Policy Apr 1, 2024

AI Has Entered the Court. Is This Changing Umpires’ Calls?

The Hawk-Eye review system in professional tennis has made umpires more accurate in many cases—but not all.

Michael Meier

Umpires can make or break a sporting event. Just ask Serena Williams.

In 2004, when the tennis star faced Jennifer Capriati at the U.S. Open, a series of controversial calls plagued her in the final set. Williams lost the match and afterward complained that an official’s calls robbed her of a win. Many people agreed.

That bit of umpiring served to usher in the use of Hawk-Eye, an artificial intelligence program that gives technology the final word on whether a ball is in or out of bounds in professional tennis. With AI watching the court, players can challenge an umpire’s call when they believe it is inaccurate. If the system contradicts the original call, the umpire’s decision is overturned.

So how did umpires’ behavior change when they knew Hawk-Eye could overrule them—and what might this tell us about human decision-making in the age of AI?

New research by Kellogg’s Daniel Martin, an associate professor in managerial economics and decision sciences, and David Almog, a PhD student in managerial economics and strategy, takes up these open questions. The study was coauthored by Romain Gauriot of Deakin University and Lionel Page of the University of Queensland.

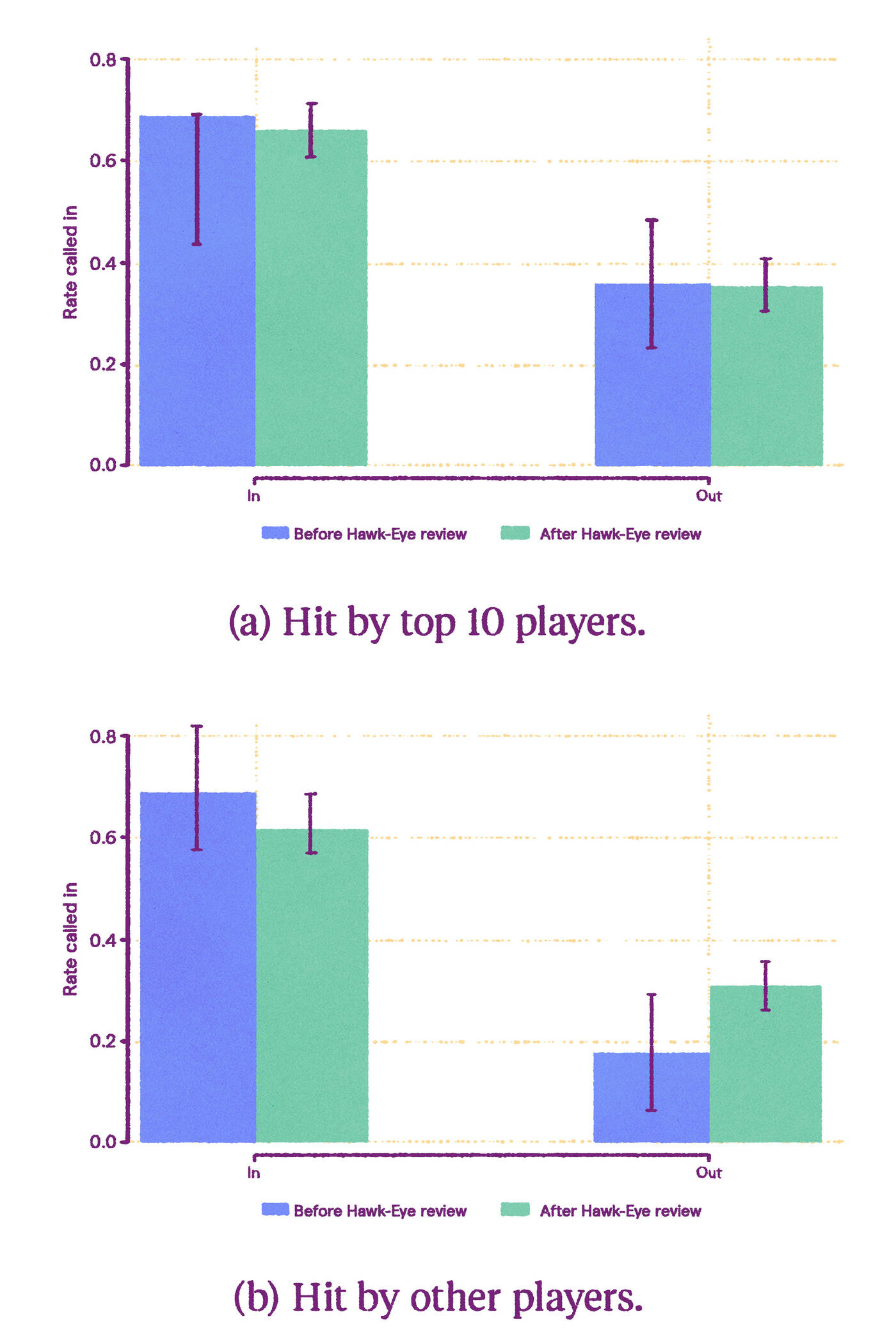

Using a robust set of Hawk-Eye data, the research team analyzed the technology’s effect on how umpires called matches. What they found: in general, umpires’ accuracy improved when they knew that AI could contradict them; their overall mistake rate dropped by 8 percent after the introduction of Hawk-Eye.

Curiously, however, there were certain situations in which umpires’ mistake rate went up after AI came on the scene. Close serves were the most noticeable: the mistake rate for those rose by 22.9 percent. And the sudden rash of errors, the researchers found, stemmed from a newfound tendency for umpires to call balls in that were actually out. This suggests that, consciously or not, umpires were reacting to new psychological pressures on the court.

