Marketing Nov 2, 2016

How Millennials Are Discovering Music

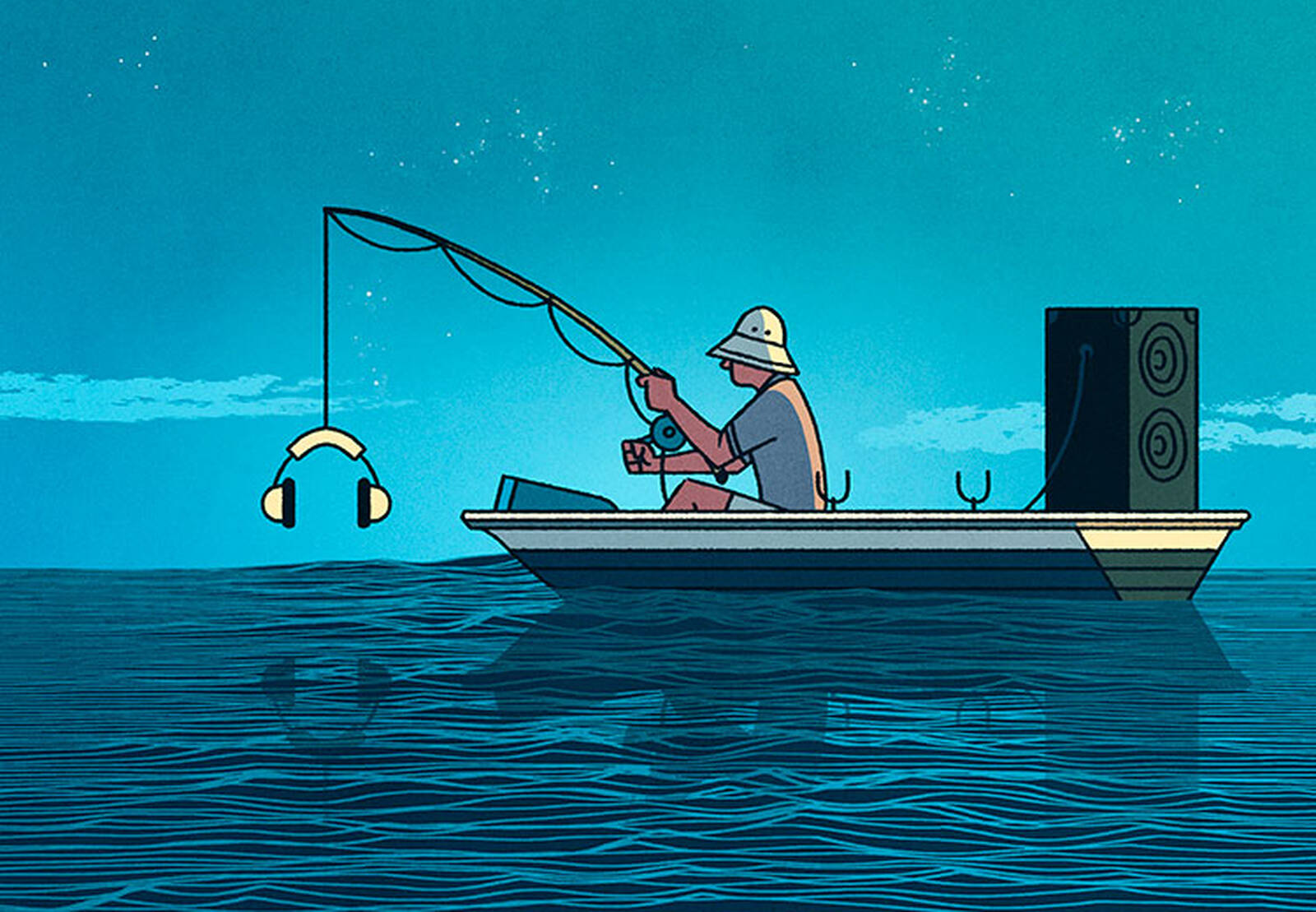

To woo listeners, music platforms should get personal.

Michael Meier

How do millennials discover new music?

Online music platforms are eager to learn the answer in order to draw in millennials, who have disposable income and tastes that have not yet crystallized.

“It’s a little bit easier to appease the older generations who aren’t investing as much time into new music,” says Libby Koerbel, a recent Kellogg School MBA graduate and now a strategist at Pandora, who queried millennial music listeners under the guidance of Marketing Professor Kent Grayson. Their goal: provide music industry leaders with a deep understanding of the discovery process for this demographic.

In addition to surveying 1500 people, Koerbel conducted in-depth interviews. The resulting conclusions, Grayson says, “come with the authority of actually having sat down with millennial listeners and asked them.”

