Organizations Social Impact Nov 4, 2025

What Does It Mean to Be Rational?

It’s more than just being logical and analytical, research shows. But misperceptions can affect how people are treated and how much they are paid.

Yevgenia Nayberg

When you think of a rational person, what comes to mind? Do you picture a person who is logical or one who is trustworthy? Is the person a woman or a man? A scientist, an investor, or an artist?

“If I were to ask people for the definition of ‘rational,’ most might say it’s someone cold and calculating—we’re rational when we are competent and think in a very logical, straightforward, analytical way,” says Tessa Charlesworth, an assistant professor of management and organizations at Kellogg.

But when Charlesworth and colleague Charles Dorison of Georgetown University studied how people actually defined rationality—based on word embeddings of a massive collection of internet text—they realized that this stereotypical view of rationality only tells half of the story.

On the one hand, their study of real-world text confirmed that most people did associate “rational” with words like logical, analytical, and efficient. On the other hand, however, most people also associated “rational” with words like reasonable, ethical, responsible, and trustworthy—attributing much more warmth to the term than previously expected.

When people write about the most rational person they can think of, “they might say, ‘My friend is really rational not only because she’s logical but also because she’s really dependable,’” Charlesworth says. “There are two subcomponents of rationality—an analytical side and an interpersonal side—and people often used them equally and interchangeably.”

After figuring out how everyday people really think about rationality, the authors explored stereotypes linked to the word. Across 66 social groups, they consistently found strong associations between “rational” and groups of people that had more power and status. For example, “rational” was associated with men more than women, with young people more than old people, and with the rich more than the poor.

Rationality is a prized trait—one that is often seen as the very essence of humanity, according to Charlesworth. So these seemingly innocent associations can have serious implications on the way that people are seen and treated in society, including what kind of careers and salaries people get.

“A lot of other stereotypes are underwritten by the fundamental judgment of how intelligent or rational we think people are,” she says. “For example, stereotypes about which careers are ‘good’ or ‘bad,’ or which occupations deserve to be highly paid or not—these kinds of stereotypes seem to arise from the foundational idea of who, and what jobs, are rational.”

840 billion words

The data that Charlesworth and Dorison examined for their study consisted of 840 billion words—widely considered a representative sample of online text in 2014. The words were pulled from everything archived on the internet in English, from blog posts to Google Books entries.

Then they used an algorithm to compress this large data set of language into word representations—maps that measure how closely a word is related to other words.

“The algorithm essentially goes through all the pairs and co-occurrences of words. Then it uses those co-occurrences to make a map where words that are close on the map have also appeared a lot together and have higher similarities in meaning,” Charlesworth says. “‘Bread’ and ‘butter’ are really close, for instance, but ‘bread’ and some other random work like ‘forest’ or ‘bike’ would be much further apart.”

The algorithm repeated this process over and over again until it landed on the best representation or map of all the words’ meanings.

For “rational,” the words and traits that had strongest association could be categorized into two general categories. The first included words that indicated logic, concision, and practicality (which the researchers referred to as “analytical rationality”). The second consisted of words characterized by reliability, trust, and understanding (or “interpersonal rationality”).

The combination of these two descriptions of rational—the analytical and interpersonal components—made up most of the word’s meaning.

Stereotypical associations

In addition to defining “rational,” Charlesworth and Dorison’s analysis revealed associations between the word and more powerful groups of people, reflecting a new dimension of stereotyping that past research has largely overlooked. They found that “rationality” was associated much more closely with historically dominant groups across the 66 social demographics that the team examined—including differences by gender, age, race, sexual orientation, and social class.

“There is a tremendous utility in stepping out of our ivory tower and thinking about how these concepts are actually used and grounded in how people actually talk.”

—

Tessa Charlesworth

For example, there was a significantly stronger association between “rational” and “rich” than there was between “rational” and “poor.” The result was the same in the case of “rational” and “white” (versus “Black”), “men” (versus “women”), “manager” (versus “laborer”), and “citizen” (versus “immigrant”), among many others. This link between rational and the dominant group was equally as strong when people used either the analytical or the interpersonal meaning of the word.

“What this means is that, in everyday language, all of those high-power groups—rich, straight, white, etc.—occurred much more frequently with rationality, whereas their lower-power counterparts occurred much less frequently with rationality,” Charlesworth says.

