Featured Faculty

IBM Professor of Operations Management and Information Systems; Professor of Operations

Yevgenia Nayberg

Efforts to make companies more environmentally friendly have never been more popular.

The number of LEED-certified commercial and institutional buildings—designed to use less water and energy than typical structures—for instance, has increased from fewer than 50 in 2000 to more than 21,000 in 2014. And the share of companies included in the S&P 500 Index that issued “corporate sustainability reports” jumped from just 20 percent in 2011 to 75 percent in 2014.

Such initiatives may be good for the environment, but what effect do they have on the companies that pursue them?

Most research has analyzed the impact of these “eco-activities” on share prices, and the results have been mixed. Some studies show that eco-friendly practices have a negative effect on a company’s stock price; others show a positive effect. In either case, the impact registers almost immediately after a company announces the activity.

Sunil Chopra, a professor of operations management at the Kellogg School, approached the question from a different perspective. Rather than focusing on stock prices, he analyzed companies’ operating performance—a range of measures that include costs, revenues, margins, and profits. This method yields a more robust and longer-term picture of the impact of eco-activities.

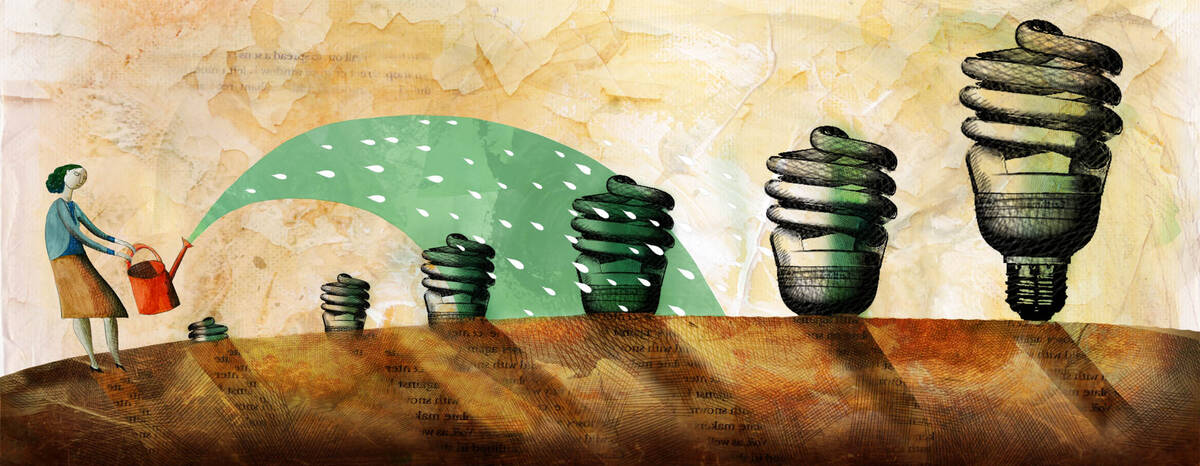

Chopra found that going green is like many investments: the more resources you put in up front, the greater the potential payoff. But to realize the rewards, “you have to show sustained commitment,” Chopra says. “You can’t give up too soon.”

Chopra and his coauthor, Pei-Ju Wu of Feng Chia University in Taiwan, used a database of press releases to identify companies in the computer and electronics industry that announced an eco-activity between 2000 and 2011, and that had publically available financial data.

“Collaborations often involve other parts of the supply chain. They’re more complex, and they require an initial investment. But they do seem to pay off.”

They paired each company with a control firm that did not initiate eco-friendly practices but was similar across a variety of factors, including its geographical location, size, sales, and assets. “Our goal was to find the linkage between eco-activities and changes in operating performance,” Chopra says. “So we tried to find firms that were very similar to those that engaged in environmental actions—except that they didn’t.” This rigorous filtering process left the authors with 71 pairs of companies to analyze.

When the researchers analyzed the operating performance of companies for two years prior to the announcement and two years following it, they found that overall eco-activities paid off: companies that pursued them performed better than those that did not, and the difference was especially striking in the second year following the announcement.

Researchers also found that the approach to sustainability that each company took had a sizeable impact on the timing and size of the economic benefits they experienced.

Companies that engaged in eco-activities generally fell into one of two buckets: those that engaged in activities that could be performed independently and those that engaged in activities that required collaboration with other companies. The first bucket includes activities like increasing the fraction of packaging material recycled, while the second bucket includes examples like Hewlett-Packard’s 2007 adoption of a new technology created by Citrix Systems, designed to lower the consumption of power and cooling resources in computer servers. Among companies that engaged in eco-activities, a subset also followed the directives of, and received certification from, a standard-setting organization like the U.S. Green Building Council, which offers the popular LEED certification.

The companies that acted independently reaped immediate benefits. They outperformed those that did not pursue environmental initiatives, as well as those that pursued them in collaboration with other companies, in the year before they announced an eco-activity. (Since a press release sometimes follows the initiation of eco-activities, the activities can begin to impact a company’s operating performance before they are actually announced.)

By the second year after the announcement, though, their operating performance was about the same as that of the control companies.

By contrast, companies that collaborated on eco-activities underperformed both the control group and the independent actors in the year before the announcement. In the two years following it, though, their performance improved substantially, surpassing both the control group and the companies that pursued eco-activities independently.

Chopra notes that collaborative efforts are often more costly to set up than activities that can be pursued independently.

“If you’re just doing something like changing the light bulbs, that’s simple and has an immediate benefit,” he says. “But collaborations often involve other parts of the supply chain. They’re more complex, and they require an initial investment. But they do seem to pay off.”

And certified eco-activities had an even more powerful impact on operating performance. Companies that obtained a certification had substantially better operating income, gross profit, and revenue than the control companies they were compared against—more than compensating for the the higher costs they faced. Overall, these companies fared best of all relative to their controls who undertook no environmental initiatives.

Eco-friendly practices are often framed as money-saving measures: consider the way energy efficient light bulbs are marketed, with the “annual cost savings” printed right on the packaging. But Chopra found that operating performance improved even though companies realized few, if any, cost savings from their eco-activities.

So where did the benefit come from then?

One theory is that complex eco-activities—the kind that involve collaboration and certification—often impose steep up-front costs, but over the long run can become a competitive advantage and generate more business.

“Certification sets you apart,” says Chopra. “This can go down to the consumer level. If I’m going to buy coffee, I might buy coffee that’s certified by a certain alliance. But certainly, at the business-to-business level, certifications help in that regard. If not everybody is able to get certified, you become part of the subset of suppliers or manufacturers that are certified. So you’re likely to be able to grow your market and grow your revenues.”

That reality underscores the truth that eco-friendly practices should be approached as a long-term investment. They’re good for the environment, and the evidence suggests that they’re good for the bottom line—but perhaps not right away. Patience is required.

“You might not see the benefits for a while,” Chopra says, “so it’s important for top management to have a strong commitment to them.”