Featured Faculty

James J. O'Connor Professor of Managerial Economics and Decision Sciences; (Center) Co-Director of the Global Poverty Research Lab (GPRL)

Lisa Röper

In the 1920s, a doctor named Albert Johnston had trouble finding a medical residency. Johnston was biracial, with Black ancestry, and hospitals at the time often did not permit Black physicians to treat white patients. But when a Maine hospital allowed him to apply without specifying his race, Johnston finally secured a position. He and his wife Thyra, who was one-eighth Black, started a new life as a white couple.

Johnston’s decision was an example of “passing”: identifying as a different race. During the Jim Crow era, when Black people were systematically denied opportunities and lived under the threat of lynching, some who were able to pass chose to do so in order to avoid the economic, physical, and social injustices of the time. And while historians and biographers have documented many instances of passing, researchers have not had a clear idea of how common this behavior was.

“The big question is, can we quantify this?” says Ricardo Dahis, a PhD student in economics at Northwestern University, who coauthored a study on this topic with Nancy Qian, a professor of managerial economics and decision sciences at Kellogg, and Emily Nix at the University of Southern California’s Marshall School of Business.

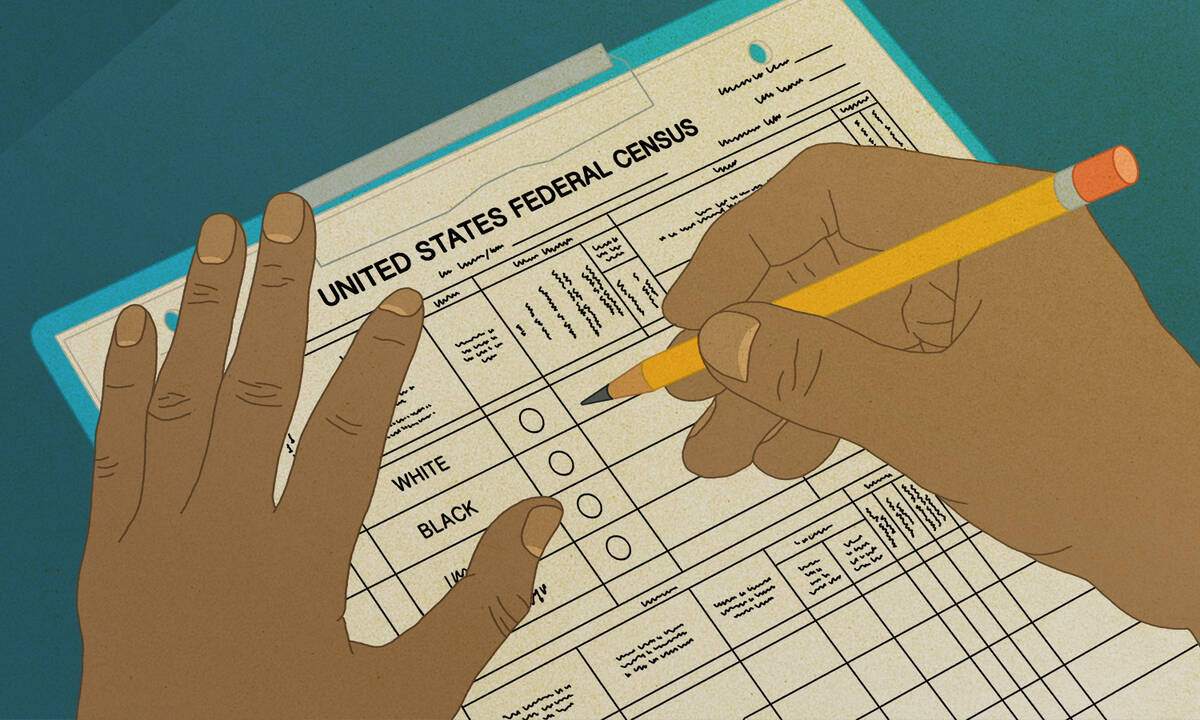

To come up with numbers, the researchers searched detailed U.S. census records taken from 1880 to 1940. They were able to thus track specific people through time and note if their race changed from one census to the next. (Women were too difficult to track because they usually changed their last names after marriage.) The team estimated that, on average, at least 1.4 percent of Black men under age 55 started passing as white per decade, adding up to more than 300,000 men over the study period. However, the estimate is very conservative, and the actual rate could be as high as 7–10 percent, the researchers say.

Men who passed often moved to other counties or states. Census records suggest that in some cases, the men passed without their Black wives or children; in others, the entire family may have passed as white.

“Racial discrimination was so extreme that in order to escape it, people redefined themselves,” Qian says. “They changed their own identity.”

The motivation for why Black men might have wanted to pass is painfully understandable.

From 1877 to 1950, white supremacists lynched more than 4,000 Black people in the South. Those who managed to avoid violence were blocked from better schools or higher-ranking jobs because of their race. When they did get jobs, Black employees were paid less than white peers. And interracial marriage was illegal in many states. These restrictions left Black people with few, if any, options for escaping the confines of a racist system.

“You can’t work your way out of it, you can’t study your way out of it, you can’t marry your way out of it,” Qian says.

