Featured Faculty

Member of the Department of Accounting Information & Management faculty from 2008 to 2014

Artwork by Yevgenia Nayberg

Skyrocketing compensation for CEOs of U.S. companies, which has risen disproportionately to compensation for other workers over the past several decades, has provoked no end of public outrage. It has been called unfair, unseemly, unwise, unjustified. But is that the whole story? Anup Srivastava, an assistant professor of accounting information and management at the Kellogg School of Management, wondered whether today’s CEOs might actually possess some subtle quality to justify the extra pay. “Is there some ability that has made them more important over the years?” Srivastava asked.

His own research had shown the negative effects of hefty CEO pay packages. First, Srivastava found that when CEOs have a large stake in their company—a median level of $100 million—they start “doing funny things,” like using creative accounting to try to portray the firm in the most positive light, which in turn can keep stock prices high. Later, he showed that highly paid CEOs will sometimes do the opposite, deliberately missing earnings targets to sink stock prices in advance of being granted new stock options. “My past research has shown that abnormally high compensation provides incentives to managers to play with accounting tricks,” Srivastava says. (For Clare Wang’s insights into compensation at the other end of the spectrum—$1 CEO salaries—read here.)

But despite this evidence of bad behavior, he wondered whether there could nonetheless be a sound explanation for rising CEO pay. In a recent paper, Srivastava found that the extra pay can be at least partly explained by the increasing importance of executives’ ability to predict future risks to the firm. By tying part of their compensation to this risk-forecasting ability, firms can attract CEOs who are better at it. As companies have become on average smaller and “more susceptible to failure due to sudden changes in the business environment,” writes Srivastava, this ability has become increasingly important to ensure a company’s survival and growth.

Today, companies operate in a less certain economic environment. Over the past two to three decades, says Srivastava, “firm failure rates have increased; the period at which a firm is a market leader has declined; the composition of Fortune 500 companies changes more frequently; and profits have become more uncertain.” Could it be possible that boards are responding to all those factors by selecting the right leader—and by writing the compensation contract such that it is in their leader’s best interest to put effort into forecasting future scenarios? This could enable the firm to plan better for future contingencies and to take advantage of emerging opportunities.

“It appears CEOs can forecast risk that the market cannot. That’s their extraordinary ability.”

To answer his questions, Srivastava looked at how CEOs manage their personal portfolios, measuring their forecasting ability by the extent to which their own trades “contain information about future firm risks unknown to the market,” as he writes in the paper.

“The theory suggests that CEOs are averse to the risks of their own firm,” he says. “They do not want it to fail because they do not have diversified eggs in their nest.” Because stock options have become a far bigger source of compensation for CEOs than salaries or cash bonuses—CEOs on average hold stock options worth ten times their base salaries—they have disproportionate economic exposure to their own firms.

“Let’s say I’m the CEO, I hold stock in the firm, and I also have stock options in the firm,” says Srivastava. “If I expect my firm to fail in the future, say one to two years from now, then I’ll sell my stock or exercise my options and I’ll take that money out and put it in diversified funds. I might lose the time-value of stock options, but I can at least protect their in-the-money values. So my personal actions to exercise the stock options early may be related to my ability to forecast the future risks of my own firm.”

In fact, Srivastava did find a strong linkage between future risks to the firm (but unknown to the market) and CEOs exercising their stock options early. “It appears CEOs can forecast risk that the market cannot. That’s their extraordinary ability.”

He then evaluated whether boards “provide high-powered incentives” that help lure the best risk forecasters. Stock options, he found, are indeed just such incentives. “We are all self-interested individuals,” says Srivastava. “If I care about my wealth, I want to protect my wealth portfolio from future risk.” Because options’ value fluctuates much more than the stock market, just a 10 percent change in the market can cause a 50 percent change in options. Boards want CEOs to forecast future risk so that they can use that knowledge to benefit the company. So they incentivize CEOs to spend more time and energy on forecasting risk by linking it to their own compensation.

