Featured Faculty

Sandy & Morton Goldman Professor of Entrepreneurial Studies in Marketing; Professor of Marketing

Yevgenia Nayberg

It is human nature to want to see ourselves as the heroes of our own story. So, in ways large and small, we work hard to maintain a positive self-image. Indeed, research has shown that one way we do this is by actively avoiding comparisons with people who are similar to us but who also possess negative characteristics.

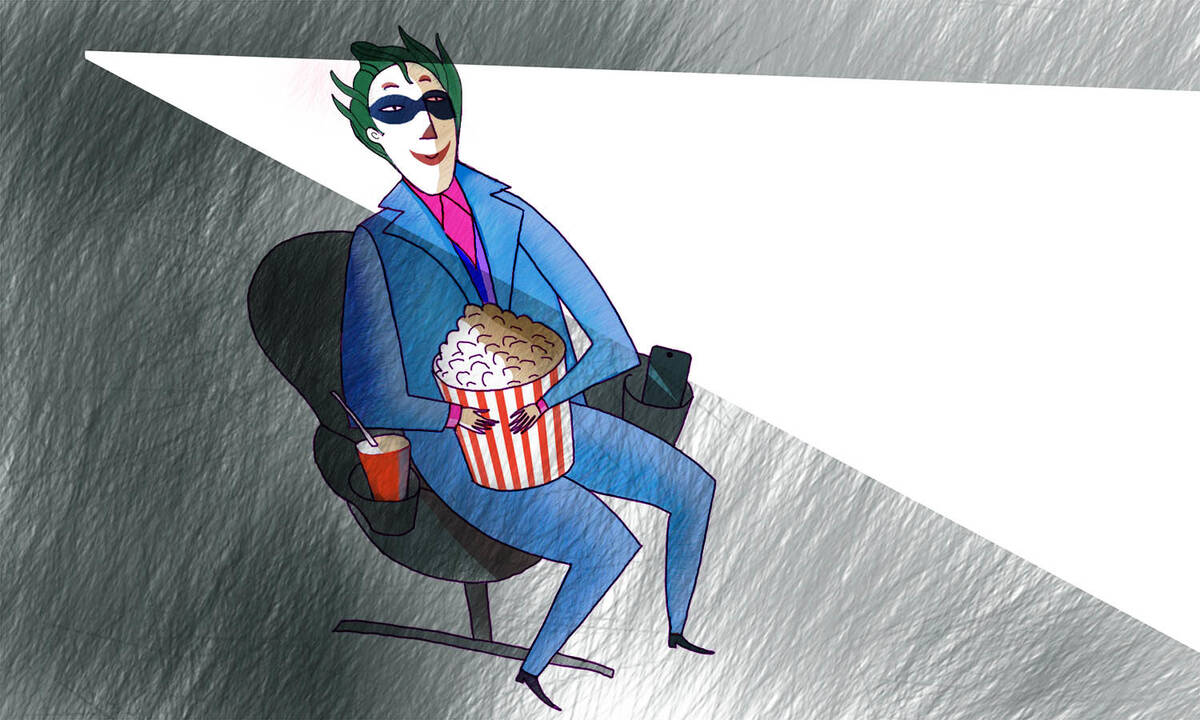

Yet, new research from the Kellogg School of Management suggests one context in which we are surprisingly willing to explore our darker selves: the world of fictional villains.

This research, conducted by Derek Rucker, a professor of marketing, and graduate student Rebecca Krause, suggests that, unlike with real villains, when fictional villains are more similar to us, we actually feel more attracted to them.

The research began with questions about what consumers prefer when it comes to characters in books and movies. “Characters are important parts of the entertainment industry,” Rucker says. “We gain value from being able to connect with the characters, and marketing efforts often feature heroes and villains.”

Based on prior research in psychology, companies might decide to avoid drawing attention to the similarities between, say, moviegoers and villains for fear that those comparisons would produce avoidance and disengagement among the public, Rucker explains. “Yet, our research suggests this might not be true.”

The researchers were initially surprised by their results, Krause says, but also intrigued. “We began exploring the crucial follow-up question: Why?”

The researchers suggest that, within the safe confines of fantasy, we’re able to explore our dark side without fear of negative consequences. Books, movies, and TV “provide enough of a safe haven that you’re no longer worried about the potential downsides of the comparison,” Krause says. At that point, a familiar pattern kicks in: “Similarity provokes interest.”

To understand whether people relate to villainous characters, the researchers began with data from CharacTour, an entertainment discovery platform founded by Kellogg alumna Kimberly Foerster (’98). Foerster, the company’s CEO, notes, “CharacTour was born out of an unmet consumer need: to connect users in a very personal way to the characters they would most enjoy in movies, TV shows, books, and video games.”

CharacTour’s unique platform features profiles for more than 5,500 fictional characters, and allows users to become a fan of the various heroes, villains, and sidekicks—similar to “liking” a page on Facebook.

Each registered user takes an interactive quiz in which they self-describe their individual personality traits. They then receive a custom feed with personality-based entertainment recommendations, as well as their matches to characters who are most similar to them. For example, they may discover they are a 94.6% match to Sherlock Holmes.

“Villains provide an interesting window into learning about parts of the self that we don’t normally explore.”

