Finance & Accounting Jan 1, 2024

Who Pays for All Those Generous Credit-Card Rewards?

A new study investigates where this “free” money is coming from—and why credit-card companies are so keen to dole it out.

Riley Mann

You’ve probably seen ads for credit cards offering all kinds of enticing goodies: cash rewards for purchases, access to fancy airport hotel lounges, points for hotel stays, and more. If you’re lucky enough to have one of these cards in your wallet, the 1.5 percent cash back probably feels like pennies from heaven.

But where is this “free” money really coming from, and why are credit-card companies so eager to dole it out?

These are two of the questions Lulu Wang, an assistant professor of finance at Kellogg, investigates in a new paper. The research focuses on so-called payment networks—companies such as Visa, MasterCard, and American Express that set the rules, fees, and rewards for credit cards.

Wang finds that networks are using rewards to compete for customers—and funding those perks by increasing the fees they require merchants to pay. Merchants are left holding the bag and, in response, pass their increased costs on to consumers. In other words, credit-card freebies are costing us all, regardless of how we choose to pay.

“The overarching theme of the paper is that payment networks in the U.S. are competing primarily for consumers,” Wang says. “So if you really wanted to make the market more efficient, you somehow need to control the competition for consumers.”

Wang’s study uses mathematical modeling to test several commonly proposed methods of doing just that. Introducing new private networks to compete with Visa, MasterCard, and the like would be actively detrimental, he finds, and government-sponsored networks would have little effect on the market. But capping merchant fees, as well as encouraging more debit-card usage, would be “the most robust policy,” Wang says.

Behind a simple swipe, a complex system

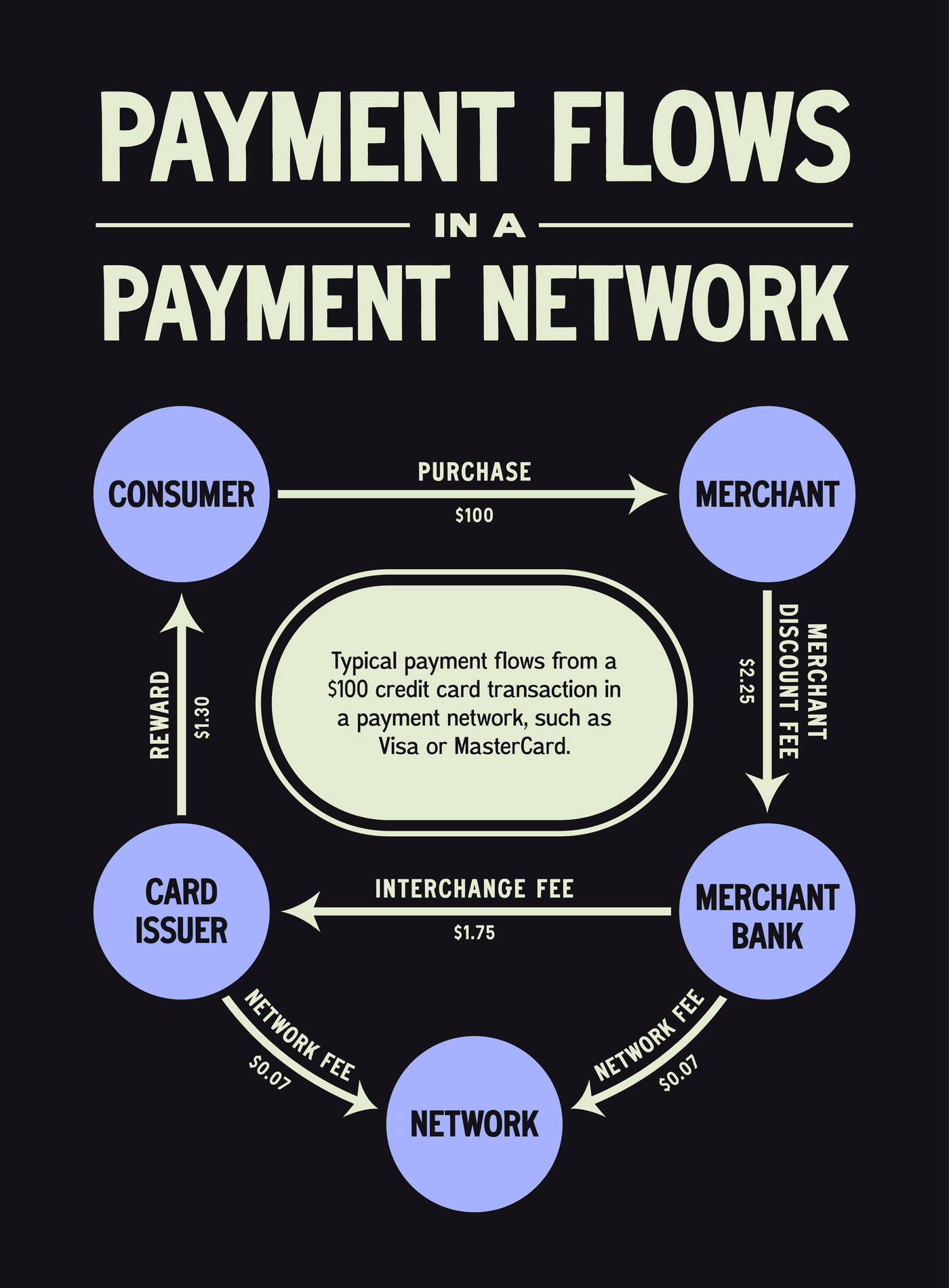

Every time you tap or swipe a credit card, the seemingly simple action triggers a flow of money among several parties:

