Featured Faculty

Previously a member of the Managerial Economics and Decision Sciences Department faculty

Michael Meier

Ameet Morjaria’s observations when he was a boarding-school student in Kenya helped motivate his recent study of the supply chain of the Kenyan flower industry.

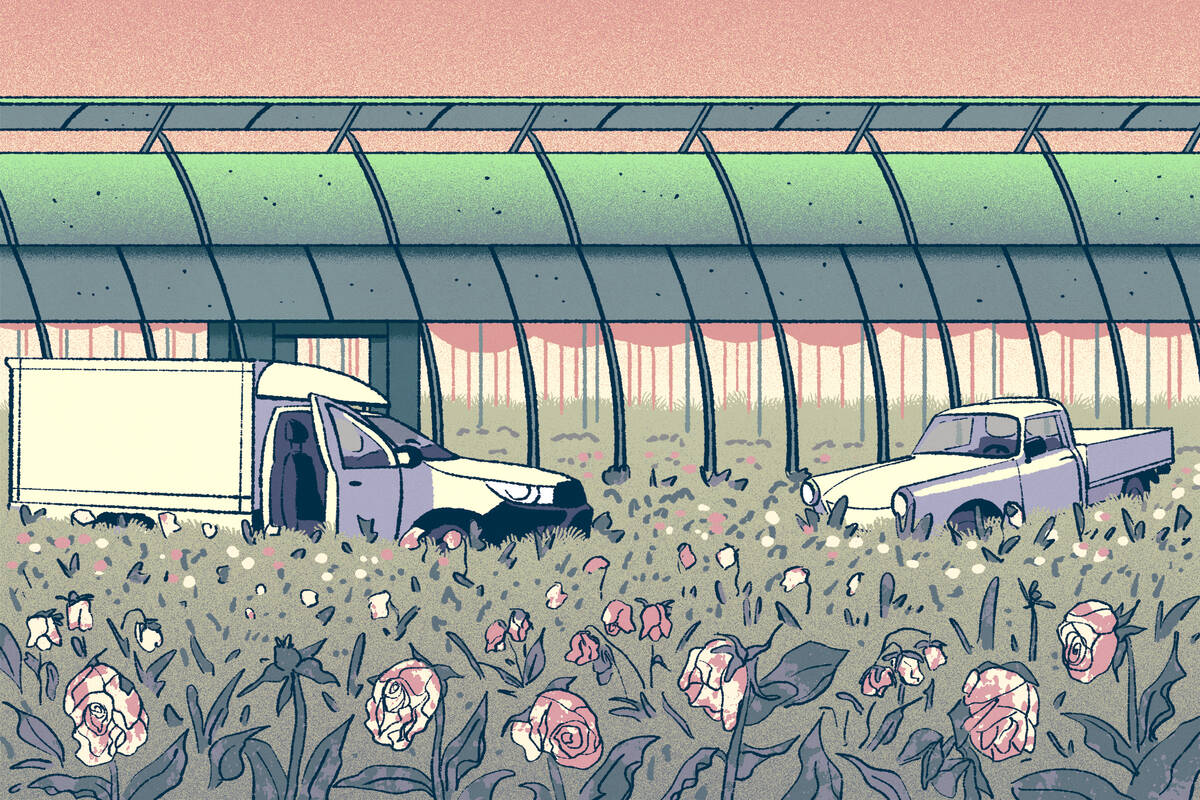

Flower farms link Kenya to global markets, explains Morjaria, an associate professor in the department of managerial economics and decision sciences at Kellogg. “Luxury products like flowers, which are transported at the constant temperature of one degree Celsius, travel within 48 hours from a farm in Kenya to a store shelf in London or Paris.” Yet these farms are still bound by events that happen on their doorstep, such as natural disasters, terrorism, or political violence.

As a way of understanding how such local events impacts the global supply chain, Morjaria set out to study how national-election-related violence affects the Kenyan flower industry, in terms of both supply and demand for that product. “In the last three decades, every fifth election in Sub-Saharan Africa is violent,” Morjaria says, “often bringing disruption and instability to large parts of the economy.”

To conduct their study, Morjaria and collaborators Christopher Ksoll of University of Greenwich and Rocco Macchiavello of London School of Economics focused on the aftermath of electoral violence in 2007. The violence impacted some parts of Kenya but not others, which allowed them to compare supply and demand patterns in areas where violence occurred with those in regions without violence.

The researchers found that electoral violence has negative impacts on both local producers and global buyers of flowers, with reduced exports caused by the disruption. These were the result largely of short-term labor shortages for the farms in areas affected by violence.

One big takeaway for all market participants is to plan proactively for possible supply-chain disruptions, whether related to election violence or other adverse macroeconomic phenomena.

“The goal is to plan ahead and have a structural hedge in place to not be caught off guard,” Morjaria says.

The Kenyan flower industry is among the world’s largest and has overtaken traditional producers such as Israel and Ecuador. The labor-intensive sector serves as a major employer of less-educated women in rural areas. At the time of the study, the industry included just over 100 established exporters.

Of note for research purposes, the flowers go almost exclusively to overseas buyers. Additionally, because the industry is regulated, there is comprehensive data available on export transactions.