Of course, it’s not only tennis umpires whose jobs have been disrupted by AI. Today, many high-stakes fields, including finance and air traffic control, have begun implementing AI oversight systems.

“People are not going to make the same choices if they think that their decisions might be overruled by AI.”

—

Daniel Martin

For that reason, the researchers say, it’s not enough to understand how AI works—we also have to understand how humans behave when the technology is watching. And while it can improve the ways people do their jobs—especially when making difficult or quick decisions—there can also be downsides.

“This paper sits at the intersection of two things. One is: AI is incredibly exciting as a technology to improve our lives,” Martin said. The other: “The unintended consequences of adding AI into our world, into our workplace. And part of that is people are not going to make the same choices if they think that their decisions might be overruled by AI.”

Keeping an eye on the ball

Hawk-Eye uses six to ten computer-linked cameras around the court to create a 3D representation of the ball with respect to the service lines, performing with an average error of 3.6 millimeters. Meanwhile, a crew of up to ten human umpires, including a chair umpire overseeing it all, officiates the match. Tournament players are allowed two to three challenges per set, in which Hawk-Eye is used to check the work of the human umpires.

Martin and Almog’s study drew from two datasets and covered 698 matches—109 from the system’s testing period and 589 from after 2006, when Hawk-Eye was officially introduced in competition.

Overall, umpires improved their accuracy after the introduction of Hawk-Eye, lowering their mistake rate by 8 percent, researchers found. But for close calls, especially serves, a different story emerged.

Most notable was a shift in the type of mistakes made. On the closest calls—those within 20 millimeters of the line—the rate at which umpires called balls in rose by 12.6 percent after Hawk-Eye was introduced. Umpires went from making what the researchers call Type II errors (calling the ball out when it was in) to Type I errors (calling the ball in when it was out).

The researchers believe this shift stems from a desire to avoid a particularly thorny situation: if an umpire stops a point by calling a ball out when Hawk-Eye shows it was actually in, there’s no easy way to fix the error. After all, you can’t put the ball back into motion and resume play where it left off. Instead, the umpire has to decide whether to replay the point or award it to the challenger. It doesn’t help that the umpires learn of their mistakes in a very public way: the AI analysis of the ball and the court line are projected on a large screen, with players and fans reacting—stirring up feelings of shame, pride, or embarrassment.

Even with this added concern, the rate of errors on non-serve close calls decreased modestly after Hawk-Eye was introduced—perhaps, the researchers suggest, because the presence of AI nudged umpires to pay closer attention. And because non-serves are slower-moving and ball placement is therefore easier to spot, their extra vigilance resulted in greater accuracy.

Meanwhile, for close calls on serves (which move much faster but are focused on a specific quadrant of the court), the mistake rate increased by 22.9 percent with the introduction of Hawk-Eye. Umpires were already paying very close attention to the lines during serves, and it’s possible that even under AI’s watch, they weren’t able to improve on their accuracy. However, the added pressure that Hawk-Eye brought to their job—and perhaps the umpires’ concerns they’d make that difficult Type II error—made them change their behavior when the calls were very close.

“Once you see the data, you’re like, wow, these are really different attentional problems for referees,” Martin adds. One task (judging serves) is more focused, since the judge knows approximately when and where the ball will go. The other (judging lines over the rest of the court) is more general. AI shifted decision-making in one case and impacted attention in the other, Martin says.

Hawk-Eye undoubtedly improves the officiating of a tennis match, even as the umpires’ behavior changes, Martin says. “The combination of humans plus AI in terms of tennis umpiring is way better than what existed before,” he says. “What we study in that paper is: How does it change how good umpires are—not how good final decisions are? Final decisions are way better.” In other words, AI assistance in officiating tennis matches makes the game fairer overall, even if it does cause some behavioral shifts in umpires.

Beyond the tennis court

All of which is to say that AI oversight, while providing some real benefits, has the potential to create changes in how any worker behaves. AI could reduce inequality, for example, if it is used to alert managers to biases in their decision-making. That’s a positive check that can create fairer workplaces. That said, just knowing that AI is monitoring us and waiting for us to slip up can be creepy—and can distort our behavior in unanticipated ways.

Imagine, for example, a pretrial bail judge decides to allow a defendant to go free—only to be overturned by an algorithm that determines the person is too dangerous to be let out of jail. The threat of being overruled might shift the judge’s decisions, says Almog, “so they might be biased to release fewer people.”

As research piles up, scholars can help inform decisions over the best use of AI, Martin says. “Do I want to replace the human? Do I want to just replace them in situations of egregious mistakes or egregious bias? As policymakers or as firms, you kind of have a meta choice about when to employ AI oversight, or AI monitoring,” he adds. Back in the sports world, there’s already discussion about replacing humans in baseball, where a computer would assess balls and strikes behind the plate.

One thing is certain: As we venture into the new reality of AI oversight, policymakers and firms will have little to go on as they try to parse the consequences of introducing this technology before it is adopted on a large scale. This will make studies like this one important. “This literature is going to have an outsized impact on regulation, because it’s just a tiny light in the dark,” Martin says.

Amy Hoak is a freelance writer in Chicago.

Almog, David, Romain Gauriot, Lionel Page, and Daniel Martin. 2024. “AI Oversight and Human Mistakes: Evidence from Centre Court.” Working paper.