Strategy Nov 3, 2022

Transparency Requirements May Not Curb Sneaky Behavior

A new study finds that it is possible to maintain plausible deniability, even if your conversations are later made public.

Michael Meier

Transparency requirements are often put in place to ensure that decision-makers follow the rules. After all, sunlight is the best disinfectant, right? This is one reason many boards keep a record of meeting minutes, managers exhaustively document their hiring processes, and traders are required to communicate on monitored platforms.

But a new study suggests that these kinds of measures may not always be very effective. Nemanja Antic, an assistant professor of managerial economics and decision sciences at Kellogg, and his colleagues find that it is often possible for people to share enough information during deliberations to get the outcome they want, while still retaining plausible deniability about how much they know should their communications ever be made public.

In other words, transparency can often be gamed.

In many situations, “you’re able to have the same outcome that you would’ve had without transparency, and that was very surprising for us,” says Antic.

Depending on your perspective, this ability to bypass transparency is really good or really bad.

Take individuals under surveillance, who of course may not be doing anything unethical or illegal at all. For them, the study offers a roadmap of sorts for how to gather information and use it to make the best possible decision, all while retaining enough uncertainty about what you know to keep you safe from possible punishment. This could be useful for activists who wish to share information under the watch of an authoritarian government or for business leaders who wish to discuss a possible acquisition without their words later being taken out of context by antitrust regulators (or really for anyone passing along sensitive information via an electronic platform that could one day be hacked).

But the finding also has implications for governments, regulators, and others who design and use transparency measures. To ensure their own interests aren’t trampled, they may need to rely on other strategies, like restricting how and when information is shared.

Covert Communication

For insights into how scrutiny might affect decision-making, Antic and his colleagues, Archishman Chakraborty of Yeshiva University and Rick Harbaugh of Indiana University, turned to game theory. They built a mathematical model in which two parties with a shared interest trade information back and forth before making a final decision—all under the eye of a watchful observer with slightly different interests.

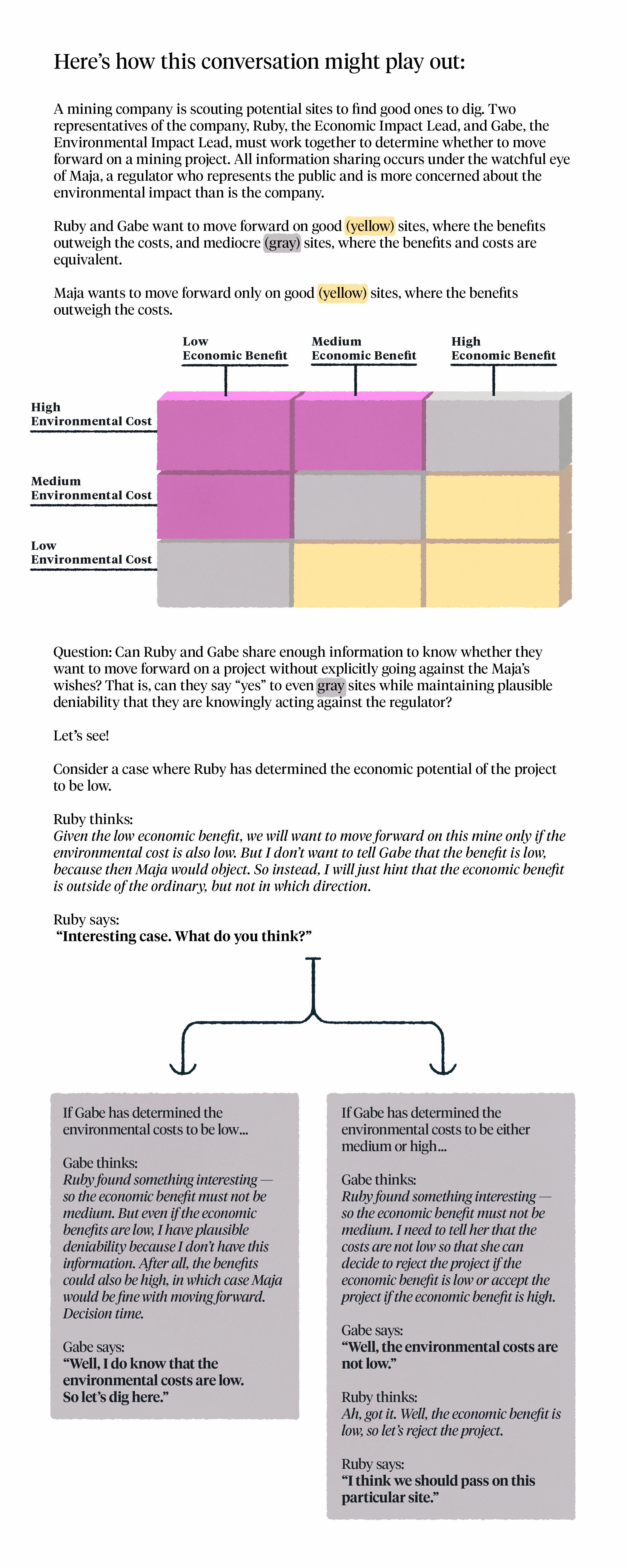

To understand how their model works, and thus how transparency can be gamed, consider a scenario in which two managers are working together to evaluate potential sites for a new mining operation. The first manager has information about the economic impact of the new sites—small, medium, or large—while the second is armed with information about its small, medium, or large environmental costs. In order to know whether to proceed with a given site, they must both contribute information to the decision.

