Featured Faculty

Senior Fellow and Adjunct Professor in the Kellogg Executive Leadership Institute

Michael Meier

It’s been a season of harrowing news for U.S. cybersecurity. In December, we learned that a group of hackers—almost certainly Russian agents—infiltrated SolarWinds, a Texas-based IT firm, granting it access to nine federal agencies and a growing list of private companies. Then, in March, another breach: this time it was Microsoft, which announced that Chinese hackers had exploited vulnerabilities in their Exchange email servers, compromising hundreds of thousands of organizations’ data. Add to this the ransomware attack in May that caused the disruption of the largest energy-pipeline system serving the East Coast.

These cyberattacks have unnerved experts because of their size and scope, but also because the first two were launched from within the United States itself—on servers run by Amazon and GoDaddy, among others—allowing the hackers to bypass the government’s warning systems, which are legally prohibited from surveilling domestic networks. (It was FireEye, a private firm, and not the U.S. government cybersecurity organizations tasked with the defense of networks or identifying the activities of cyber actors—like the DHS, FBI, NSA, or U.S. Cyber Command—that discovered the breach at SolarWinds.)

The attacks have led some to reconsider the relationship between government and industry when it comes to protecting against future attacks.

“What this shows is that you can’t build a strategy around ‘the government will take care of itself, and the private sector will take care of itself, with some level of collaboration between the two,’” says Mike Rogers, a retired four-star admiral who led U.S. Cyber Command and the National Security Agency. “That has largely been the strategy to date, but that approach isn’t optimal, and our adversaries are taking advantage. They’re adapting, and we’re not keeping up.”

President Biden recently announced an executive order mandating that any software vendor that serves government agencies must adopt a range of security measures, including data encryption and multifactor authentication. They must also immediately notify the federal government of any breaches.

For Rogers, a senior fellow at Kellogg, this is a good start, but there’s still plenty that could be done to bolster cybersecurity across the public and private sectors. “It’s not about collaboration,” he says. “It’s about integration. The only way to defend ourselves in real time is to work together 24/7. That way, as either party comes up with potential cyber activity, we can respond in real time, not weeks or months later.” In the case of SolarWinds, the hackers were in the networks for nine months before they were detected.

So what should businesses leaders understand about their role in this new era of enhanced cyber-vulnerability?

Here are four lessons they can draw in light of the recent threats.

Having served as a commander in charge of the Department of Defense’s cybersecurity operations, Rogers sees a number of lessons business leaders might draw from the military’s experience. But ultimately, they boil down to this: be proactive.

“Don’t assume that a nation state has no interest in targeting you—they’ll target anyone they believe has something of value to them, and you may also become an unintended victim,” Rogers says.

Given the amount of risk involved, it’s critical for organizations to deliberately and methodically think through how they can protect themselves and how they’ll respond if they believe they have been targeted. “In the military, we would invest time, resources, and personnel to anticipate potential threats. We’d perform regular exercises, simulating a state actor penetrating our networks, testing for vulnerabilities. Our motto was ‘plans are nothing, planning is everything,’” he says.

Exactly what such exercises or simulations might look like will differ from one organization to the next. But a good step for all companies is to create a culture of accountability.

“It’s amazing how accountability can influence people’s behavior,” he says. “And since cybersecurity is everyone’s issue, it’s important that leaders and organizations hold themselves accountable for protecting critical networks.”

In part, this means that all leaders—even those who are not tech savvy—need to take responsibility for guarding against significant hacks.

“I sometimes hear my peers say, ‘I just don’t know much about cyber.’ But you’d never hear a CEO or a Board member say that about finance—even if that they had never been a CFO. Nobody would ever say, ‘Hey, I’m not a money guy.’ It’s the same way with cybersecurity,” he says. “Its fundamental to the way every company works.”

A key part of being proactive is knowing your digital supply chains. Just as a toxic product can make its way through a physical supply chain, corrupted code can have an enormous ripple effect.

It’s important to recognize that hackers are “using the very structure of the internet against itself,” says Rogers.

“We don’t tend to think about software when we think about supply chains, but it’s clear we’re going to have to.”

