Featured Faculty

Max McGraw Chair in Management and the Environment; Professor of Management & Organizations; Senior Associate Dean of Strategy and Academics

Michael Meier

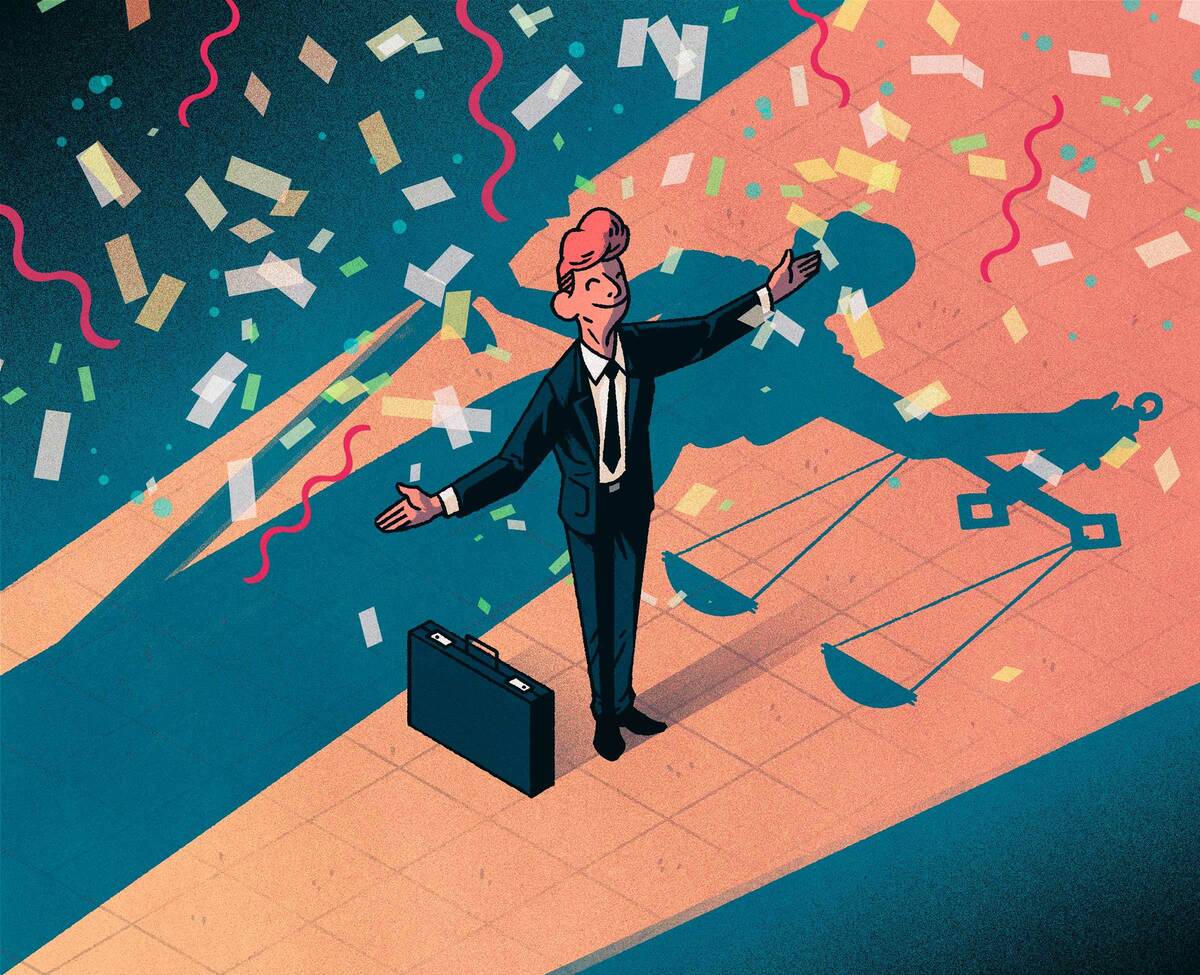

For companies facing employment discrimination lawsuits, prestige can be a friend or foe.

According to new research from Brayden King at the Kellogg School, when a prestigious company faces accusations of employment discrimination, it enjoys the benefit of the doubt. In the eyes of the jury, its high status can help protect it from blame.

But when a company is found liable, the research found that the company is punished much more harshly than less prestigious firms.

This could have implications for both companies and employees, says King, a professor of management and organizations. Such cases are widespread: the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission receives nearly 100,000 discrimination accusations per year.

King, who is interested in how businesses are held accountable in society, had previously found contradictory results on the effects of prestige. Prestigious companies, for example, were more likely to be the target of activist groups, even when less prestigious companies acted worse.