Meanwhile, the general public also has an interest in whether a particular site is selected, and it weighs the environmental impact more heavily than does the firm.

Sometimes, the firm and the public are on the same page. For “good” sites, where the economic benefit exceeds the environmental costs, both the firm and the public agree that the project should move forward. And for “bad” sites, where the environmental cost exceeds the economic benefit, everyone agrees the project should not move forward. But when the economic benefit and environmental cost are roughly similar—for instance, a project with a medium economic benefit and a medium environmental cost, or a high economic benefit and a high environmental cost—the parties are at odds. The firm wishes to move forward with these “mediocre” sites, while the public would not approve.

Critically, the public can find out what information managers share with one another to make their decision. This means that managers cannot knowingly act on information in a way that goes against the public interest, or they will face punishment. As a manager, says Antic, you must show that “given all of the available information you had at the time, you made a decision that was palatable to the public.”

If the public can’t be sure whether the managers actually knew that they were acting against the public’s wishes, however, managers will be given the benefit of the doubt. This means that managers who move forward on a mediocre site can avoid punishment if they can also show that, given the information that was discussed, the site could also have been a good one.

The researchers find that, for a scenario like the one described, it is always possible for managers to make the same decision they would have wanted to make anyway, while still retaining plausible deniability. By carefully planning the order in which information is shared, and stopping before everyone’s cards are on the table, managers can work together to suss out whether to move forward, while not publicly distinguishing between the good sites that the public would approve of and the mediocre ones it would not.

(article continues below)

For instance, a manager might say, “What do you think” as a way of hinting that they have information about the site that they can only share after the other manager has provided additional context. Or a manager might say that the costs are “not high,” leaving it unsaid whether the costs are small or medium.

“These conversations are about providing information, but importantly also about providing context for how any future comments will be interpreted,” says Antic. “You want to have enough information to make a decision, but not too much information.”

He points out that there are even instances in which parties might welcome public scrutiny. “Let’s say there’s quite a lot of distrust” between a firm and the general public, Antic says. In situations where the public is likely to object to a firm’s decision, the firm might actually invite transparency, because by revealing to the public exactly what they knew when the decision was made, the firm can show that the conflict of interest is not as great as the public imagines.

Preparing for Scrutiny

The usefulness of plausible deniability is nothing new. Organizations that know they will be scrutinized may deliberately provide their leaders with as little information as possible. Recall how, with respect to the CIA’s “enhanced interrogation techniques,” the White House Counsel told President George W. Bush, “Mr. President, I think for your own protection you don’t need to know the details of what is going on here.” Or similarly, a leader might deliberately avoid seeking information from a subordinate so as not to be held accountable for what they learn. These strategies, of course, can lead to terrible decisions.

“But the surprising lesson from this paper is that it is often possible” to get the outcome you want while maintaining this plausible deniability, says Antic.

For people sharing sensitive information under threat of surveillance, the study suggests that there is little to be lost—and a lot to be gained—by communicating in manner that an outside observer cannot object to, even if those communications become somewhat more roundabout. In the researcher’s model, this meant trading pieces of information back and forth with the understanding that your conversation partner’s future remarks will be understood in the context provided by your statements. Lawyers that represent firms in antitrust cases, for instance, often caution against using shorthand like “Get rid of them” that could later be misinterpreted. They suggest bookending any sensitive details being discussed with the exact context in which they should be understood. In other words, it’s generally wise to stick to language that would be acceptable if it were made public, even if you don’t think it will be made public.

For those in charge of implementing transparency requirements, the lessons are equally stark. Other measures, like restricting how the parties can communicate with one another, may be necessary to prevent transparency from being gamed.

In fact, Antic suggests, this may be one reason why sunshine laws and other transparency requirements don’t always have much impact. He points to some of the policies intended to eliminate bias from hiring processes, like blind hiring, or auditing a hiring committee’s communications. If a committee is nonetheless able to design the hiring process, and in particular control the information that is shared, they may be able to maintain plausible deniability without changing the final hiring decisions, and so the policies may not be particularly effective.

“It perhaps shows why some of these policies don’t result in actual change,” says Antic.

Jessica Love is editor-in-chief of Kellogg Insight.

Subversive Conversations. Antic, Nemanja, Archishman Chakraborty, & Rick Harbaugh. Working paper.