Entrepreneurship Strategy Oct 5, 2015

When to Pass the Hat

Strategic timing can help startups get the most from their fundraising.

istock.com/enisaksoy

New venture funding is not what it used to be. It’s not that money from family and friends has dried up, or that angel investors have stopped angel investing.

But having spent more than two decades as a serial entrepreneur and venture capitalist, Joe Dwyer has seen changes to the funding life cycle that can make it tougher than ever for entrepreneurs to stay afloat.

“Many times entrepreneurs are living hand to mouth,” says Dwyer, an adjunct lecturer in innovation and entrepreneurship at the Kellogg School and a partner at Founder Equity and Digital Intent. “They’re constantly fundraising.”

And so, Dwyer argues, it is more important than ever for entrepreneurs get their timing right when seeking funding.

Picking Winners by the Finish Line

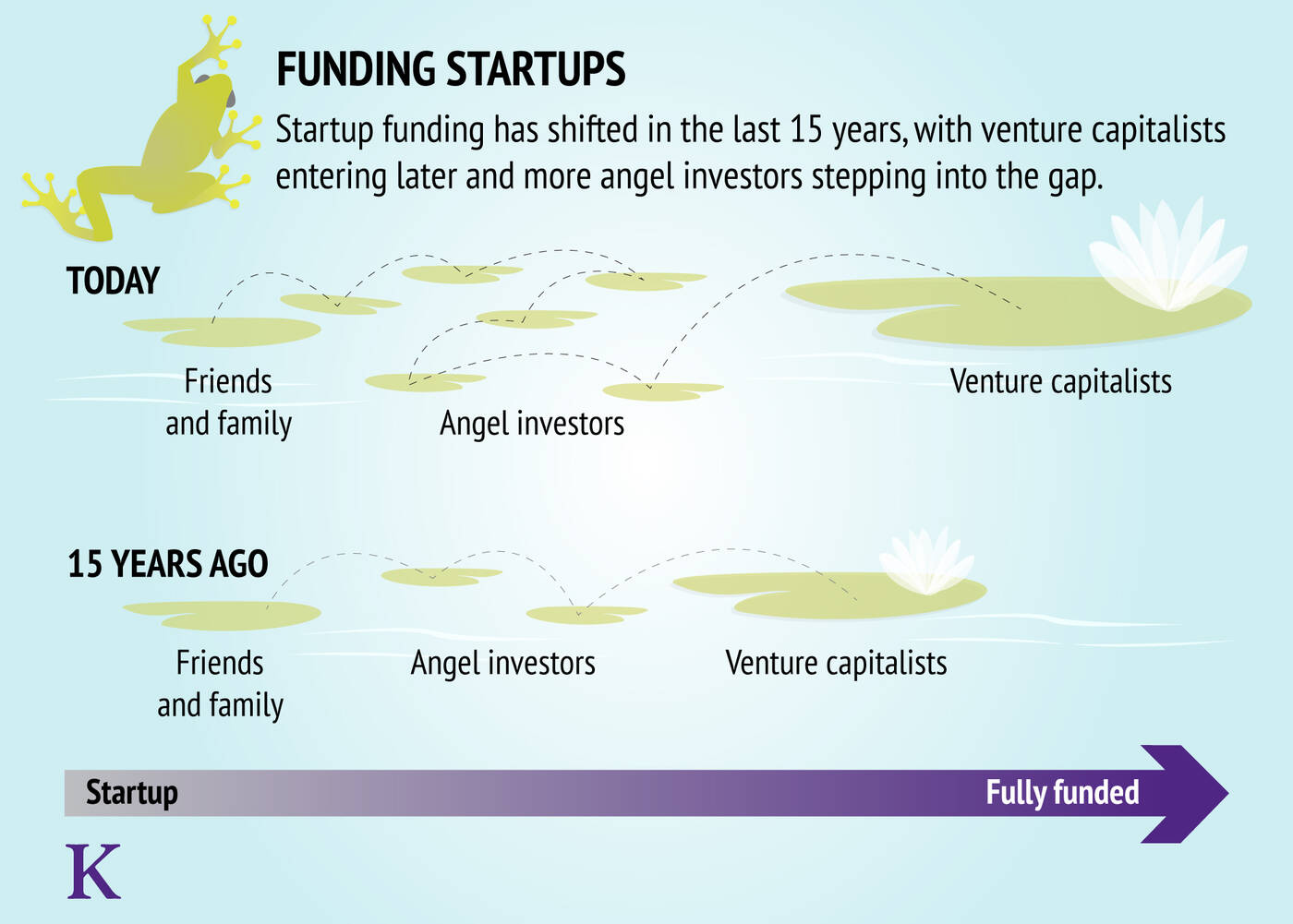

It used to be that the whole idea of venture capital was high risk, high reward, with money being invested to help companies stabilize and scale. But a new trend has emerged in the last two decades, where venture capitalists are waiting until later in the risk curve to make larger investments in the companies that are showing the most promise. Dwyer compares this to picking the winners of the race just before the finish line, rather than when all the runners are still in the blocks.

