Aug 8, 2012

India’s blackout

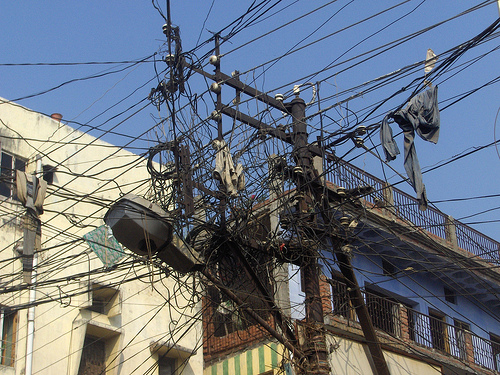

Last week's massive blackout in India put the spotlight on one of the country’s open secrets—its infrastructure is antiquated and crumbling. Over 600 million people in India were without power for days—that’s nearly 1 in 10 people on the planet.

“The fundamental cause is a supply-demand problem. Too much demand, not enough supply, and an inefficient and creaky distribution system,” said Lakshman Krishnamurthi, a professor of marketing.

Rolling blackouts are unfortunately common throughout India. Power grids are built with giant circuit breakers that can be thrown to isolate sections where surging demand could drag down the rest of the grid. The problem in India was, those breakers weren’t thrown. Many people suspect corruption caused this blackout—captured regulators and bureaucrats didn’t intervene when they should have, allowing various constituencies to draw too much power. Apparently this happens all the time in India, just not on this scale. But the ailing grid is ultimately to blame because without its underlying problems, such unscrupulous behavior wouldn’t have had as big of an impact.

The massive blackout has underlined concerns about India’s grid and its ability to effectively manage it. The grid’s unreliability has created massive headaches for businesses. “Most companies operate with backup power supply from diesel generators” not just to deal with blackouts, but frequent power shortages, said Sunil Chopra, a professor of managerial economics and decision science. While that means many companies were relatively unaffected by the blackout (save for employees unable to get to work because of the gridlock), it doesn’t mean electricity shortages haven’t taken their toll. Having to invest in expensive infrastructure like generators “often raises the cost of doing business,” Chopra pointed out.

Though Indian companies have long had to contend with electricity shortages, this blackout will undoubtedly pose new challenges. Investors may shy away from the country, fearing the unreliability of its grid. “In the short-term it will definitely be a negative,” Chopra said. “The long-term impact will depend on the response of the government, which currently controls most of the generation capacity.”

But, he added, “If this event serves as a wakeup call, it could be good in the long-term.”

India’s grid may ultimately become a bottleneck for growth. “To achieve sustained growth rates of 8% over the next 10 years, the country’s infrastructure problems have to be addressed,” Krishnamurthi said. “Energy is the prime driver of economic growth.”

What’s driving the supply shortage is multifarious. Transmission and distribution losses in India are over 20 percent, Krishnamurthi said. For reference, losses in the U.S. grid are about 7 percent. India’s estimated losses might be on the conservative side, too. Electricity theft by households and business is not uncommon, he added. Plus, India is heavily reliant on hydroelectric power, and the north has not received much rain this year. Coal-fired plants haven’t been able to make up the difference because of coal production shortages, Chopra and Krishnamurthi both pointed out.

“In the long-term, the solution is to increase supply,” Chopra said. “In the short-term, demand has to be managed with supply being rationed.”

Photo by daviddumas.