Featured Faculty

Harold T. Martin Professor of Marketing; Director of the Center for Market Leadership

runeer via iStock

When Intel’s CEO announced that “every idea and technical solution should be focused on meeting customers’ needs from the outset,” he was proposing a radical shift from an organization focused on microprocessor design to a company whose culture would prioritize understanding and meeting specific customer needs (Edwards, 2005). As more firms make the effort to become customer-focused, it is important to comprehend not only what a market orientation is, but also how such a transformation occurs.

A market orientation describes the process by which a company determines current and future customer needs and disseminates this information throughout the firm’s various divisions, which then act together as a unified organization to meet specified customer needs (Kohli and Jaworski, 1990). To companies with a market orientation, a focus on the customer is paramount. Merely defining a market orientation, however, is easier than actually creating a more customer-focused organizational culture. Some managers know what things in their organization need to be changed but do not know how to effect that change.

To promote a culture of “Harleyness,” Harley-Davidson evaluates prospective employees on their level of cultural fit and encourages employees to own and use motorcycles.How does a firm implement the cultural changes that will make customers a top priority in its organization? To answer this question, Gary Gebhardt (University of South Florida) joined forces with Gregory Carpenter of Kellogg’s marketing department and John Sherry (University of Notre Dame) to get an up-close look at companies in different stages of organizational change.

Four Stages to Creating a Market Orientation

Employing a variety of qualitative research methods such as oral histories, ethnographies, and historical documents, the researchers examined seven firms that were just beginning to adopt a greater market orientation, already in the process of such a change, or had recently completed the transformation. Over a period of ten months, the researchers conducted formal interviews with seventy employees; spent more than forty days observing and speaking with employees in executive meetings, during meals, and in company work and break areas; and reviewed hundreds of historical documents such as annual reports, press releases, and industry publications.

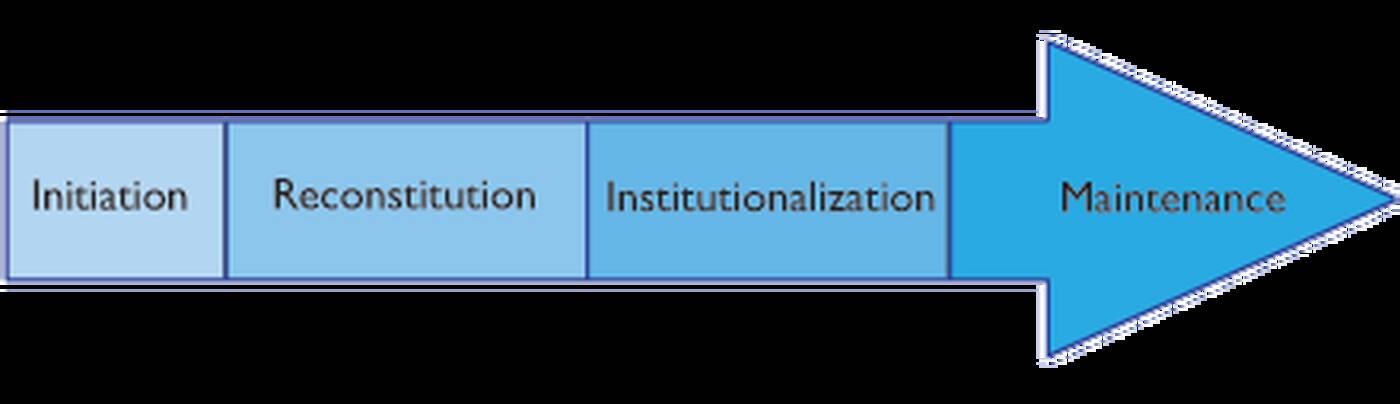

As Figure 1 illustrates, the analysis identified four stages in the process of creating a market orientation: (1) initiation; (2) reconstitution; (3) institutionalization; and (4) maintenance.

During initiation, executives or other powerful stakeholders first recognize an external threat to the company (such as failure to meet financial performance targets) and then prepare to implement a market orientation by identifying specific initiatives for the transformation process. For example, one of the companies studied was losing millions of dollars in revenue. In response, senior management outlined a new set of values expected of organization members (e.g., empathy, respect for others, collaboration) and identified process-focused change initiatives (e.g., communication systems, continuous improvement, information technology).

The next stage, reconstitution, involves presenting the plan to the entire organization simultaneously. The plan should describe the values that have been selected to guide the firm’s behavior, as well as the specific change initiatives that will occur. After presenting the plan, the firm can promote an organization-wide understanding of how cultural values affect the company’s ability to meet market needs by sending cross-functional teams to meet with customers and other key stakeholders. Ultimately, personnel who are unwilling to support the cultural transformation are replaced by new hires who share the values important to the organization. Once all the employees of a firm agree on a definition of the market and its unmet needs, they can collaboratively develop a strategy to meet those needs.

Together, these factors enable market-oriented firms to monitor and react to changes in the marketplace.

The third stage, institutionalization, occurs as a market-oriented culture becomes formally incorporated throughout the organization. Employee rewards are aligned with the firm’s performance in the marketplace; training is designed to reinforce cultural values; and decision-making power is decentralized and extended to all members of the organization. For example, during a transformation-related meeting between the shipping and sales departments, one company used suggestions from employees in both departments to resolve a communication problem; the result was a pricing structure adjusted to reflect actual shipping costs while still providing customers with the shipping options they wanted. Some executives in the companies that were studied relinquished their decision-making power and instead provided others with the values and information that should guide their decisions.

Finally, during the maintenance stage, the company protects its market-oriented culture from deterioration by screening new hires to ensure they fit the restructured image; creating activities that remind employees of the process of cultural change the company has undergone; and staying connected to the market through research and field visits. For example, to promote a culture of “Harleyness,” Harley-Davidson evaluates prospective employees on their level of cultural fit and encourages employees to own and use motorcycles; its executives attend rallies to keep in touch with customers. Maintenance requires firms to accept new policies and strategies only when they are consistent with core values.

More than Mere Lip-Service

These four stages show that the process of creating a market orientation involves more than simply performing a set of behaviors; it requires the widespread adoption of an organizational culture based on common values and a shared understanding of the market, as well as the distribution of intra-organizational power. Although the change process generally is initiated by an elite group, interdepartmental cooperation and proper reward systems are also critical to the successful implementation of a market orientation. Together, these factors enable market-oriented firms to monitor and react to changes in the marketplace.

Although firms may “talk the talk” of a market orientation, companies can “walk the walk” by successfully implementing cultural change designed to focus organizational efforts on meeting customer needs.

References

Edwards, Cliff (2005). “Shaking up Intel’s Insides.”Business Week, 3918: 35-35.

Kohli, Ajay K. and Bernard J. Jaworski (1990). “Market Orientation: The Construct, Research Propositions, and Managerial Implications.” Journal of Marketing, 54(2): 1-18.

Gebhardt, Gary F., Gregory S. Carpenter, and John F. Sherry (2006). “Creating a Market Orientation: A Longitudinal, Multifirm, Grounded Analysis of Cultural Transformation.” Journal of Marketing, 70(4): 37-55.