Policy Dec 9, 2025

Should I Feel Guilty about Using AI?

While AI queries have a modest carbon footprint, power-hungry data centers need more transparency and regulation.

Because Matthew Roling is an environmentalist, he often gets a surprised response when he says he uses AI tools.

“I’ve met a lot of people who say, ‘oh my gosh, you use AI? But you’re the climate person! Don’t you know that AI queries have a high carbon footprint?’” says Roling, a clinical assistant professor at Kellogg and the executive director of the Abrams Climate Academy. “It got me thinking, ‘Am I underestimating the climate impacts of these new tools?’”

The self-reflection led Roling to dig into how the carbon emissions related to using AI applications compare with those of other daily activities, from streaming a movie to eating meat. What he found was a familiar pattern in climate and sustainability debates, where individual behaviors are misunderstood compared with the environmental impact of corporate decisions.

As tech companies race to build the infrastructure powering the AI era, the real question lies not in how individuals use chatbots, but in the policy decisions of state and local regulators. By setting standards for energy efficiency, water use, and sustainable siting of hyperscale data centers, regulators can ensure these massive projects deliver better outcomes for communities and the environment.

The focus, Roling says, should be on guiding hyperscalers toward responsible resource consumption, rather than worrying about the marginal impact of someone asking for a recipe online.

“It’s not that AI has no environmental impact. But if that’s your concern, AI isn’t the straw that breaks the camel’s back as it relates to an individual’s carbon footprint,” Roling says. “Yet AI still is creating tremendous strain on energy systems in the United States. And we’re seeing demand for electricity in a way that we haven’t in decades.”

Roling describes the energy impact AI usage is having, from individuals to companies to data centers, and what actions can make a big difference in the technology’s carbon footprint.

Putting AI use into context

The average American generates around 20 tons a year of carbon dioxide, mostly through transportation and home energy use. A cross-country U.S. flight may emit more than a quarter ton of CO2 per passenger; a 20-mile roundtrip commute in a gas-consuming car can contribute as much as five tons of carbon per year.

By comparison, what you do on your computer generally leaves a much smaller carbon imprint. A standard AI query—when you ask ChatGPT a question, or when Google provides you with an AI overview—generates about five grams of carbon dioxide. That’s ten times higher than a normal Google search—but about 300 times less than streaming an hour of video.

Roling’s favorite comparison point is the hamburger, which generates between 2 and 3 kilograms of carbon from farm to table—the equivalent of hundreds of AI queries. While generating images or video requires more energy, these are less-routine tasks.

“So, for the individual who is using AI sporadically throughout the course of a week to help them with work or their personal life, it doesn’t even compare to some of the other things that we do that aren’t judged as being environmentally imprudent,” Roling says. “All I have to do is eat two fewer hamburgers a year and I’m fine.”

