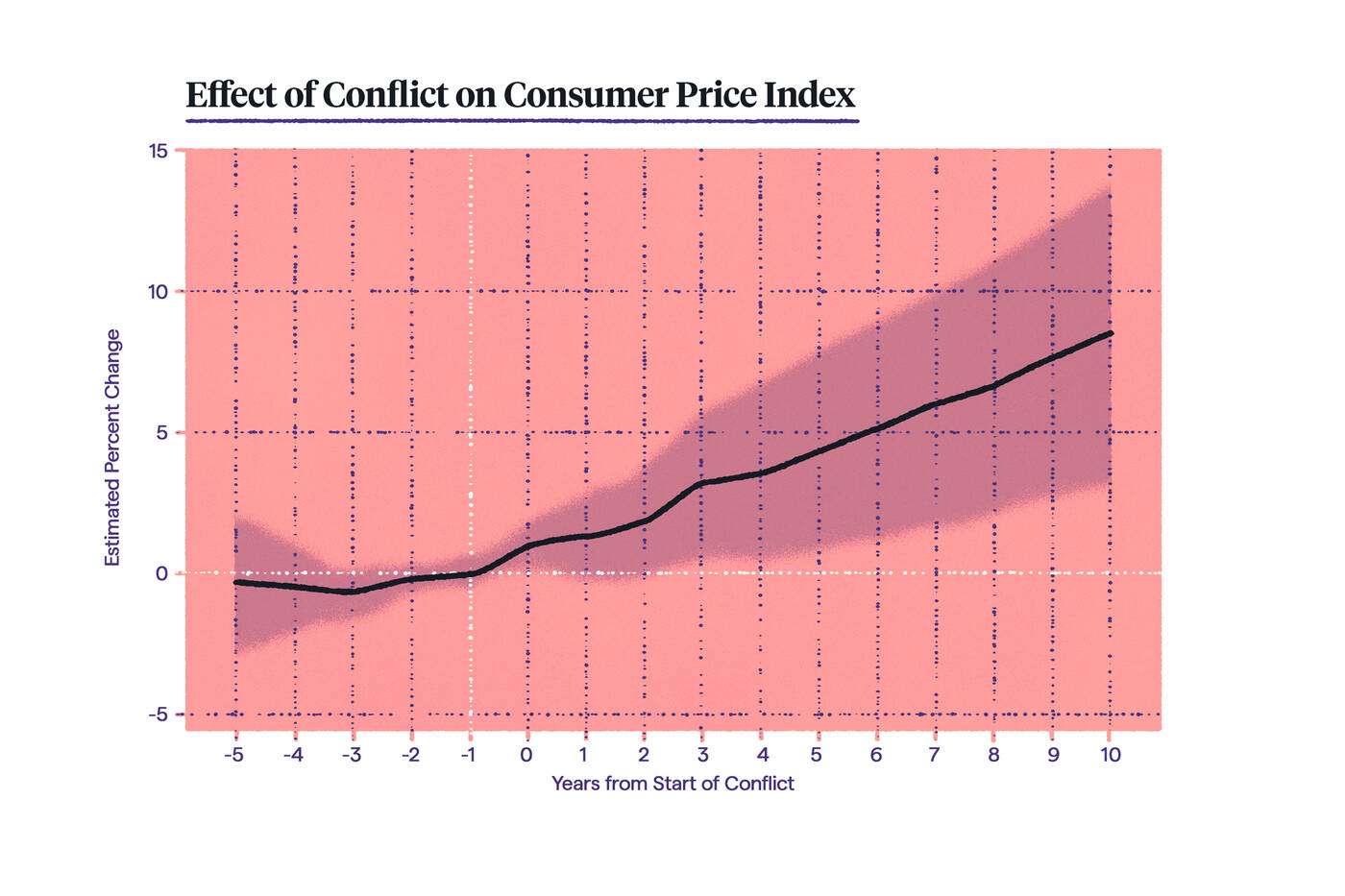

In response to all of these fiscal pressures, most countries resorted to issuing more currency, which propelled inflation.

“Wars have been financed mostly through money printing and inflation,” Benmelech says. “The reason that we see a decline in real GDP is mostly because of that inflation. And as we all know, inflation has some very adverse consequences for households.”

Indeed, price levels rose by nearly 50 percent and remained elevated for years after the start of a war. Inflation, in turn, eroded real debt and depreciated the nominal value of local currency significantly—an effect that persisted 10 years after the start of war. This not only raised costs and interest rates for people in the country but also further depressed investment.

But not all wars produced the same effects, the researchers discovered.

For example, there was a striking difference between the way that intrastate wars (within a country) versus interstate wars (between countries) affected the economy. Real output—the total quantity of goods and services a country produced—fell by 20 percent in intrastate wars but only 10 percent in interstate wars. This underscores just how much more damaging civil wars can be for a country’s economy compared with wars between nations.

“In past centuries, war used to be mostly between state entities. But the more common kind of war that we’ve seen in the second half of the 20th century and the first quarter of the 21st century are intrastate wars between government and nongovernment actors,” Benmelech says. “To that extent, it’s incredibly important to study these differences, which have been largely neglected in the literature.”

The researchers also found differences for countries that won versus lost a war. About 10 years after the onset of war, winners saw a slight (non-statistically significant) drop in real output relative to countries that didn’t go to war, whereas losers saw a 24 percent decline in real output—an estimated loss of $11.7 billion. This suggests that the losing countries disproportionately bore the economic costs of war, even if both winners and losers saw a sizable drop in real GDP.

As a whole, the analysis confirmed what many scholars and governments have long reported: “The overall effect of war on the economy is negative,” Benmelech says. Even 10 years after the onset of war, “everyone seems to be losing.”

Even though the findings illuminate the clear economic downsides to war, they should not necessarily be taken to mean that a country should never engage in one, according to the researchers. Instead, the research offers a way for politicians, leaders, and scholars to quantify the effect of war on the economy if and when the time comes.

Europe, for example, has been in the tough position of having to decide how much to invest in their militaries because of the looming threat of war after Russia invaded Ukraine.

“I’m not saying that Europe should avoid conflict altogether or, on the other hand, that Europe should necessarily appease Russia at any cost [to avoid war],” Benmelech says. “But what the research does provide are the numbers, so that, when decision-makers look into them, they can do their own cost–benefit analysis and at least realize what the cost would be.”

*

Infographic illustrations by Michael Meier.

Abraham Kim is the senior research editor of Kellogg Insight.

Benmelech, Efraim, and Joao Monteiro. 2025. “The Economic Consequences of War.” Working paper.