— Mike Rogers

Consider the regular software update, which is what hackers exploited in the SolarWinds breach. By corrupting the code of SolarWinds’ software update, the hackers were able to spy on client companies like FireEye as well as large swathes of the U.S. government, including the Department of Homeland Security.

“We created this whole system with the idea that downloading software was a good thing—it increases functionality, security. Our ability to download software whenever and wherever we want is central to our economy. The problem is that also means that everyone’s potentially at increased risk—and business leaders should recognize that.”

This makes it increasingly important for companies to be cognizant of which vendors they are partnering with, and what products they are downloading.

“Supply chains take on a whole different meaning in this hyperconnected digital world,” Rogers says. “You want to be sure controls are in place to avoid corruptions or viruses all along the chain. Where are you getting your software? Who’s writing it? Who’s verifying it? Where is it coming from? We don’t tend to think about software when we think about supply chains, but it’s clear we’re going to have to.”

It would also behoove companies to spend more time assessing threats to their operational technology. With more firms automating parts of their manufacturing process and expanding their ability to remotely access parts of their infrastructure and production lines, there’s a growing dependence on having to secure this from exploitation.

Last year, Honda was blindsided by a major ransomware attack that disrupted internal computer networks and shut down global production lines. And there’s growing concern that criminals or state actors will continue to threaten factories and power grids or energy distribution.

“The more functionality you automate, the more risk you take on,” Rogers says.