Data center energy use

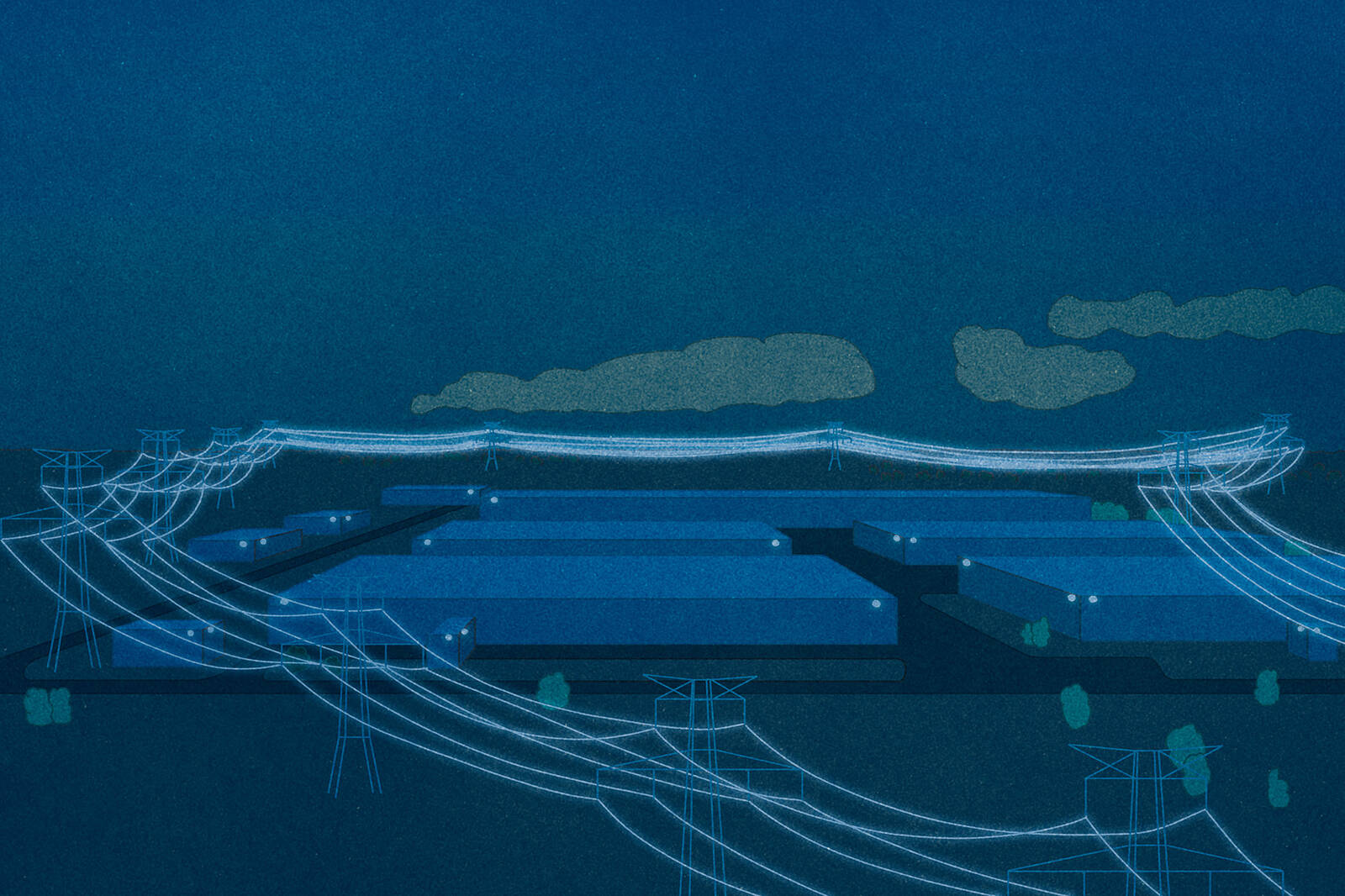

On the other hand, the infrastructure necessary to perform those individual AI tasks may have much larger consequences. As companies race to build out “hyperscale” data centers to power tomorrow’s AI applications, the massive, energy-hungry construction projects are creating new environmental stresses.

After 15 years of relatively flat growth in energy demand, the U.S. set an all-time high of electricity consumption in 2024—and it is expected to grow rapidly in coming years. Currently, 4.4 percent of all U.S. energy goes to data centers, and that’s projected to triple by 2028, reaching between 165 and 326 terawatt-hours per year. That’s enough to power nearly a quarter of American homes.

“For the individual who is using AI sporadically throughout the course of a week to help them with work or their personal life, it doesn’t even compare to some of the other things that we do that aren’t judged as being environmentally imprudent.”

—

Matthew Roling

While other trends, such as electric cars and reshoring manufacturing, are contributing to this demand surge in the U.S., the big driver is AI and the Big Tech companies behind it, Roling says. That puts these previously “green” leaders in an unfamiliar position.

“The hyperscalers—Microsoft, Google, Meta, Amazon, etc.— are companies that have historically been at the forefront of setting emission-reduction targets,” Roling says. “And now you see many of them walking these goals back—or being a little bit more cautious about them—because they’re in the midst of this arms race and they need to build as many of these data centers as fast as possible.”

Transparency around resource use

With demand growth outpacing grid bottlenecks, and policy or permitting delays slowing renewable-energy construction, hyperscalers have needed to rely on existing fossil-fuel infrastructure to provide the 24-hour reliable energy their data centers require. As a result, many of these companies are suddenly investing in natural gas and even coal power plants as a short-term solution. Others are eying nuclear power, though the regulatory and technological hurdles remain high.

“At the margin, you see these companies trying to do innovative things to showcase their green bonafides,” Roling says. “But because it’s such a race, they’re going to take electricity wherever they can get it, as cheaply as they can. And that often is in communities where it’s coal or natural gas, which is very carbon intensive and very bad for air pollution and for human health.”

Another concern is water, which is used by data centers to cool the heat generated by hundreds of thousands of computer chips. Some estimates say that hyperscale data centers need five million gallons of water a day—an amount that is especially concerning given the amount of construction planned in regions that are already water-stressed, such as Texas and the Southwest.

One caveat to these figures is that most of them are estimates, because, in the hyper-competitive AI boom, companies are rarely sharing information about their resource needs and impacts with regulators or communities. As local resistance to planned data centers intensifies, Roling hopes to see more information released by technology companies about their energy and water consumption and how they plan to account for it.

“Disclosure and transparency are paramount, especially because of how fast this freight train is moving,” Roling says. “I am sympathetic to the need to protect trade secrets, but at the same time, clean air, clean water, and our atmosphere are common goods that need to be protected.”

The impact of companies

In considering the environmental impact of AI, it is also important to recognize that the customer base for many tools isn’t individuals—it’s companies. As more organizations incorporate AI into their operations, they will pay large fees to suppliers of the technology.

That may give those firms some influence in keeping the energy demands of data centers in check, Roling says. There’s historical precedent in the rise of cloud computing, where companies across industries suddenly found themselves purchasing remote server space. In that era, Roling worked with a video-game producer who was thoughtful about choosing their cloud vendor based on the carbon intensity of their server farms.

“If you are putting a lot of money out the door that’s going towards data centers, as a corporate leader, you have the opportunity to engage with that vendor and, if appropriate, move your spending to the lowest carbon provider,” Roling says.

And as electricity bills rise for companies and households alike, Roling also sees a potential silver lining as utilities and tech companies have new price incentives to innovate and incorporate cheap renewables.

“I’m hopeful that, to address the demand challenges caused by AI, we are going to start to see states and utility companies look at options that are more modular, that are more incremental, like wind, solar, and storage,” Roling says. “There are a lot of technologies that I think we’ll see emerge as we grapple with this problem. Because if there’s one lesson we’ve learned in the last five years, it’s that inflation is very unpopular. We didn’t feel it in energy the last five years, but we’re starting to feel it now.”

Rob Mitchum is editor-in-chief of Kellogg Insight.