- The consumer

- The merchant

- The merchant bank, also called an acquirer (either a bank or a company like Square that offers point-of-sale software)

- The network (Visa, MasterCard, American Express, Discovery)

- The consumer’s card issuer (either a bank or, in the case of American Express and Discovery, the network itself)

When a customer pays with a credit card, the store must pay a fee to its merchant bank to process the transaction. The merchant bank, in turn, pays a fee to the network and a fee to the card issuer called an “interchange fee.” The issuer, meanwhile, pays its own fee to the network and delivers rewards to the consumer—rewards funded by interchange fees. Both merchant fees and interchange fees are set by the network; while many countries cap these fees, the United States does not.

Why customers love credit-card rewards—and merchants don’t

To understand the credit-card landscape, Wang gathered data on all these players—consumers, merchants, acquirers, issuers, and networks—from sources including the Federal Reserve and Nielsen.

His analysis revealed two important things: merchants are fee-insensitive, while consumers are rewards-sensitive. In other words, consumers pick credit cards (and, indirectly, networks) based on the goodies they receive, and stores will grudgingly tolerate high fees in order to accept credit cards.

Why? Wang finds that an average merchant’s sales increase around 30 percent from accepting cards. U.S. merchant fees, meanwhile, currently sit at about 2.2 percent, on average. That’s extremely high by global standards, but for most American stores, the exchange is still worth it—pay 2.2 percent for each transaction, boost sales by 30 percent. “The merchants are crying about the merchant fees, but they’re still paying them,” Wang says.

Consumers, meanwhile, have lots of choices about how to pay: cash, debit cards, and a wealth of credit-card options. As a result, “there’s a lot of effort to compete to get on top of wallet for consumers,” Wang explains. Hence all those goodies—throw in airline miles and generous cash back rewards, and you’ll quickly become the preferred card.