So what should music industry leaders understand about millennials?

1. Active listeners fit three types.

Koerbel’s interviews identify three distinct listener groups among millennials: “routinists” who enjoy hearing music that they already know; “backstorians” who have narrow tastes but are intensely interested in the artists they like; and “songsmiths” who connect emotionally with songs through their sound and lyrics rather than a particular artist or genre.

For platforms, knowing which type of user you are trying to appease can impact new features you want to showcase.

“Backstorians, for example, are really interested in this other content beyond the music,” Koerbel says. “Right now, most services only have a little artist bio page, and half the time the bio isn’t even filled out!” Integrating artist videos, personal photos, Tweets, or other updates into a streaming platform could represent a huge opportunity.

Platforms looking to appeal to songsmiths, on the other hand, might consider going beyond predictive recommendation systems that tend to favor more of the same content—great for routinists, less so for songsmiths—and instead consider more hands-on curation to delight users with new music that pushes the boundaries of a songsmith’s taste profile.

2. Attracting listeners requires fulfilling a specific need. Retaining them will require more.

Among all groups, the most popular ways to consume music is via YouTube, Pandora, and traditional radio.

“Regardless of what you are looking for out of music, or what your motivation is for discovering new music, those services are ubiquitous because they’re fulfilling a specific need,” says Koerbel.

She describes YouTube as “Google for music”—a place where people can access any song on demand. Pandora is the platform of choice for background listening—at work, at parties, when hanging out with friends, or when getting ready to go out. And radio? For car rides, of course. Surprisingly, radio still is used by a majority of millennials who are looking for a convenient way to listen to music in the car that will not drain their data packages.

“At the moment, platforms can’t do both acquisition and retention really well.” - Kent Grayson

The convenience that digital platforms offer directly addresses the current focus of the industry: achieving scale.

“Given the content costs and the costs of running the business, the only way to make money is to have as many people on your platform as possible,” Koerbel says. “Platforms are more valuable to the music industry if they can say, ‘I have over 80 million monthly active users in the U.S., and I can tell advertisers about their listening behavior.’ In order to do that, people are trying to appeal to everyone, which can be a downfall for a lot of these services.”

But keeping those listeners over the longer term will be a different, more complicated, step.

“At the moment, platforms can’t do both acquisition and retention really well,” Grayson says. “Some can try, and maybe as platforms develop, the bigger ones will start with one and then get good at the other.”

Part of the problem is the ease with which listeners can abandon ship as soon as one platform no longer meets their needs, or another provides a more engaging, novel experience.

“A lot of these services fill a need in the moment, like, ‘Oh I want to listen to this song, or I want some music to elevate my mood,’” Koerbel says. “I think the struggle is then giving the listener more variety in their experience, whether that’s in the type of music or the way it is delivered.”

3. Consider an “adventure dial.”

To provide this variety, platforms might consider encouraging more user interactivity. “What’s missing in current platforms is the place for input that feels really natural,” she says. “These listeners are people that actively invest time in music. They’re not going to be as easily scared away by more interaction. But there’s never an adventure dial, to say, ‘Today I’m feeling adventurous. Why don’t you give me something random or cool?’”

Interactivity would also address the reality that, no matter which overall segment a listener falls into, her motivations for listening will change from day to day.

To illustrate the downside of assuming consumer intent, Koerbel shares a story about trying to purchase an e-book for an upcoming vacation. Online, she was shown recommendations based only on her previous ordering history. The problem? “The books I’d been downloading the last three months had been for my classes, and now I’m going to the beach, so I’m in a different circle now. The site keeps trying to push me business books, and I’m tired of reading business books,” says Koerbel.

4. Segmentation should not be set in stone.

Some of the most obvious takeaways for the music industry—personalization, variability in the user experience, and the opportunity to provide more robust input—are likely to be costly for platforms to adopt. They may also complicate the user experience.

“You develop a product that is perfect for people in one segment and it is likely to be imperfect for someone else,” says Grayson.

Additional bells and whistles could intimidate a more casual listener—while efforts to customize the listening experience for some audience segments—artist paraphernalia for the backstorians, for instance—may come across as irrelevant, or worse, to songsmiths.That is, if routinists, backstorians, and songsmiths are still the most relevant audience segments by the time these features become available.

“The question of segments is one of the biggest questions that any company can answer,” Grayson says. “How many segments should we use to define the market? How refined should we be? Competition comes in, the world changes, new products are introduced, and the way that you’ve defined your segment starts to have less value.”

Think of the current descriptions that emerged from the survey as a snapshot of today, he says. “Companies can stick too long with what they learned two years ago without updating. That decision might make them vulnerable to a competitor.”