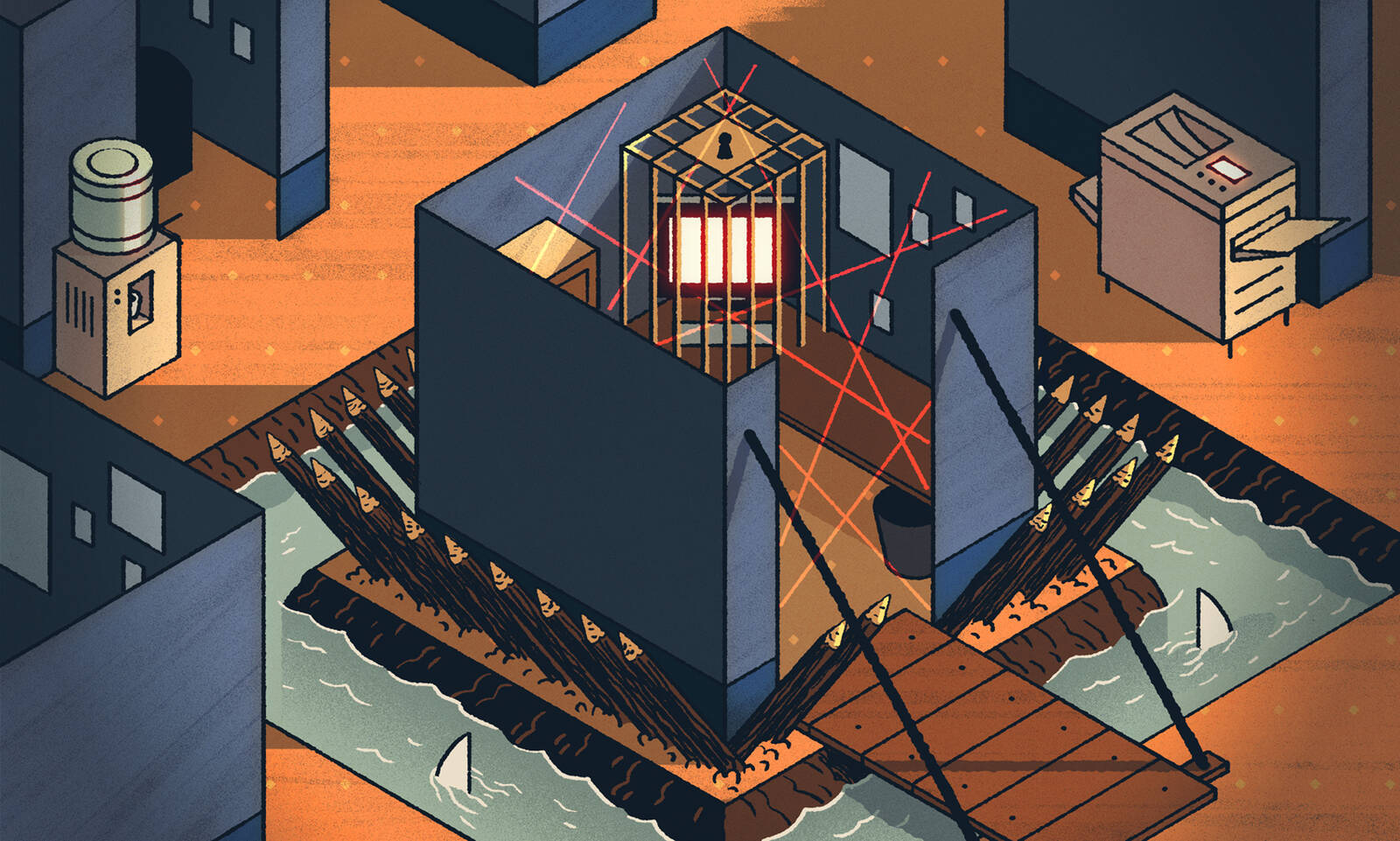

In the past, cybersecurity was designed as if to protect a castle. The goal was to keep the network safe behind high walls and deep moats—in other words, to “secure” the perimeter.

Today this is nearly impossible, in part because of the sheer number of devices connected to each network, and in part because, after COVID, we have all grown more comfortable with accessing work data from home.

“We’ve blown up the perimeter,” Rogers says, “and our digital footprint is now a blur between business and personal life. This is further exacerbated by the ‘internet of things’ and the drive towards more connectivity.”

Given there’s now a better chance that an adversary will “get inside” an organization’s network, companies should focus more on building “cyber-resilience”: processes and mechanisms that allow them to keep functioning in the event of an intrusion.

For example, companies should make updates to their networks randomly and quietly, making it more difficult for adversaries to anticipate their cybersecurity activities. Other steps for increasing resiliency include having a current and accurate understanding of the network topology; aggressively monitoring activity on the network; building backups and redundancy for critical infrastructure; and minimizing the connections between the business segment and operational segments within the company’s IT structure.

And, of course, companies will also need to have a detailed process in place that allows people—including the leadership team—to respond quickly if confronted with a cyber event.

“The Defense Department can’t shut down for a week to secure its network, and most businesses can’t either,” Rogers says. “So a good strategy will involve not just walls and moats, but a nimble defense in the event someone gains unauthorized access.”

One of the major challenges with improving cybersecurity is that companies often don’t want to admit they’ve been compromised. But cooperation across industries is essential for protecting against attacks.

“Even as they compete with each other, companies need to partner in areas that represent a major risk to their industry as a whole,” Rogers says, pointing to the example of banks in the wake of the financial crisis.

Here is where the government might be able to play an important role in managing cybersecurity risks, just as it has for many years in managing aviation safety. As a nation, we’ve decided that the risk of injury or loss of life from aviation accidents justifies the existence of a government agency, the NTSB, whose job it is to investigate the cause of any aviation accident to determine what caused the accident and then identify the actions necessary to ensure it never happens again. After a crash, an airline or the aircraft manufacturer can’t pretend it didn’t happen or not acknowledge the event, citing proprietary information, or chalk it up to bad luck. In each case, all the parties involved must share company data, training and personnel records, and the maintenance history of the plane. Regulators must also be granted access to the crash site.

“There’s a reason why aviation mishaps don’t tend to recur,” Rogers says. “They tend to be unique incidents, and that’s because there are constant changes and updates to safety protocols, manufacturing standards, software configurations, training requirements, and maintenance protocols.”

In this sense, the NTSB is one potential model for future cybersecurity efforts. But businesses will need to accept the trade-off between protecting their networks and sharing information. The price of corporate reticence is that industries don’t learn the details of how exactly a hack was conducted, which means the same nefarious actors can keep using the same techniques.

“How many major cyber events will it take before we decide to make fundamental change?” Rogers says. “We have to overcome this challenge, or we’ll keep having these major events.”

Andrew Warren is a writer based in Los Angeles.