— Rebecca Krause

In order to match users to characters, the CharacTour team assesses characters’ personality traits on a numerical continuum and uses natural-language-processing techniques to analyze character-specific dialogue in scripts. Having these data on the characters allowed Rucker and Krause to run detailed analyses of how CharacTour’s roughly 232,000 registered users related to the heroes and villains in their database. Specifically, they were able to quantify how many fans each character had and how many of those fans reported possessing personal traits shared by that character. These data allowed the researchers to determine how users’ similarity to various heroes and villains affected their attraction to them.

Based on prior research, one might have expected that people would feel attracted to heroes like them but distance themselves from similar villains. That is, as a character’s score on a trait, such as “optimistic” or “cynical,” increased, the percent of their fans who have that same trait should increase for heroes but decrease for villains.

Yet, their analysis upended that view. As a character’s score on a trait increased, the percentage of that character’s fans who shared the trait increased too—a pattern that held true for both heroes and villains.

“We thought people would stray from similar villains, and instead we found they were brought to them,” Rucker says.

For Foerster, this indicates that “the ideal of perfection is not something that resonates with everyone. Certain consumers may find messaging that addresses their imperfections and darker sides more compelling. For example, heroes are often the front-and-center of movie and TV show posters. But additional marketing efforts around a story’s villain could potentially attract even more viewers to a new title.”

It is clear from the CharacTour data that, in the real world, people do not always behave the same way as they do in specific laboratory environments. The next step for Rucker and Krause was to figure out why that might be.

They suspected it had to do with the protections provided by the fictional world. Similarity to a fictional villain is likely to feel less harmful to our self-image than similarity to a real one: it’s much less distressing to be compared to the Riddler than to Hitler.

To test this idea, the researchers recruited 100 university students to complete an online study. Participants saw brief descriptions of fourteen quizzes. The list included four that the researchers were actually interested in. These were about which individual—fictional villain, real-life villain, fictional hero, or real-life hero—participants most resembled.

We are surprisingly willing to explore our darker selves in the world of fictional villains.

After seeing each quiz description, participants were asked to rate, from one to seven, how likely it was that someone might be made uncomfortable by the results of the quiz. (The researchers framed the question this way on purpose: participants might be too sheepish to say they would feel uncomfortable about something as insignificant as the results of an online quiz, but would be more likely to acknowledge that someone else could feel uncomfortable.)

The results showed that the prospect of taking a quiz about fiction was more comfortable than taking one about real-life. Crucially, taking a quiz about similarity to a fictional villain was less uncomfortable (an average of 3.81 out of seven) than a real-life villain (an average of 4.92 out of seven).

The researchers designed another study to further test whether people’s attraction to fictional villains could be explained by the safety of stories. Namely, if stories supply safety, then removing that sense of safety should remove people’s attraction to similar villains. So, they designed an experiment that would make stories feel less socially safe to participants.

The researchers recruited 397 participants and divided them into two groups.

They prompted one group to feel that stories were not, in fact, a domain protected from social judgement. They did this by having participants read a report based on real research stating that people who are similar in one way are likely to be similar in other ways. (The coded message: if someone notices that you and a movie villain are both, say, very punctual, they might assume you also share the villain’s penchant for demeaning others.)

Then this group, which the researchers labeled the “threat” group, was told they would be rating their interest in watching a particular movie in the context of a first date—a scenario likely to make them feel concerned about how they might be perceived by their crush.

The second group, the “threat absent” group, did not read the scientific report, and was told they would be rating their interest in watching that particular movie alone.

Next, before they provided their rating, participants in both groups saw one of two text messages, which researchers said was sent by a close friend. In all cases, the text message described the film as enjoyable to watch. For a subset of the participants, the text also stated that the villain, Sam, was uncannily similar to them.

Finally, as they’d been prepped earlier, participants were asked to rate from one to seven how interested they were in watching the film, as well as how similar they felt to the villainous Sam.

By making stories feel unsafe to some participants, the researchers were able to reverse the trend they’d seen in earlier studies. Specifically, in the threat group, participants who were told Sam was similar to them were less likely to express interest in watching the movie (2.77 out of seven) than those who were only told the movie was good (3.40 out of seven). Meanwhile, in the threat-absent condition, being told that they were similar to the movie villain somewhat increased participants’ interest in seeing the movie (4.42), as compared to only being told the movie was good (3.99).

For the researchers, this experiment had two takeaways: first, it offered additional evidence that one reason we allow ourselves to contemplate our similarity to villains in fiction, but not in real life, is that stories feel safe—specifically, safe from the judgement of our peers.

“The evidence we have collected gives us confidence that we really understand the reasons behind both the repulsion from and attraction toward villains in different contexts,” Krause says.

It also showed how strong our interest in similar characters really is.

“It took a lot to turn off the similarity effect,” Rucker says—the context of the date, the text from the friend, and the research report. “The allure of similarity was stronger than we anticipated.”

Beyond the takeaways for marketers—maybe they should sometimes put villains front and center in some campaigns—Rucker and Krause are intrigued by some of the deeper questions the findings raise, such as: Why do we feel drawn to our dark doppelgangers?

It’s something they didn’t explicitly address in the paper, but the authors have a few ideas.

“One reason is that similarity is inherently attractive,” Krause says. “It creates a common base for understanding and learning. The other factor is that villains provide an interesting window into learning about parts of the self that we don’t normally explore.”

After all, it can be fun to be rebellious and transgressive, and fictional villains allow us to explore those sides of ourselves—without the real-world consequences. “A lot of people who are actually good human beings,” Rucker says, “who would never want to be bad in the real world, may see fantasy as a means to entertain it.”