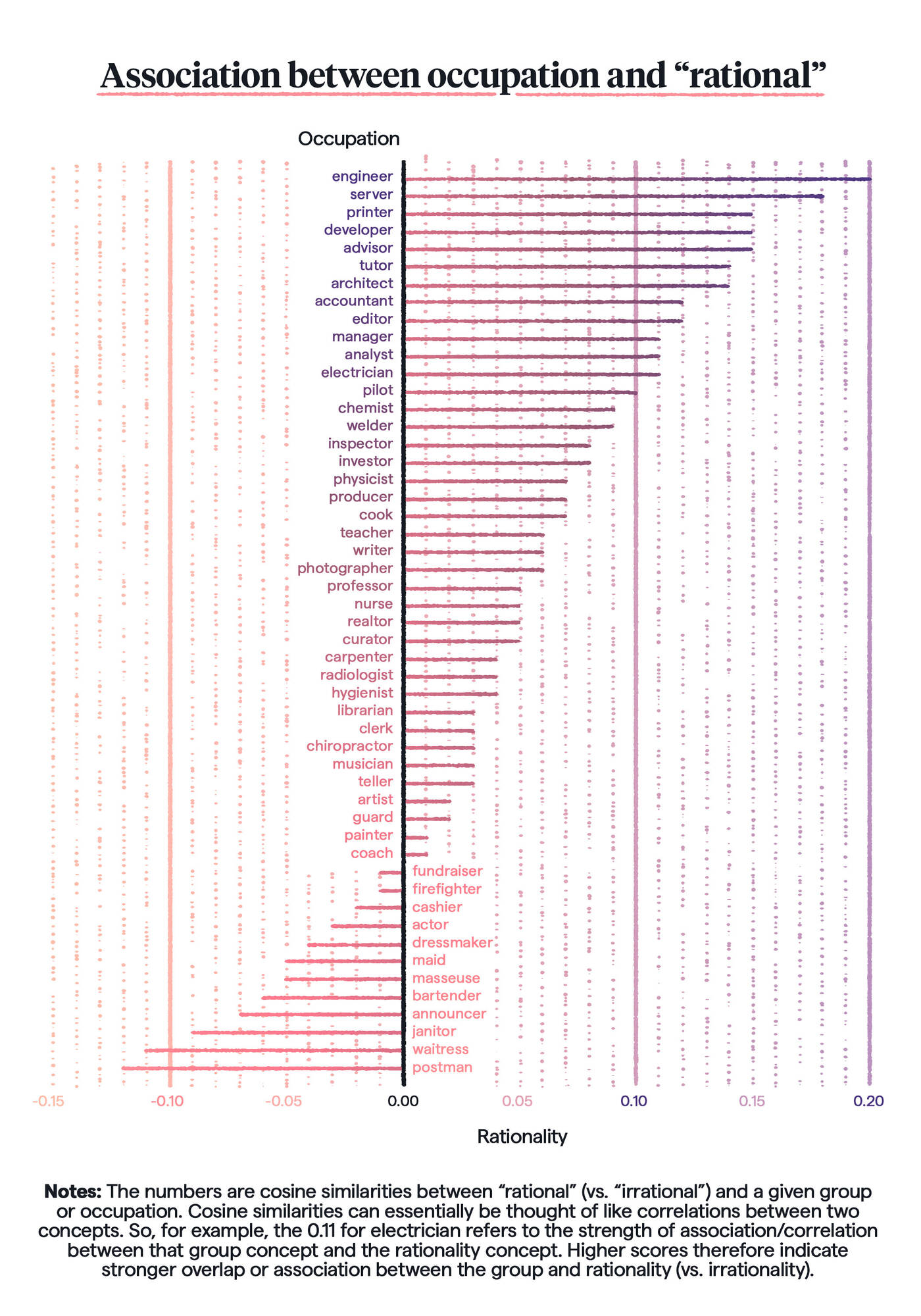

The researchers also found that people associated “rational” more closely with certain jobs, including those that are often high status, such as engineer, technician, programmer, developer, and advisor. More rational-stereotyped occupations were also those that had fewer women, more white people, and fewer Black people.

What’s more, occupations stereotyped as “rational” were those that gave the highest pay but only for men, based on wages reported by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. That is, the more a job was stereotyped as “rational,” the larger was the pay gap between men and women.

When they dug deeper, the researchers found that most of this difference between rationality stereotypes and pay gaps was driven by analytical rationality. So, jobs stereotyped with the cold and calculating type of rationality had a large gender pay gap. In contrast, jobs stereotyped with the interpersonal type of rationality, which emphasizes ethics, trustworthiness, or dependability, had little difference in pay.

Some of the jobs with the strongest stereotypes and the widest gender pay gap were financial advisor, computer programmer, and professor—where median weekly pay was about $400 to $600 higher for men than women. For comparison, some of the jobs with the weakest stereotypes and the smallest difference in pay between men and women were maid, bartender, and cashier.

Stepping out of the ivory tower

The team’s nuanced take on “rational” helps resolve a long-standing debate among scholars about how best to define it.

In the field of economics, for instance, the rational decision-maker is typically seen as a cold and calculating individual who maximizes self-interest. But others in psychology instead prefer to view rationality as fundamentally about cooperation with others. The current study sidesteps such arguments by teasing out how people are using the word in the everyday world.

“There is a tremendous utility in stepping out of our ivory tower and thinking about how these concepts are actually used and grounded in how people actually talk,” Charlesworth says. “In fact, by doing that, we found out that, in some sense, both sides have been right; the average person is using both kinds of definitions interchangeably and frequently.”

Collectively, the findings offer other important lessons for organizations and workers as well.

When companies discuss their values or what kind of employees to hire, the concept of rational and rationality is bound to arise. It’s crucial in those moments for leaders to recognize that being rational is about more than just being logical and analytical; it’s also about being conscientious and trustworthy, Charlesworth says.

“If you’re in a company or an occupation, think about how you’re valuing both attributes of rationality,” she adds. “And think about how you can upweight the interpersonal dimensions of rationality as well, given that they seem to be correlated with jobs that have lower gender–earnings gaps and more representation of women.”

Workers and job seekers can also benefit from understanding the full scope of what it means to be rational. Leaning into both the logical, analytical side as well as the trustworthy, interpersonal side of being rational can open the door to more opportunities.

“The two different definitions of rational have different roles to play in society, but we’re seeing that both can be valued, both are important,” Charlesworth says. “So it’s critical to think about how to ensure that we are framing ourselves, our roles, and our companies in both ways.”

Abraham Kim is the senior research editor of Kellogg Insight.

Dorison, Charles, and Tessa Charlesworth. 2025. “What Is Rationality, Whom Is It Ascribed to, and Why Does It Matter? Evidence from Internet Text for 66 Social Groups and 101 Occupations.” Psychological Science.