Innovation Marketing Aug 1, 2016

Companies Brag about Being Innovative. Should They?

Certain circumstances make customers wary of innovative brands.

Michael Meier

The next time Apple releases a much-ballyhooed new product, don’t look for Kelly Goldsmith waiting in line to buy it.

Not that Goldsmith, an assistant professor of marketing at the Kellogg School, has anything against the company. It is just that her research has made her sensitive to the potential downside of innovation.

“Everyone likes a fancy new phone with new features,” she says. Yet, “as much as there are upsides to innovation, there are always downsides.”

In new research, Goldsmith and coauthors Jeffrey S. Larson of Brigham Young University and B.J. Allen of the University of Texas at San Antonio examine the ways in which a reputation for innovation can actually hurt a company.

Specifically, trumpeting an innovative brand can backfire when something about the product triggers a customer’s concern, or because the customer is in a fretful state of mind.

“We weren’t predicting that a reputation for innovation is always going to have negative consequences,” Goldsmith stresses. If that were the case, no company would tout its innovativeness, and publications like Forbes and Fast Company would not create lists of the most innovative brands.

“It’s only going to have negative consequences when consumers are prompted to worry,” she says. “Most people, most of the time, expect their products to work. We’re lucky enough to live in a day and age where product malfunctions certainly aren’t that common—and that’s why they stand out so much when they do happen.”

When Worry Kicks In Over Innovative Brands

The researchers started by priming participants to worry about a product malfunction to see if that did, indeed, sour them to innovative brands.

In one study, 266 participants recruited online were randomly assigned to write about either a few times a product malfunctioned or about a few things they did in the past week.

Each participant then read print advertisements for a hypothetical digital-camera company. Some of the participants saw ads featuring the tagline “Innovation is our focus,” others saw the tagline “Great photos are our focus,” and a third group of participants saw ads without a tagline. All participants were then told that the company had introduced a new camera that uploads pictures wirelessly. After viewing an ad for it, they were asked to rate the camera’s quality.

“For certain products, like cell phones or hybrid cars, it doesn’t matter what brand makes it or what the specifics are, people are worried about them malfunctioning.”

Those who had been primed to think about malfunctioning products—but not participants who had simply written about their week—were much more wary of the innovative brand than of the other brands, ranking its camera as lower quality.

In other words, having a reputation for innovation was detrimental only when people were already thinking about products that had failed them.

When One of Those Things Is Not Like the Others

But consumers do not usually write essays about product malfunction before shopping. What are some real-world conditions where customers might be wary of a product’s ability to function correctly?

One scenario is something marketers call “low-fit brand extension,” which is when companies move into new and seemingly unnatural markets.

“These are products that seem like a stretch for the brand,” Goldsmith explains, coming up with a few fictitious examples, “such as Häagen-Dazs cottage cheese. Why are we wary? After all, Häagen-Dazs is a high-quality brand, and they already make dairy products. Well, we worry that their ice-cream skills aren’t transferable to cottage cheese. The same holds for, say, Heineken popcorn or BMW skateboards. So we predicted that when consumers evaluate products like these, their malfunction risks are already heightened.”

To test this prediction, the researchers recruited 172 undergraduate students and randomly assigned them to one of three groups. All participants read a history of a fictional brand of European shoes that emphasized the shoes’ high quality. For some participants, the history also emphasized the brand’s reputation for innovation.

Participants next rated pairs of the brand’s shoes—both the dress shoes they were known for and a new line of sneakers that was a low fit for the brand—for quality and purchase likelihood.

The results: participants who had been prompted to think about the brand’s reputation for innovation were less likely to purchase the running shoes, but no less likely to purchase the dress shoes.

“We predicted that when consumers evaluate low-fit brand extensions, their malfunction risks are already heightened,” Goldsmith says. “Whereas when they evaluate flagship products they know the brand is good at making, we shouldn’t see these negative effects, and that’s exactly what we find in the data.”

