Featured Faculty

Professor of Strategy; Herman Smith Research Professor in Hospital and Health Services Management; Director of Healthcare at Kellogg

In the United States, individuals who do not qualify for public health insurance must either find an employer who offers health insurance or make their way on the individual market. The latter, however, is often a prohibitively expensive prospect. Many economists have suggested that this tight linkage between health insurance and employment has led to employment lock, or “the idea that you work solely for the purpose of getting insurance,” explains Craig Garthwaite, an assistant professor of management and strategy at the Kellogg School.

Among other things, the Affordable Care Act (ACA), also known as “Obamacare,” aims to put an end to employment lock. By ensuring that anyone can purchase affordable insurance through state-based exchanges, the legislation allows people to change jobs—or even exit the workforce altogether—without giving up health insurance. In addition, the ACA involves a large expansion of Medicaid that will cover everyone whose income is below 138 percent of the poverty line.

So just how many people are likely to choose to leave the labor market after the ACA’s implementation? “We estimate anywhere from 500,000 to 900,000 people, depending on a range of assumptions,” says Garthwaite.

The Origins of an Estimate

Public health insurance in the United States has generally been reserved for people with incomes that fall under a fixed amount—a feature that might actually serve as an incentive against earning more income. Without a well-functioning non-employer option, someone earning more than that amount could end up uninsured. “Ten thousand dollars a year—let’s say that is the limit. If you earn $10,001, you lose coverage. If you earn $9,999 you still have coverage,” says Garthwaite. “A lot of people won’t earn more than $10,000.”

Under the ACA, however, eligibility for insurance comes with no strict income cutoffs: someone making more money will simply pay more in premiums. Because the ACA works so differently from most American public health programs, its implications have proven difficult for economists to predict.

But though unique, some features of the ACA are not entirely unprecedented. In 1994, Tennessee expanded its public healthcare program TennCare to include anyone—regardless of income—deemed “uninsured and uninsurable,” meaning that they did not currently have access to health insurance and could not get access on the individual market. As with the ACA, the program was free for those with incomes under a fixed amount, while those who earned more paid more.

In 2005, facing rising costs, the state ended its expansion, disenrolling all users who did not qualify for traditional Medicaid. Over a period of just a few months, 170,000 people were kicked off of the state’s insurance rolls.