The researchers examined the dynamics of the flower industry in early 2008, after ethnic violence following the general elections the previous December. Multiple outbursts of ethnically targeted violence took place until a power-sharing agreement was reached in February 2008. About 1,200 people were killed, and over 50,000 were displaced.

The researchers conducted face-to-face interviews with C-level managers at 75 flower-growing firms located in all producing regions, asking questions about whether the towns near their farms were affected by violence and how their businesses were impacted. The researchers then combined those data with the administrative export transaction data. This allowed them to compare changes in exports over time between firms in regions that experienced violence and in those that did not.

Electoral violence, the study found, has damaging effects on suppliers and buyers alike.

First, the volume of flowers produced in regions that witnessed violence was 56 percent below what would have been expected had the violence not occurred. Still, it wasn’t entirely clear why the supply was disrupted. As Morjaria notes, “The farms are in general outside urban areas where the friction between ethnic groups and violence was happening, so it was rare that a farm was directly destroyed.”

The study revealed that labor shortages were the cause of supply disruptions, as opposed to capital destruction, which is typical in more intense episodes of conflict.

“Workers were too scared to show up,” Morjaria says. Results suggested that 50 percent of workers were absent, on average, across farms in violent regions at the peak of the violence. This may have been in part because workers who lived in the nearby towns were wary of commuting during violent periods, they wanted to protect their families and belongings, or because workers were worried the urban violence could quickly spread to rural areas.

“Whether it’s political violence, trade wars, natural disasters, or conflict, these inevitably happen in an economy, and if you’re married to that economy, you rise and fall with its troubles.”

— Ameet Morjaria

But not every flower farm was affected the same way. Large suppliers were better able to weather the disruption, as were those with more direct, contracted relationships with global buyers that gave them incentive to keep up with demand for their flowers.

“If I’m a flower producer in Kenya and have these valuable direct relationships with the equivalent of Whole Foods or Trader Joe’s in Europe,” Morjaria says. “These are very difficult relationships to initially setup. So once I have a relationship, I will put in a tremendous amount of effort to maintain the relationship.”

These suppliers exerted extra effort to meet their obligations to the buyers. They were able to maintain typical product volumes, despite any labor issues, and they tended to have lower absence rates than farms without such direct relationships. This was often achieved by the producer providing housing onsite for workers, as well as organizing convoys of trucks with other producers and providing extra security for the convoys to get to the airport safely.

On the demand side, meanwhile, those purchasing flowers also faced disruption from electoral violence. Buyers had trouble quickly finding substitute suppliers outside of the regions experiencing violence, both within and outside Kenya, resulting in an estimated 17 percent reduction in flower deliveries.

“If I suffer from supply disruptions due to political volatility in Kenya, I start to seek sourcing from outside Kenya,” Morjaria says. “I might try to shift my strategy to procure from Ethiopia, but as I mentioned earlier those relationships are hard to get into and certainly not possible overnight. There’s a lot of due diligence on both sides.”

So in the end, global flower buyers are left with few alternative sourcing options in the short term.

While Morjaria’s work shows that both supply and demand suffer because of electoral violence, there’s also evidence that producers have learned from past disruptions.

“Five years after our initial research, in the lead-up to the election in 2013, we reached out again to the flower farmers and asked if they were worried about potential political risk in light of the upcoming election,” Morjaria says. “They said, ‘No, no, Kenya has come a long way since those events.’” Even so, there was some cautiousness in their transaction data. “Export volumes jump up a little prior to the election. We read this as extra effort to clear inventory in case there are disruptions.”

Morjaria sees two broad takeaways from the research that pertain to any global markets facing supply-chain disruptions, including those related to the COVID-19 pandemic, natural disasters, and the current war in Ukraine.

First, there are social benefits to the contracted relationships that flower producers were able to establish with buyers. “When these contractual arrangements are in place, producers will prioritize them and make extra effort to maintain them,” he says. The research provides a novel rationale for why policymakers in countries prone to political instability might promote the adoption of such arrangements among exporters.

Second, for global buyers the lesson is about diversification in order to avoid overreliance on one particular supply source or region. “Whether it’s political violence, trade wars, natural disasters, or conflict,” Morjaria says, “these inevitably happen in an economy, and if you’re married to that economy, you rise and fall with its troubles. So, diversify your supply chain. But that’s easier for those with deep pockets and capabilities to manage that structural risk.”

Indeed, the world is seeing the critical importance of diversified supply chains right now, due to challenges like the recent trucker pandemic protests at the U.S.-Canada border and the motivation to seek oil-and-gas products from markets other than Russia, due to the war in Ukraine.

In short, for both supply- and demand-side players, a proactive, rather than reactive approach is optimal. “The macroeconomic adversities we’re talking about are no longer if events; they are more like when events,” Morjaria says. “You have to be ready for that when probability to change quickly, so ask yourself, ‘Do I have structures in place to withstand these adversities?’”

Sachin Waikar is a freelance writer based in Evanston, Illinois.

Ksoll, Christopher, Rocco Macchiavello, and Ameet Morjaria. Forthcoming. “Electoral Violence and Supply Chain Disruptions in Kenya's Floriculture Industry.” Review of Economics and Statistics.