Which, for some, left the option of trying to pass.

Researchers have previously attempted to estimate the rate of passing, with wildly varying results. For instance, one 1947 study concluded that fewer than 2,600 Black people started passing as white per year from 1930 to 1940—about 0.2 percent of the Black population over that decade. A 1946 article in Collier’s claimed that other experts had put forth figures of roughly 15,000 to 30,000 people per year, which would add up to about 1.2 to 2.3 percent of Black people over that same time period.

Part of the problem was a lack of reliable data and of computing power. That changed in recent years: The U.S. government releases detailed records of individuals 72 years after the census is collected. In addition, computational power has increased, allowing researchers to perform intensive analyses such as searching millions of census records for matching profiles over time.

That’s exactly what Qian, Dahis, and Nix did. The researchers gathered records for men in the United States from six of the seven censuses from 1880 to 1940. (A fire destroyed the 1890 records.) In each of the first five censuses, the researchers randomly selected 10 percent of the Black men under age 55 to analyze, a total of about 2.1 million men over the entire study period. Tracking every Black man would have taken too long, even with the higher computational power available.

Next, they attempted to find these men’s records in the next census by searching all males of any race. Social Security numbers didn’t exist for most of the study period, so the team relied on other identifying details such as the name, approximate age (which people often rounded to a multiple of five), and birth place. To reduce the risk of incorrect links, the researchers threw out any matches that weren’t unique—for example, if one record in 1900 matched two records in 1910, it was discarded.

The algorithm didn’t catch cases where a Black man passed as white and also changed his name. But people wouldn’t necessarily have adopted a new name out of fear of being caught, Dahis says. The census data on individuals was kept confidential, and people who passed often moved to avoid detection.

Among the randomly selected 2.1 million Black men, the researchers were able to find a unique matching record in the next census for about 182,000 of them.

Of those men, about 30,000 of them had changed their race from Black to white. Extrapolated to the entire Black male population, that amounted to more than 300,000 men. In other words, an average of at least 1.4 percent of Black men under age 55 started passing as white per decade.

However, this estimate is very conservative, Qian says. The algorithm was not able to find unique matching records in the next census for about 1.9 million men, and the 1.4 percent passing rate assumes that none of those unmatched men passed—likely too extreme an assumption. Given that, the actual rate could be as high as 7–10 percent, the team says.

And another question remained: How could the team be confident that the men identified as passing had made an active choice to do so, and that the census-taker hadn’t simply written down the wrong race? To find out, the researchers conducted several tests.

“To live as a white person, a man moved away from his community and if his family was unable to pass for white with him, would cut himself off from his family. The psychological and emotional pain incurred was tremendous.”

— Nancy Qian

First, they performed a similar matching exercise for white men and looked for cases where their race changed to Black. The rate was very low, about 0.7 percent. The team also checked for instances of people’s race switching between Asian ethnicities—for example, Chinese to Japanese or vice versa. Again, the rates were negligible.

These results indicate that the much higher rate of men switching from Black to white reflects true cases of passing, not just census errors, Dahis says.

Next, the researchers examined the effects of passing on families.

When a Black man was initially married to a Black woman, and his race changed to white in the next census, he nearly always became single or had a white spouse. This suggested that the man had either separated from his first wife and, in some cases, gone on to marry a white woman—or that his wife had passed as white too.

And if these men had Black children, a similar trend emerged. In the next census, children in the same household were either absent from the census record or classified as white. Again, men who passed had either done so without their original family or gotten their entire family to pass.

Passing was also likely to involve moving to another county or state. Eighty-eight percent of Black men who passed did so, compared with only 39 percent of Black men who didn’t pass.

“It was personally costly,” Qian says. “To live as a white person, a man moved away from his community and if his family was unable to pass for white with him, would cut himself off from his family. The psychological and emotional pain incurred was tremendous. All of this suffering had to be done in secrecy and silence, which could have only added to the trauma.”

Lastly, the researchers looked at the effect on Black men’s income after they chose to pass. As one might expect, they earned more money.

The census did not indicate each person’s exact salary, but it did assign an income score. The average score was 16.4 points; after Black men passed, their scores rose by 3 points compared with Black men with similar demographic characteristics who didn’t pass.

In spite of the benefits, some men decided to return to their original identity after a while. About one-third of men who passed as white were recorded as Black in a later census. Biographers have shown that this was often to rejoin their Black communities or because they married someone who could not pass for white.

The study raises questions about economics research. “We usually think of someone’s identity as given,” Qian says. For example, if a researcher was studying trends in the labor market, they would control for race and assume that it stayed the same for a worker’s entire life. “But sociologists have long shown that identity, and in particular, race, is a social construction. Accepting this reality will help us to make better progress on addressing current issues about economic inequality and race”.

Dahis adds: “People always state race as an immutable, fixed category.” But racial identity “is surprisingly fluid.”

Roberta Kwok is a freelance science writer based in Kirkland, Washington.

Dahis, Ricardo, Emily Nix, and Nancy Qian. “Choosing Racial Identity in The United States, 1880-1940.” Working paper.