“Prestige is harmful to organizations in that it draws attention to their potential hypocrisy,” he says. “These companies are supposed to be standout examples of virtue in their industries or examples of how companies should behave. It makes them high-profile targets.”

But, when King studied prestige among Major League Baseball pitchers, he found that high-status pitchers who had reputations for accurate pitches received more favorable calls from umpires.

To further understand how prestige is helpful or harmful in holding businesses accountable, King turned to employment discrimination lawsuits. King worked with Mary-Hunter McDonnell, a former Kellogg Ph.D. student who is now an assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania. She is also a former law professor and had a hunch that prestige gave companies the upper hand in court.

“People don’t think about the role that social and psychological biases play in trials,” McDonnell says. “They think of litigation outcomes as a function of the talent of the litigators or the strength of the evidence. But our research shows otherwise.”

To build a dataset of high- and low-status companies, the researchers looked to the 826 companies that were surveyed for Fortune’s Most Admirable Companies list between 1998 and 2008. Each of the companies was given a score between 0 and 10. For the sake of the study, the researchers defined low-prestige companies as those near the bottom of the rankings and high-prestige companies as those near the top.

They also looked specifically at these companies’ reputations in diversity and employee relations through the Kinder, Lydenberg, Domini & Co. Statistical Tool for Analysis of Trends, which ranks firms’ strengths and weaknesses in these areas.

The positive expectations associated with prestige led juries to give these companies the benefit of the doubt.

When the researchers compared the list of high- and low-prestige companies to an employment discrimination lawsuit database, they found 519 employment discrimination cases involving these companies that went to a jury. Of those, 238 cases resulted in a verdict of liability and a subsequent damages award to the employee.

The researchers found that during the initial trial, high-status organizations benefited from a “halo effect”: the positive expectations associated with prestige led juries to give these companies the benefit of the doubt. Juries were 14 percent less likely to find these companies liable compared to low-status firms.

But if a high-status organization was found liable, it faced a “halo tax”: it was punished much more severely. Juries awarded the victims of high-status firms as much as three times more in punitive damages compared to low-status firms. That’s likely because research shows that high-status companies are held to a higher standard, and when they act improperly, they are seen as hypocritical, King says.

“If there is uncertainty whether an organization is to blame for something, then prestige will benefit that organization,” King says. “But if it is clearly established that they acted wrongly, prestige works against them.”

The study found several other effects of prestige on employment discrimination outcomes.

Interestingly, companies that had previously been involved in discrimination suits faced less punitive damages. That is likely because, unlike with individual offenders who go on trial, juries in these trials do not take the idea of being a repeat offender into account.

“If you have a criminal record, you will be punished more harshly,” McDonnell says. “We found it works differently for organizations. Juries don’t make the same character attributions to chronically deviant organizations. They think about organizations differently.”

This could be because juries do not view repeat-offender organizations as a single entity, but rather a collection of individual offenders. That, McDonnell says, is unfortunate, since firms can have a culture that enables this sort of behavior. “It’s an organization-level problem that’s leading to repeat conduct,” she says.

The research also found that firms that are headquartered in the state where the trial is happening are less likely to be found liable—a home-court advantage, so to speak. Additionally, firms face higher punitive damages when the trial involves racial discrimination or when the employee is female, compared to cases that do not involve racial discrimination or when the employee is male.

The firm’s reputation as a good employer—which is a separate measure from prestige—had no effect on whether companies were found liable, but it did result in a somewhat higher damages award if the companies were found liable.

The implication for high-status firms is clear: push the boundaries and you may be given the benefit of the doubt, but you also run the risk of being punished more severely.

Given the value of prestige and reputation, and given the fact that prestigious firms are more likely to be targets for lawsuits, it may not be worth it for companies to engage in behavior that puts themselves at risk.

“Firms don’t like uncertainty,” McDonnell says. “They will do their best to mitigate the likelihood that they will be dragged into court.”

But employees considering bringing a discrimination suit against a prestigious employer must also know what they’re up against.

“Employees have to know they are facing constraints,” King says. “There are these intangible benefits of status and prestige that benefit the company over them. If you stack everything together, it means employees are at a real disadvantage.”

The researchers plan to study the effects of these lawsuits.

“What are the effects on a company’s status if it is consistently found liable in these lawsuits?” King says. “Companies want to avoid being cast as bad actors, and they are very protective of their overall reputations, but we haven’t been able to quantify the impact that these violations have on their status later on. That’s what we want to find out.”