Yevgenia Nayberg

Michal Maimaran was out walking in Evanston when she bumped into her family’s pediatrician and struck up a friendly conversation—a chance encounter that inspired a new research project.

Maimaran, a research associate professor of marketing at the Kellogg School, has been studying decision-making in children for several years. So her ears perked up when the doctor mentioned he had observed parents giving children lots of options about various day-to-day activities: At the park, would she rather play on the slide, or the swings, or kick a ball around, or throw a Frisbee, or climb a tree? At home, which of the dozens of books on her shelves does she want to read?

The doctor was troubled by this approach. And Maimaran knew research has shown that having an abundance of choices can be a bad thing—at least for adults.

Psychologists and marketers have previously found evidence that having lots of choices can feel overwhelming or make us regretful of our final choice—a phenomenon known as “choice overload.” But no one had really looked at how an abundance of choice affects children, and in particular, how having so many affects how engaged they are with the option they ultimately choose.

Maimaran started to reflect on the choices she offered her own children, and critically, how much they actually engaged with their final selection. After all, she says, “what matters most is, after you chose something, what do you do with it?”

Thus, a research project was born.

She found that there can be negative consequences to giving children lots of options to choose from. In several studies she showed that when kids pick from a large set of options, they spend less time engaged with their choice than when they pick from a small set.

Over time, Maimaran suggests, using choice sets strategically can have an effect on the kinds of activities that children find interesting and enjoy, something parents, educators, and policymakers may want to keep in mind.

“What matters most is, after you chose something, what do you do with it?”

For example, if you want to keep your child’s nose in a book, you may be better off giving them just two to three titles to choose from, rather than a hefty stack. The same idea holds for other beneficial activities, such as educational games and playing outside. On the flipside, though not studied directly by Maimaran, you might be able to shorten the amount of time kids spend on less desirable activities, such as video games, not by cajoling them, but simply by offering them a larger selection of games to choose from.

Curious George and the Study of Decision-Making

Maimaran got some help in her research from a beloved monkey and a man with a yellow hat.

Curious George’s creators probably didn’t plan on it, but they wrote the perfect series for a study of children’s decision-making: the books included in the study are the same length, 24 pages each, and share a similar cover design scheme. As an added bonus, the series is widely popular among both boys and girls, eliminating concerns about gender as a confounding factor.

In one of the studies, preschoolers were asked to select a book from a set of either two or seven Curious George titles. Afterward, the kids, who were not reading yet, were invited to look at the book for as long they liked.

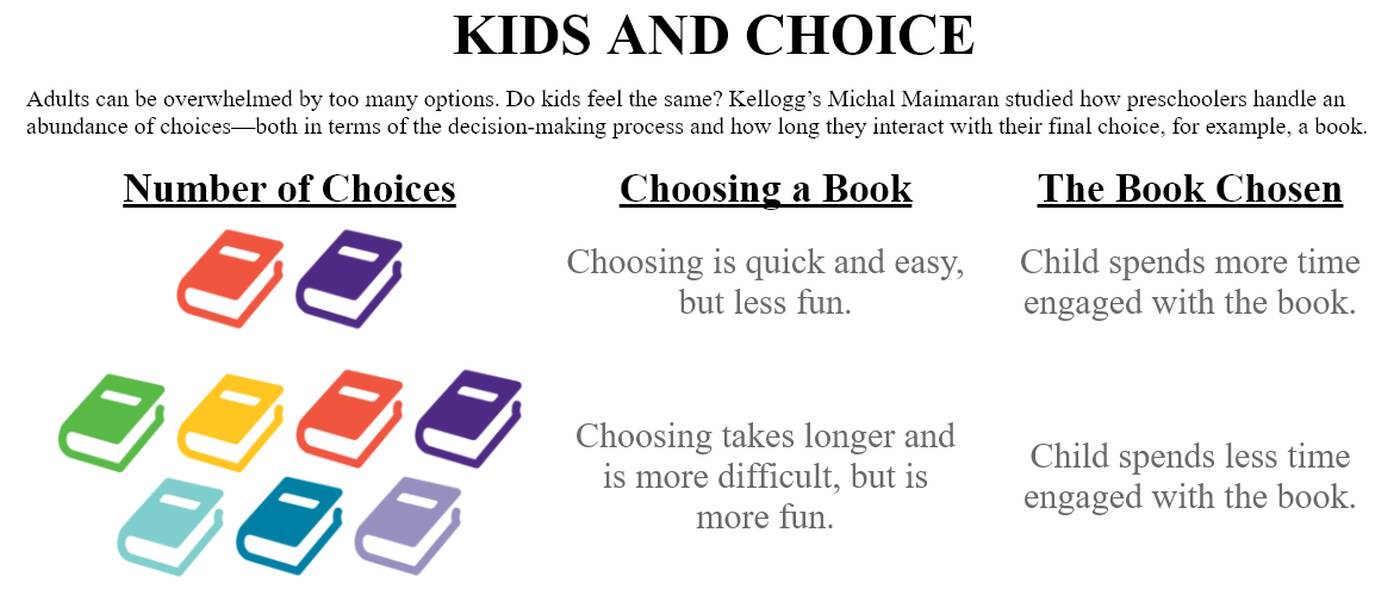

Maimaran finds that children who picked between two Curious George books spent less time arriving at their choice and more time looking at the book compared with children who chose from among seven options.

When she repeated the test with a different group of children using sets of differently colored building blocks, rather than books, Maimaran observed the same result: children who picked from a set of two spent twice the time playing with the blocks compared with children who picked from among six options.

So why is this happening?

Maimaran says more research is needed to understand the precise mechanism underlying the effect of choice size on engagement in children. But she suspects that when children’s cognitive resources are spent on the act of choosing something, there is less attention and energy left to enjoy the thing itself. At the same time, she suggests, choosing from the large set can be an engaging task in and of itself, especially for children, leaving the children with a less of a need to engage with the option they ended up choosing.

When Making Choices Is Difficult, Yet Fun

Beyond engagement with their final choice, Maimaran also wondered how the kids felt about the actual act of choosing.

So another study asked the preschools if they thought choosing from a small set would be easier or harder than choosing from a large set, as well as which they thought would be more fun to choose from. The consensus was that the small set would make choosing easier, but choosing from a large set would be more fun.

And, by a wide margin, they stated they would prefer to pick from a large set.

It’s a puzzling preference. Why would kids opt to do something they find harder?

“It could be that the desire to have fun and enjoy overrides avoidance of difficult tasks,” Maimaran proposes.

Or perhaps kids are simply rational actors. After all, she says, the more options you have, the more likely you are to find one that suits your needs, even if it is a more difficult process.

But, it seems, being able to find the most suitable choice still does not guarantee you will use it more.

Why More Isn’t Always Better

Maimaran’s research finds that offering children too many choices makes them less likely to engage with their final selection. Do adults respond in the same way.

Previous evidence suggests that “choice overload” in adults can lead to less satisfaction with a final choice, or the inability to make a choice at all. But because very little research has explicitly studied how much adults use their final selection, it is hard for Maimaran to predict whether the behavior she observed in preschoolers would hold true throughout the lifespan. After all, adults, more so than young children, may feel the need to justify their lengthy decision-making process by engaging more with their choice.

When it comes to her own children, Maimaran is practicing what her research suggests.

If her kids are making a purchase, she’ll identify a small subset of options and let them choose from among those. “This is easier done online than in the store,” she says, “where you’re just overwhelmed, standing in front of this aisle with so many options.”