Featured Faculty

SC Johnson Chair in Global Marketing; Professor of Marketing; Professor of Psychology, Weinberg College of Arts & Sciences (Courtesy)

Michael Meier

Police shootings of unarmed black men have become increasingly scrutinized in recent years. With that scrutiny has come a frequent demand that officer activity be videotaped, whether with body cameras or dashboard cameras in squad cars.

The goal of this footage, of course, is to provide impartial evidence that could either help exonerate officers or convict them, depending on whether a shooting appears justified on film.

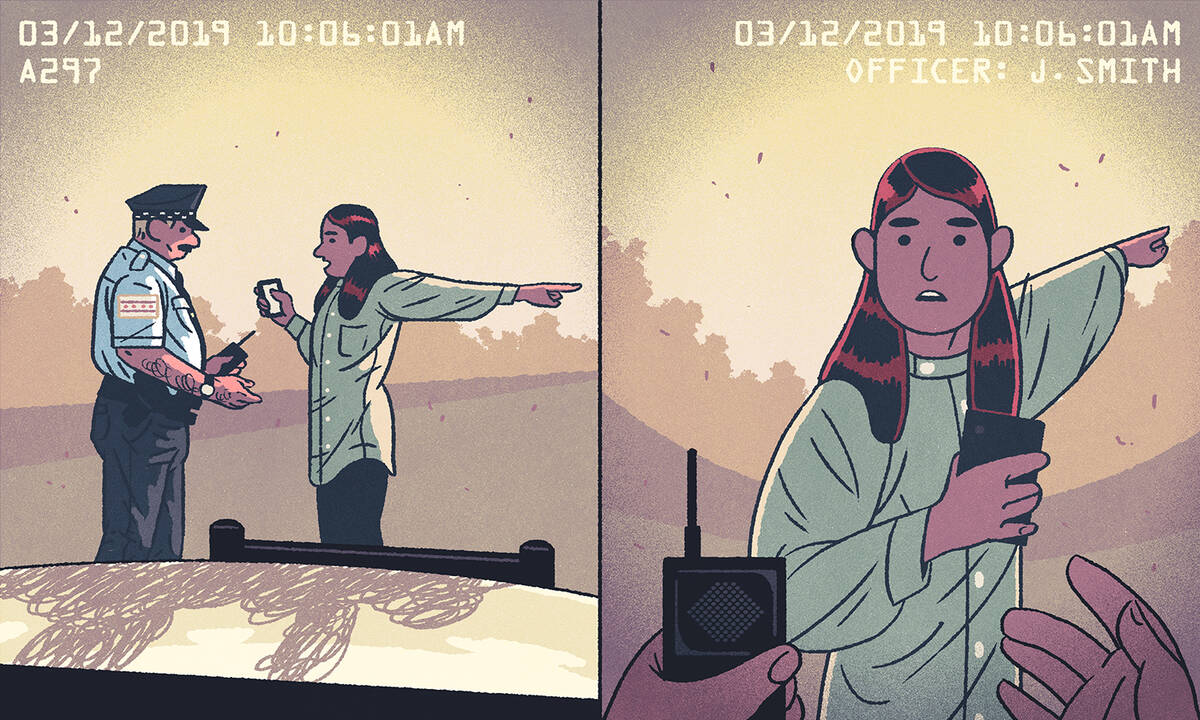

But a team of Kellogg researchers wondered just how impartial such evidence really is. Is all footage equal? Or might jurors perceive interactions filmed by a body cam versus a dash cam differently? And would these differences affect how much they blamed the officer?

“There’s all this pressure to get this technology, and yet no one stopped to ask, ‘What does this all mean?’” says Broderick Turner, a PhD student at Kellogg, who conducted research with Neal Roese, a professor of marketing at Kellogg, to get at that answer.

They found that people who watched a body cam version of an interaction—anything from the wearer bumping into someone to a police shooting—were less likely to believe that the person instigating that action did it on purpose, as compared to people who saw the same interaction filmed by a dash cam.

There was a “diminished sense of blame or responsibility for the person who’s wearing the body cam,” Roese says.

This is an important distinction, especially if charges are filed against an officer. Intentionality, Roese says, is “the difference between first-degree murder and manslaughter.”

The researchers recommend filming interactions from more than one point of view—for instance, from dash cams and body cams on multiple officers—so that jurors aren’t biased by seeing just one perspective.

“Whenever possible, I think more video is better,” Roese says. Installing body cams “is the beginning of a process of reaching greater accountability, but it’s not the end.”

Turner’s interest in this research topic arose in part from witnessing the surge of surveillance in today’s society, from security cameras to bystander iPhone videos. And he has a personal investment in understanding how video footage affects our perceptions of police shootings.