“The trend towards increasingly large venture capital funds is not just in the aggregate size of the fund, but in the amount of dollars per partner,” Dwyer says. “When more dollars are allocated to each partner to invest, they don’t magically find more great deals, or do more efficient diligence. They’re usually just putting more dollars to work in the same number of investments.”

Part of the reason venture capital funding has moved later in the risk curve is that investors often lack the time and resources to devote to understanding the complexity of some businesses, Dwyer says. So investors wait to see how those companies suss out, which is rational, but problematic for the startups.

Many venture capitalists are also holding out until companies reach the break-even point. “That’s not what you’d normally expect to hear from a venture capitalist, right? Yet it is all too common these days.”

With venture capitalists unable or unwilling—and a little bit of both perhaps—to invest in riskier businesses that typically characterized venture capital investments prior to the last 10 or 15 years, Dwyer says, “there’s a shift in allocation, and I think somewhat of a misallocation.”

That trend has opened up a hole in the market, which has largely been filled by angel investors, some of which are organizing into quasi-institutional “seed venture” funds. This multilayered funding environment is obviously helpful for companies, but with venture capital entering the game later, many companies have to seek round after round of angel funding, passing the hat almost constantly in their middle stages.

Surviving the “Innovation Wasteland”

Though harder to come by, access to capital is no less pressing. Even if a company is frugal, successful operations demand increasing resources. “Suddenly, you’re faced with this challenge of saying, ‘We’re growing, it’s working, and now I need to go get more money.’ You think at that point you’d have relatively easy access to capital from professional investors, but unfortunately, that’s not always the case.”

“We call it the innovation wasteland,” Dwyer says. “You’re alive and kicking, moving forward, and making some real value, but nobody seems be willing to pay attention to you.”

This makes when companies go about raising capital so important. Dwyer offers three tips for entrepreneurs who want to nail their timing.

Define the Measurable Parts of the Business. There is already plenty of uncertainty—and often a fair amount of bluster—involved in any startup. Establishing realistic and consistent measurables is critically important to demonstrating to investors that the company can combine a vision for the future with a view into the current reality.

Most critically, investors will want to understand the fundamental unit economics of the business—so learn them inside and out. “Far too many entrepreneurs have no idea about some of the basic economics, and that’s not a good sign,” Dwyer says. “Early-stage entrepreneurship is about turning uncertainty into risk. If you can’t put numbers to every aspect of the business, it’s very hard to put the level of risk in a box. So if you cannot come in and explain the fundamental unit economics of your startup to an investor, you don’t deserve funding.”

Fundraise Around Milestones. Timing fundraising around measurable milestones—when the business is accomplishing a calculable reduction in risk or uncertainty—can maximize the efficiency of that fundraising.

“Because you’ve proven something, there’s a recent and abrupt increase in the value of your company,” Dwyer says.

Dwyer recommends aligning entrepreneurial and innovation activities around milestones that are both externally and internally visible. That allows a company to plan operations—making sure there is enough money in the bank to pull the milestone off—and fundraising—timing the next round of fundraising to capitalize on the momentum generated by the win.

Give Yourself a Cushion. Finally, companies should avoid cutting it too close when it comes to fundraising. Market cycles, funding environments, the departure of a key team member, or a blip in any area of design or production can wreak havoc on scheduling—and fundraising—plans.

“Don’t go fundraise when you need money or else,” Dwyer says. “You should allot six months to fundraising, because if you don’t have the money to last those six months, you’re going to put yourself in a pretty awkward place.”

Every company should also have a plan in case funding dries up or never arrives—a rainy day fund or an exit fund.

“It’s tempting not to keep a cushion because you’re going to optimize your own economic returns potentially by waiting to get money until you’ve made as much progress as possible,” Dwyer says. “But you’re also taking a risk when you do that. I would say, don’t jump off the cliff without a parachute.”