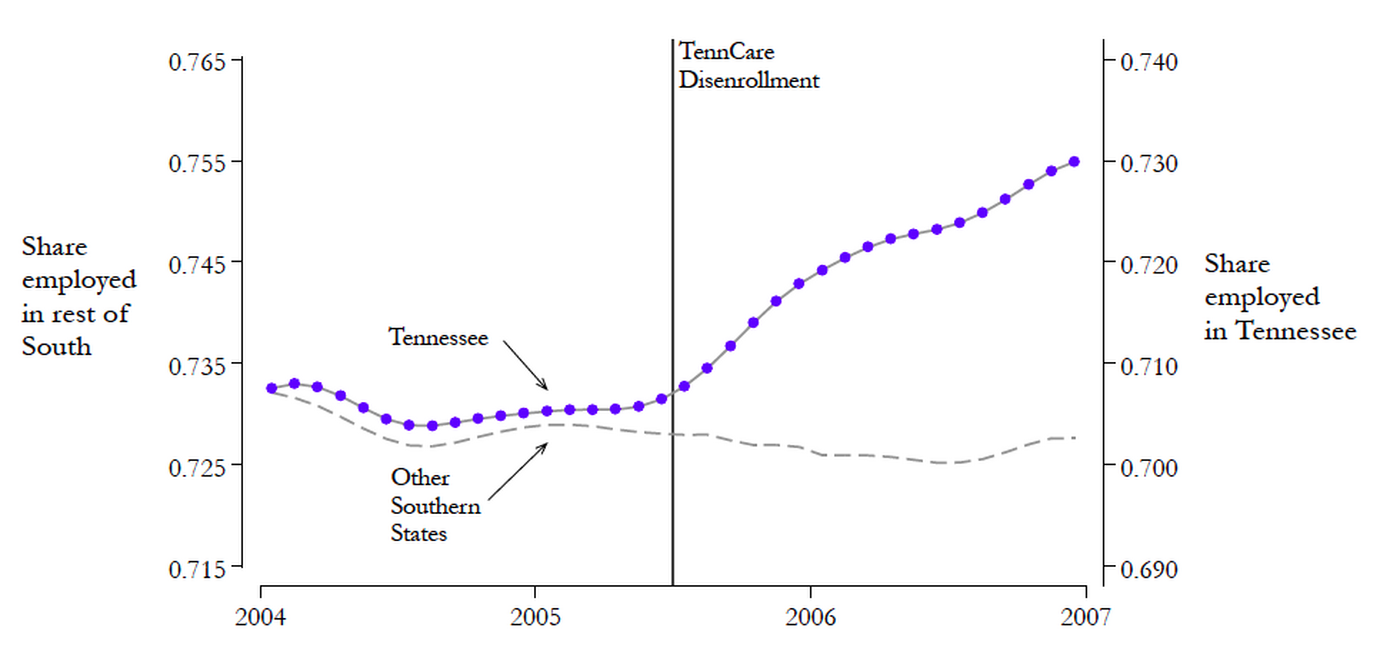

The rise in employment rates cannot be attributed to the region’s economy more broadly.

This contraction, explains Garthwaite, resembles the ACA’s implementation, only in reverse. As such, it provides a good place for Garthwaite—along with his collaborators, Tal Gross of Columbia University and Matthew Notowidigdo of the University of Chicago—to look for answers. “What we do is we look at these people and we say, ‘Well what happened to them?’” says Garthwaite. “That will give us some sense of what might happen when the ACA goes into effect.”

Answers in Tennessee

So what did happen in Tennessee? Garthwaite and his colleagues found that between 2004 and 2006—the two-year period spanning the TennCare disenrollment—Tennessee’s overall employment rate increased by 2.6 percentage points.

That rate increased to 4.6 percentage points for childless adults, the demographic disproportionately affected by the cuts. Comparisons with other populations, including adults with children in Tennessee (who were less affected by the cuts) and adults with and without children in other southern states, suggest that the rise in employment rates cannot be attributed to, say, the region’s economy more broadly. This and other evidence—including a spike in the Google search term “job openings” in Tennessee during the two months after the cuts to TennCare—seem to point the finger squarely at the loss of public health insurance.

In all, Garthwaite explains, “about half” of the childless adults cut from TennCare obtained private health insurance within a matter of months—many by entering the labor force. The researchers estimate that it would take an approximately 26% increase in wages to generate a similar increase in the size of the labor force. For many of the disenrolled individuals, the cost of employer-provided healthcare amounted to roughly that percentage of their income.

As you might expect, however, the researchers found evidence that not all disenrollees valued health insurance equally. Although older adults—those above 40 but not yet eligible for Medicare—and younger adults lost access to public health insurance at roughly the same rate, “it’s mainly the 40- to 65-year-olds who are really moving into the insurance market. Those are people who probably have much higher expected use,” said Garthwaite.

Implications for Obamacare

Finally, the researchers applied lessons learned from Tennessee to estimate the likely effects of the ACA. They calculated how many American adults making less than 200% of the poverty line—the population most affected during the TennCare expansion and cuts—were currently working with access to employer-provided health insurance. They then determined, using estimates from Tennessee, the number of employment-locked Americans who would likely choose to leave the labor force if given another way to obtain affordable health insurance: between 500,000 and 900,000, or about 0.3 to 0.6 percent of the workforce.

“This is not any comment on labor demand or ‘job killing’ or anything like that,” Garthwaite is quick to note. “This is a choice by people: Once we open up the market to non-employer-based insurance, how are you going to choose to make your labor–leisure trade-off?”

So should we be worried that this exodus from the labor market is bad news for the country’s productivity? Not necessarily, says Garthwaite. Freed from employment lock, some people might, of course, do nothing at all. But other individuals might move into volunteer work, go back to school, invest in other personal development, or engage in any number of activities. “There are a lot of productive things for the country you could do that aren’t work. And so we shouldn’t think of this as bad for America in that sense. We should think of it as people now having an option they didn’t use to have.”

Garthwaite, Craig, Tall Gross, and Matthew J. Notowidigdo. 2013. “Public Health Insurance, Labor Supply, and Employment Lock.” NBER Working Paper No. 19220.