“I’m a huge black dude. I’m 6’6” and 250 pounds on a good day,” he says. “I am personally concerned about police activities. I care about Black Lives Matter.”

Turner and Roese were surprised that they couldn’t find any research on whether viewers interpreted these body cam vs. dash cam perspectives differently. After all, a body cam presents a first-person perspective. Typically worn on the chest, it shows what the wearer is seeing. In contrast, a dash cam shows a third-person perspective.

People who saw the body cam footage said the officer was less intentional. And they thought the officer deserved less blame and a weaker punishment.

Consider an incident in which an officer breaks a car window. A body cam would show a close-up of the baton shattering the glass, but not much of the officer herself. A dash cam would show the officer striking the window.

To conduct their own research, Turner and Roese teamed up with Eugene Caruso, at UCLA’s Anderson School of Management, and Mike Dilich, a Chicago-based engineer who works in forensic analysis and legal consulting.

To understand these different perspectives, the researchers staged a simple interaction: one man bumping into another man. They filmed the incident from both a body cam on the person who did the bumping and a dash cam-like perspective about 10 feet away.

They then recruited 105 online participants, and showed them one of the filmed versions. Participants rated whether they thought the first person bumped into the second person intentionally, on a scale of 1 to 7.

The dash cam group gave an average intentionality rating of 3.25, while the body cam group rated intentionality at 2.66. A similar experiment that showed videos of an interaction between two women (instead of men) yielded similar results.

The team also performed the same test with real police footage from three incidents: one of an officer breaking a car window and two of an officer shooting a suspect. (Participants were warned about the nature of the videos beforehand to limit their distress.) Again, people who saw the body cam footage said the officer was less intentional. And they thought the officer deserved less blame and a weaker punishment.

What could be causing the difference? The team came up with two possible explanations.

Perhaps viewers take the perspective of the body cam wearer—putting themselves in their shoes, so to speak. Previous studies suggest that people don’t like to blame themselves for bad behavior. So viewers may thus be less likely to think the body cam wearer did something on purpose.

If this explanation was right, then explicitly encouraging participants to take the wearer’s perspective should also change their perceptions of intentionality. That is, it should make those who watch dash cam footage less likely to believe that an officer did something on purpose. And it should make those watching body cam footage rate the officer’s intentionality even lower.

But that’s not what the team found. When they asked some participants to “take the perspective of the police officer” it didn’t make much of a difference, suggesting that perspective-taking wasn’t the key factor driving people’s tendency to blame—or not blame—the officer.

That brought the team to the second hypothesis: Maybe viewers are influenced by the fact that aside from the occasional hand or foot entering the frame, the wearer is largely out of sight. Perhaps the lack of a visible person makes viewers less likely to blame them.

To test this, the researchers deliberately introduced more views of the body cam wearer. They created videos of people performing simple tasks such as knocking over a cup or kicking a trash can. In some body cam videos, the wearer wasn’t visible at all. In others, viewers could see the person’s arm or foot.

“Some people have an uncritical perception that if you bring in body cam footage, in and of itself, it’s going to make things better. ... That may not always be the case.”

— Neal Roese

When participants saw the videos that included glimpses of the wearer’s body, they rated intentionality about as high as those in the dash cam group. “Those judgments basically look exactly the same as those for the dash cam version,” Turner says.

Would this matter in court proceedings? To find out, the team obtained a real police report of an officer breaking a car window. The car’s driver had passed out and the car was stopped in the middle of the street. After being unable to wake the driver by tapping on the window, the officer broke the passenger side window. The surprised driver woke up and accelerated into a power pole, starting a fire.

In a lab experiment, the researchers asked 203 people to read the report. Some participants also viewed body cam or dash cam footage of the incident. Then they had to decide whether the officer should be indicted on several different charges.

Seventy-one percent of dash cam viewers recommended indicting for assault, 69 percent for battery, and 60 percent for aggravated battery. But among body cam viewers, those figures were only 49 percent, 53 percent, and 49 percent, respectively.

Surprisingly, people who read the report without watching any videos were about as likely to indict as the dash cam group. The researchers don’t know why, but they speculate that when people do watch a video, they tend to focus on that and pay less attention to the report.

“Video dominates written words,” Turner says. “It’s almost like the report exists less when there’s a body cam.”

The team is still trying to better understand the differences in perception. For example, what happens if an incident is filmed from yet another perspective, such as a security camera?

What’s clear is that we should not assume that people interpret all video the same way.

“Some people have an uncritical perception that if you bring in body cam footage, in and of itself, it’s going to make things better,” Roese says. “The takeaway from this research is, wait a minute, that may not always be the case.”

Yet body cams are still useful, Turner emphasizes. If several officers at the same incident all wear cameras, that collection of footage provides a variety of perspectives. In essence, he says, “they each become each other’s dash cam.”