Featured Faculty

Previously a member of the Managerial Economics and Decision Sciences Department faculty

Yevgenia Nayberg

There’s an old Kenyan joke about the nation’s roads, which were often built in odd and irrational places and seemed to have little use for actual transportation.

“The joke was that we are so wealthy that these roads are being built to dry our wet clothes,” said Ameet Morjaria, assistant professor of managerial economics and decision sciences at the Kellogg School.

Morjaria grew up in Tanzania and went to boarding school in Kenya. That joke from his youth helped to inspire his recent research. In it, he uses the country’s haphazard road network to investigate the impact of democracy on the unequal distribution of public resources. In particular, he wanted to know whether the system for funding and building roads became less corrupt and biased toward certain groups of people—and thus the placement of roads became more driven by economic reasons —during periods of democracy.

There are five major ethnic groups in Kenya, which British colonial authorities largely segregated into different administrative districts. After gaining independence from Great Britain in the early 1960s, Kenya has experienced alternating periods of autocracy (authoritarian rule) and democracy. Under autocracy, the researchers wondered, did Kenya’s president engage in “ethnic favoritism,” favoring districts dominated by his own ethnic group by giving them more roads?

“If you look at a road map of Kenya from the late 1980s, you literally see roads going nowhere.”

Morjaria and his coauthors report that the form of government did make a difference—indeed, a dramatic difference.

“If you look at a road map of Kenya from the late 1980s, you literally see roads going nowhere,” says Morjaria, who used to pore over such maps as a child. “There’s no economic development and limited population in those areas.”

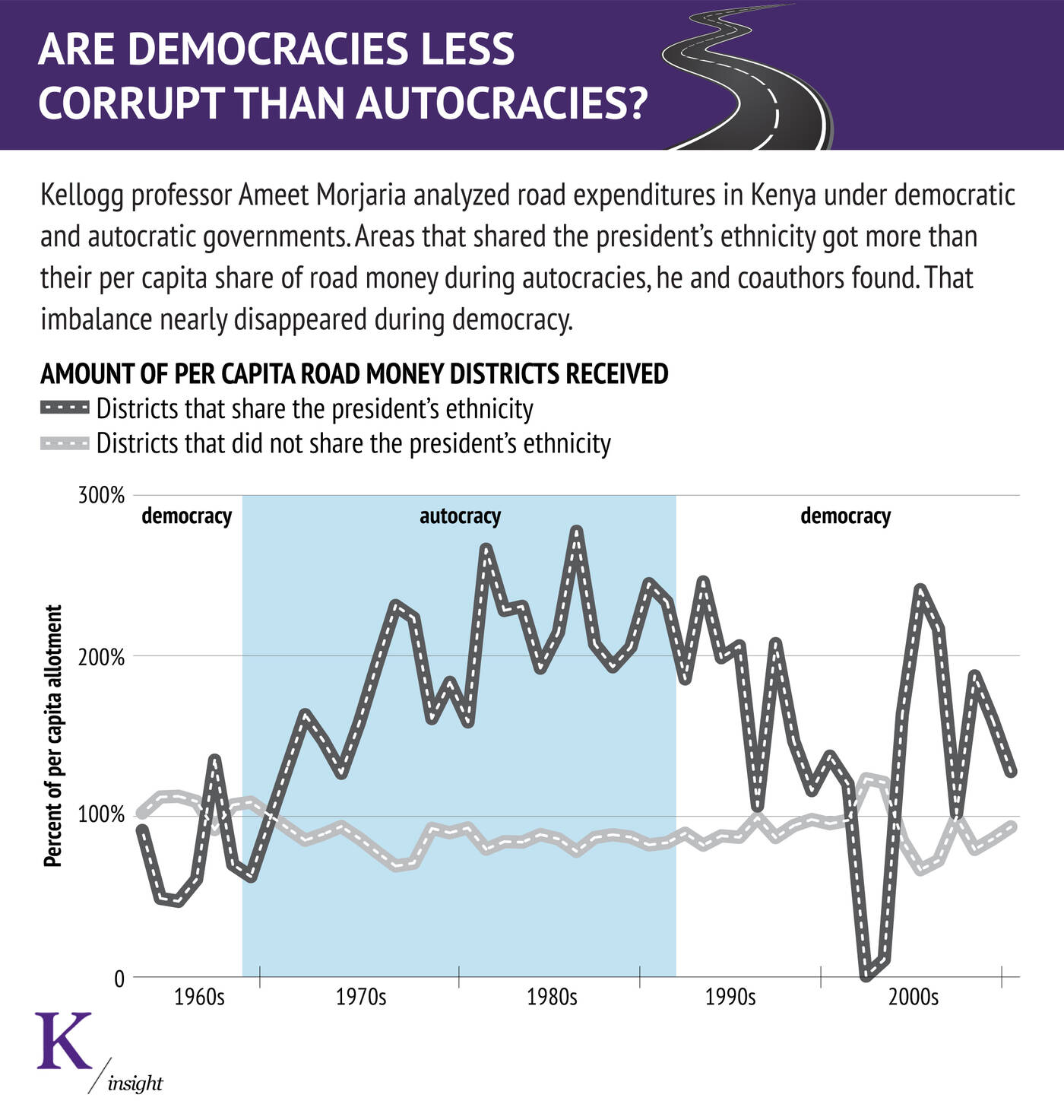

During the years of autocracy—from late 1969 to late 1992—districts that were “coethnic” with the president, meaning they shared his ethnicity, received three times more investment in road-building projects than their population share would deserve. And the length of the roads built in those districts was more than five times their predicted share.