Innovation Can Affect Quality Perception

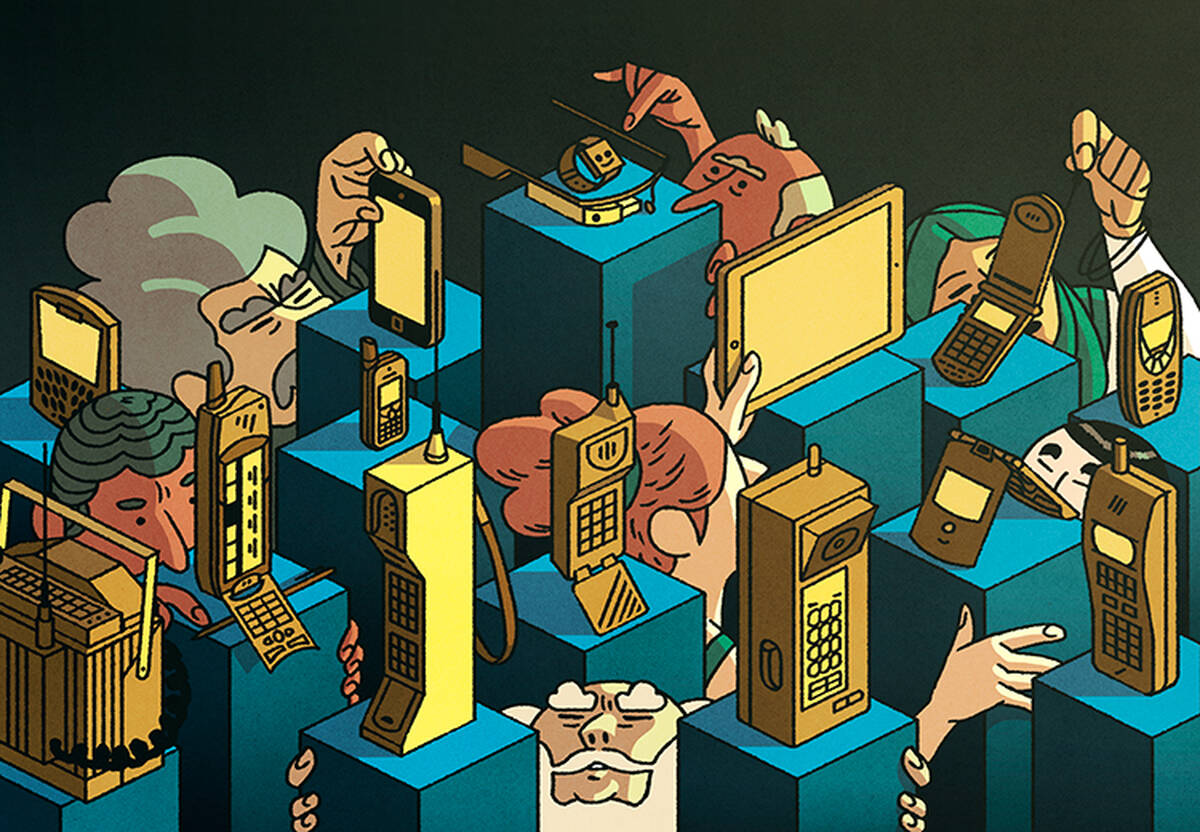

Another real-world scenario: some types of products are simply considered chronically unreliable.

“For certain products, like cell phones or hybrid cars, it doesn’t matter what brand makes it or what the specifics are, people are worried about them malfunctioning,” Goldsmith says.

So how does a reputation for innovation affect how consumers perceive the quality of, say, a cell phone? Does simply marketing a product that is perceived as finicky cause consumers to be wary of innovative brands?

To find out, the authors had online participants read one of four brief histories of the same fictional cell-phone manufacturer: one that focused on the manufacturer’s quality, one on its innovation, one on both, and one on neither. The participants then rated the quality and likelihood of malfunction for four different cell phones from the manufacturer.

Those who associated the brand only with quality gave it high marks, while those who associated the brand with both quality and innovation gave the phones low quality ratings. This pattern was consistent with the researchers’ prediction that, for unreliable products, a reputation for innovation could be harmful.

But—to the authors’ surprise—the participants who associated the brand with innovation only did not rate the phones as lower quality. In other words, having a reputation for innovation hurt the brand only if participants had been primed to also associate the brand with quality.

“We didn’t predict that, going into this experiment,” Goldsmith says. One potential explanation, she says, is that “there are positive associations with innovation if you have nothing else going for you. If you don’t have much of a brand identity, developing an identity for innovation is better than nothing.”

Cognitive Orientation

So if a reputation for innovation can cause problems for brands, why do so many tout it?

“This ties back to the notion that innovation is good in the abstract,” Goldsmith says. In theory, who isn’t interested in having the latest, greatest new product? But when faced with an actual purchasing decision, different priorities may emerge.

To get at this idea, another experiment looked at how people evaluate innovative brands when they are in an abstract versus concrete mindset.

“When you think about abstract, higher-level, big-picture kinds of ideas, concerns about malfunction risk are less likely to come to mind than when you consider the concrete, nitty-gritty aspects of a product,” Goldsmith explains. For example, abstract thoughts about toothpaste might focus on the product’s ability to contribute to dental hygiene, whereas concrete thoughts might focus on the product’s texture.

Previous literature has shown that when consumers evaluate a product on its own merits, they tend to think more abstractly. But when they make purchasing choices between products, they tend to think concretely.

So in this experiment, participants read about two different blender manufacturers. The innovation-focused brand made many design changes over its 25-year history, while the consistency-focused brand rarely changed its design.

Some of the participants then evaluated a variety of blenders from each manufacturer, looking at them one by one. The rest were shown the blenders in pairs and asked to compare them side by side and indicate which they would buy.

Those participants who evaluated the blenders in isolation, and were thus in an abstract mindset, were more likely to prefer the blenders from the innovative brand. Those who did the side-by-side comparison, and were therefore in a concrete mindset, preferred the consistent one.

Taken together, the findings indicate that companies should not be overly eager to jump on the innovation bandwagon, Goldsmith says.

“It seemed odd that no matter what you read in the popular press, people always say innovation is good and important,” she says. “This seems like a very narrow view of innovation.”

Goldsmith, Kelly, Jeffrey S. Larson, and B. J. Allen. Under Review. “When a Reputation for Innovativeness Confers Negative Consequences for Brands.”