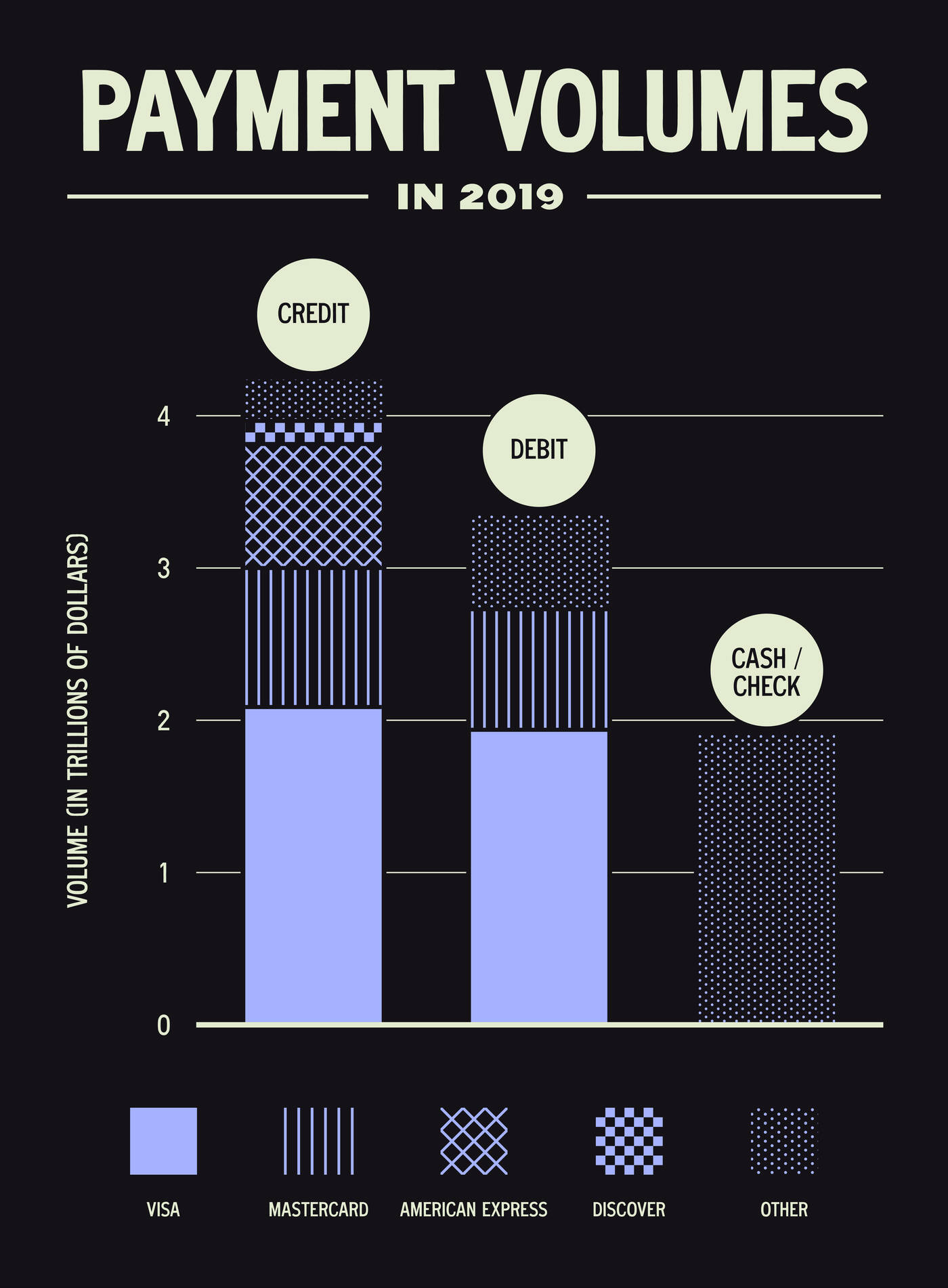

The decline of debit-card rewards demonstrates just how important such perks are in the fight to attain “top of wallet” status. In 2011, Congress passed the Durbin Amendment to the Dodd-Frank Act, which caps interchange fees on debit-card transactions. Not surprisingly, after the passage of this legislation, debit-card rewards programs declined dramatically.

Wang’s analysis reveals that the loss of debit-card rewards led to a 30 percent decline in debit-card payment volumes and a corresponding increase in credit-card payment volumes. In other words, by making it harder for debit cards to compete with credit cards on rewards, the Durbin Amendment shifted some consumer spending from debit to credit.

And incentivizing credit card spending isn’t necessarily desirable, given that many consumers prefer the simplicity of debit cards and fear the risks of credit cards. “Credit aversion,” as Wang calls it, is widespread—and understandable, given the very real financial dangers of credit card debt. Nonetheless, “our current system really encourages a lot of use of credit cards, relative to debit cards,” he says.

Thanks to this combination of consumers being rewards-sensitive and merchants being fee-insensitive, networks have a strong incentive to hike up merchant and interchange fees to fund generous rewards programs. Merchants, then, carry the most direct burden—but Wang argues that burden is getting passed on to consumers, one way or another.

Faced with higher fees, merchants can either raise prices or simply eat the cost—and businesses (especially small businesses) that choose to absorb fees are more likely to struggle and close. “Consumers also take a hit from that, even if it isn’t in the prices of goods that they’re buying,” Wang says. “There’s one fewer coffee shop to go to or one fewer nice seller of clarinets.”

It’s also worth remembering that lots of Americans don’t have incomes or credit scores that provide access to the most desirable credit cards. This means that debit-card and cash users, who tend to be lower income, are essentially paying for the credit rewards enjoyed by wealthier Americans.

Easing the burden on merchants and consumers

So, can the system be improved?

Wang developed a mathematical model to test how different interventions would change the credit-card landscape. He measured what’s called total welfare—a combination of what’s good for networks, consumers, and merchants. Wang’s model assumes customers have multiple cards to choose from, merchants can choose whether to accept cards, and networks compete to become the customer’s preferred card.

First, he modeled what would happen if the government passed regulation capping merchant fees at 1 percent. With less money to fund rewards, credit-card usage would fall, Wang found, and debit card and cash usage would increase. The change would reduce network profits but benefit consumers and merchants; total welfare would increase by $29 billion.

“Our current system really encourages a lot of use of credit cards, relative to debit cards.”

—

Lulu Wang

Repealing the Durbin Amendment’s cap on debit-card interchange fees would also be beneficial, Wang found, to the tune of about $7 billion. Without the Durbin Amendment, debit cards could once again compete with credit cards on rewards. While merchants would not benefit much in this scenario, credit-averse consumers would.

Introducing a new private payment network to compete with Visa, MasterCard, and the like would only make matters worse, Wang found. With yet more networks competing for customers, the incentives to raise fees and increase rewards would only grow stronger; total welfare would decrease by $4 billion. A public-network option would struggle to compete against the private behemoths already in the market and increase total welfare only very modestly, by about $2 billion, the model revealed.

Is there a right way to pay?

Capping merchant fees and repealing the Durbin Amendment are up to Congress. But what about consumers who have and like rewards credit cards? How should they think about the money they are receiving?

There are no easy answers here, Wang says.

“The rational consumer response is, do whatever makes sense for your own financial health and get the rewards if you want,” he says. “The ethicist might say something like, would you be willing to put $100 in your pocket by stealing a penny from 10,000 people?”

Moral concerns aside, there are other reasons customers might choose to eschew rewards credit cards, despite the enticing benefits.

“Nobody ever got rich through credit-card rewards, yet lives have been ruined due to credit-card debt,” Wang says. Sticking with a debit card, which comes with many fewer risks, “I think it’s totally reasonable for lots of consumers.”

Susie Allen is the senior research editor of Kellogg Insight.

Wang, Lulu. 2023. “Regulating Competing Networks.” Working paper.