But remarkably, those imbalances almost completely disappeared during the two periods of democracy—1963 to 1969 and 1993 to 2011.

For much of the last half century, Kenya and other African countries have had flat or negative economic growth.

“Africa was basically what they call a growth tragedy,” Morjaria says.

Scholars often point to ethnic favoritism as a key factor in Africa’s growth tragedy, since corruption misallocates resources and can stifle productivity. If favoritism is curbed during democracy, then that could be helping to fuel economic development during those periods.

In the immediate wake of Kenya’s independence, a democratic government came to power, and the economy grew at a strong pace throughout the 1960s. By 1970, GDP per capita growth was about 6 percent.

But in December 1969, an autocratic government assumed power, and GDP per capita growth declined sharply for the following two decades. “You have a period of darkness in the 1970s and 80s and the early 90s, when growth was basically in negative territory,” says Morjaria.

After democracy returned to Kenya in 1992, the country’s economy began to rebound. GDP rose gradually, hovering around 2 percent from the mid-2000s through the end of the decade. Much of sub-Saharan Africa followed a similar pattern of economic growth and stagnation through these decades as their governments alternated between autocracy and democracy. Since the mid-1990s, both economic growth and the number of democracies in Africa have gradually increased.

While the relationship between type of government and economic growth seems apparent anecdotally, hard data has not been easy to come by. Nor has it been easy to find direct evidence of the role of ethnic favoritism in these cycles. So Morjaria, along with Robin Burgess and Gerard Padró i Miquel of the London School of Economics, Remi Jedwab of George Washington University, and Edward Miguel of the University of California-Berkeley, turned to roads.

Part of the reason this research is difficult to tackle is that you need three key, but elusive, elements in place. You need reliable data that show where resources are going, which can be hard to come by in the developing world; you need to study a place that has seen changes in who controls the government, which can be difficult in parts of the world where those in power can become entrenched; and you need a political system that changes as those in power change.

Kenya provides an interesting lab to take on all these challenges.

African institutions that keep reliable records on public expenditure are relatively scarce. But the researchers came up with two innovate ways to tackle this issue in Kenya. There are historical road maps, created periodically by the Michelin tire company, which show the growth of the road system through time. The researchers obtained and digitized these. They also obtained records of government expenditures on road projects. Moreover, roads are the single largest source of public expenditure investment in Kenya—larger than health and education combined.

And unlike most other public projects in the country, roads are funded almost entirely by the central government—a fact that gives the office-bearer a great deal of influence over where they are built.

Roads “occupy a large percentage of the development budget each year,” Morjaria said. “They’re visible. They link people and places and access to markets. So they are a good laboratory” to look at whether democracy curbs corruption, thus perhaps boosting economic growth.

In their study, the researchers created their own hypothetical, economically ideal Kenyan road network for a nearly 40-year period.

They constructed this hypothetical road network by ranking the “market potential” of new roads connecting all 49 major urban areas that existed in Kenya (or just beyond its borders) in 1962. The “market potential” metric takes into account the population of urban centers and the distance between them.

The researchers determined the total length of new roads that had actually been built between the creation of one Michelin map and the next. Then they built their hypothetical network by inserting roads according to their ranking of market potential, stopping when they reached the total length of real roads built in that period. They repeated this process for each Michelin map that was published, roughly one every three years, through 2002.

During the decade of democracy between 1992 and 2002, according to the researchers, the two road systems—actual and hypothetical—look very similar. They look much less similar during autocratic periods.

In particular, roads built during democracy connected the nation’s capital, Nairobi, and other major urban centers “to a wider range of towns and cities, including many that are in districts that never share the ethnicity of the president,” Morjaria says.

Overall, from 1963 to 2011, districts coethnic with the president received twice as many road expenditures than their population share would predict. But this tilt toward coethnic districts was almost entirely a result of investment during autocratic periods, when these districts received three times their predicted share of road expenditures.

The power of democracy to prevent corruption—and perhaps spur economic growth—is good news for African economies broadly, because the trend on the continent is toward democratic governments. The next step for the researchers will be to extend the same sort of analysis they have done in Kenya to the rest of Africa. If Kenya is a representative case, then even imperfect democracies deter cronyism.

“We’re not talking about anything very sophisticated when it comes to the political institutions,” Morjaria said. “We’re simply talking about the ability for people to go and vote, with the option to vote for more than one party.”

“If there is democracy, maybe the effects of ethnicity can be muted, because you have better checks and balances on leaders,” he says.

For example, the researchers note that the decline of ethnic bias in road spending in Kenya under democracy can be attributed, in part, to the fact that reporting on road construction in the nation’s two largest independent daily newspapers increased substantially after democracy returned in December 1992.

“The democracy effect kind of constrains these guys from favoring their own people,” Morjaria says, “simply by having the possibility, albeit a small one, of being kicked out of office.”

Burgess, Robin, Remi Jedwab, Edward Miguel, Ameet Morjaria, and Gerard Padró i Miquel. 2015. “The Value of Democracy: Evidence from Road Building in Kenya.” American Economic Review. 105(6): 1817–51.