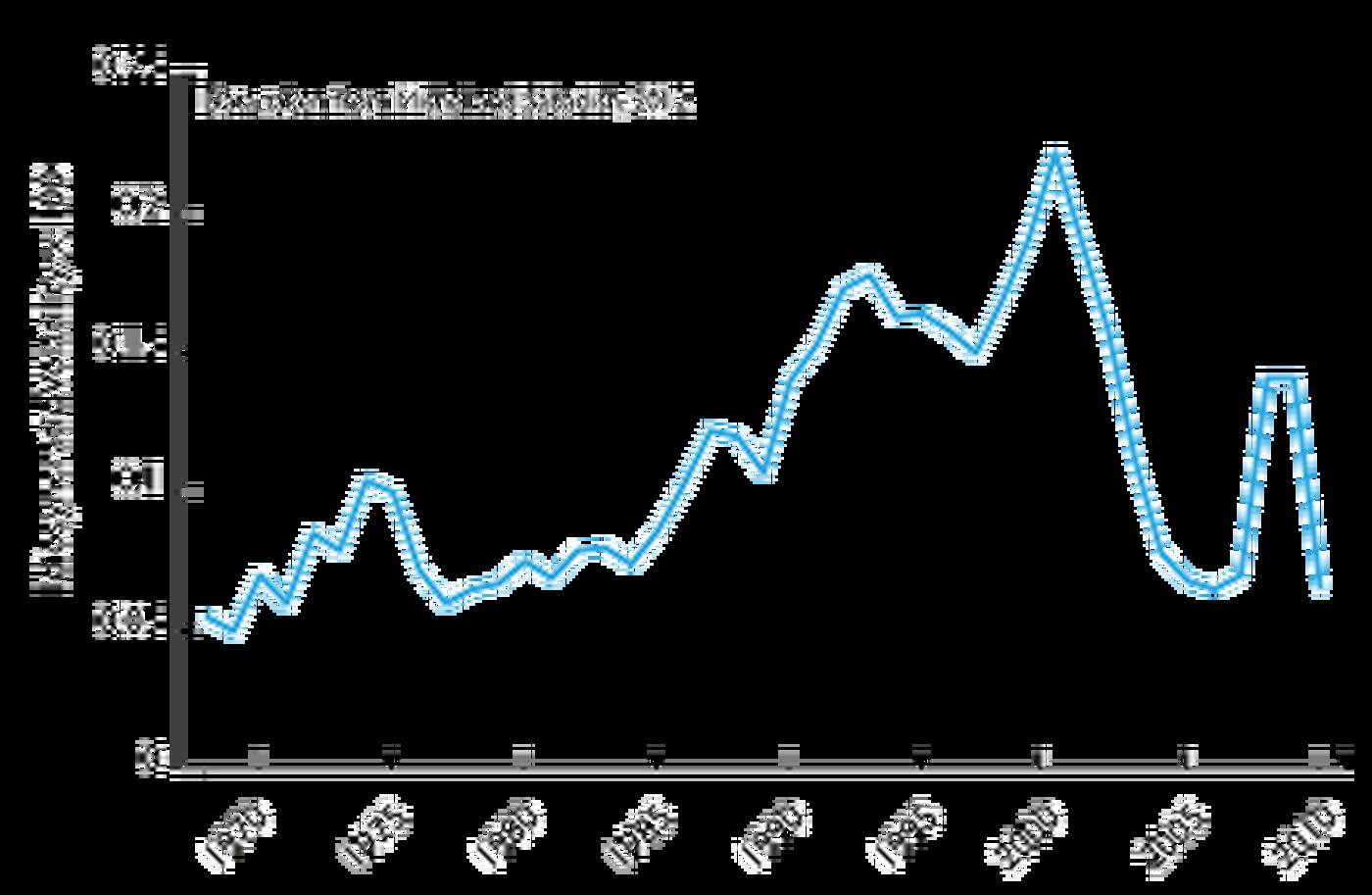

Srivastava found that these “high-powered” components of CEO pay packages are linked to the risk-forecasting ability—whereas salaries and bonuses are not. In fact, when he compared 40 years of stock-option compensation to 40 years of “idiosyncratic volatility,” a measure of firm risk, he found that the graphs matched up (see below). “Firm risk peaked when stock-option compensation peaked,” he says. “It’s more than a coincidence.”

Ultimately, the findings offer an economic explanation for the huge rise in CEO compensation over the past several decades. As he writes, “CEOs possess an ability that has become increasingly crucial for organizational success.”

Still, Srivastava cautions that his thesis “in no way overturns the widespread labels of ‘outrageous’ and ‘unfair’ attached to CEO compensation in the popular press and academic literature.” Opportunism may well still play a role in the decades-long spike. Instead, Srivastava’s work suggests that more reflection is needed. “I’m saying, ‘Wait a minute. Before we totally dismiss the increase as opportunistic and outrageous, it’s possible that there is some kind of economic explanation.’”

Srivastava, Anup. 2013. Do CEOs possess any extraordinary ability? Can those abilities justify large CEO pay? Asia-Pacific Journal of Accounting & Economics, 20(4), 349-384.