Mar 1, 2012

How good are sports talent scouts anyway?

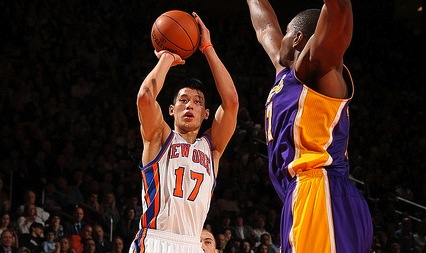

The Jeremy Lin success story has many questioning the ability of scouts and teams to pick the best talent, especially in the NBA. Jonah Lehrer wrote a piece a couple of weeks ago that was a stinging indictment of the “meritocracy” that he says professional sports purports to be. He cites a study that shows NFL teams barely do better than chance alone would predict in selecting top talent.

I sent the article to Blake McShane, an assistant professor of marketing who has studied baseball statistics. We should cut scouts and the draft process some slack, he said. “It is hard enough to predict future athletic performance at a given level of play. It is thus even far harder to predict performance when moving from one level of play to another.”

Countless players have stumbled as they moved from, say, college to the pros. Take Tony Mandarich. The Green Bay Packers drafted Mandarich in the first round in 1989 as the second pick overall, behind Troy Aikman and ahead of Barry Sanders. Hopes were high—Mandarich was an outstanding player in college, and the Packers needed a boost. Plus, his performance in the scouting combine—one way the NFL evaluates prospects—was singular. “It may have been the finest workout the scouts have ever seen,” George Perles, Mandarich’s former coach at Michigan State, told Sports Illustrated in 1989.

But Mandarich’s subsequent performance for the Packers was underwhelming, to put it mildly. Whereas Aikman and Sanders were star players for their teams, Mandarich mostly played special teams before being cut in 1992.

Part of the problem may be in the way the NFL and NBA cultivate talent. McShane pointed me to an article at Marginal Revolution, quoting at length J.C. Bradbury, an economist who specializes in sports. Baseball may offer a different model, according to Bradbury:

In baseball it’s different. Players play their way up the ladder, and even players who are undrafted can play their way onto teams at low levels of the minor league. At such low levels, the high variance in talent is high like it is in college sports; however, promotions from short-season leagues through Triple-A, allow incremental testing of talent along the way without much risk...

Also, a baseball scout acquaintance, who is very well versed in statistics, tells me that standard baseball performance metrics in college games are virtually useless predictors of performance (this is contrary to an argument made in Moneyball). Even successful college baseball players almost always have to play their way onto the team.

This system is very much unlike football and basketball, where players often play their entire college career at one school. With little fluidity in the market, someone like Jeremy Lin may not have as many chances to break out in basketball as he would if he played baseball.

Photo by DvYang.