Featured Faculty

Professor of Marketing; Associate Professor at Medill School of Journalism, Media, and Integrated Marketing Communications

Harold T. Martin Professor of Marketing; Director of the Center for Market Leadership

Michael Meier

Among French wines, Château Pétrus is legendary. Consumers pay over $1,000 for a single bottle. Talking with Christian Moueix, the owner and long-time winemaker of Pétrus, Kellogg’s Gregory Carpenter asked an innocent question: When crafting a wine, how do you think about the consumer?

Taken aback, the vintner paused, leaned back, and opened his eyes wide. “He said, ‘I don’t! I make what pleases me,’” recalls Carpenter, a professor of marketing at the Kellogg School.

That may come as a surprise to those who think that winning customers requires exhaustive surveys and precise analytics to discover what people want. Yet this consumer-skeptic attitude is common among winemakers. “They suspect that consumers don’t really appreciate and respect wine,” says Carpenter, “so there’s no point asking them what they think.”

But from a business point of view, that presents a challenge: How do you create devoted customers and turn a profit if you essentially ignore what customers want?

Winemakers are not the only ones facing this quandary. Marketing scholars have a term—“market-driving firms”—for businesses that, rather than reacting to consumer tastes, attempt to influence those tastes to their advantage. But prior research on market-driving firms has focused on high-tech innovators like Apple and Tesla. These companies shape consumer preferences by introducing unprecedented products and services, which often render the competition obsolete. As Steve Jobs famously stated: “Our job is to figure out what [customers] are going to want before they do.”

Carpenter wanted to know how a company can influence consumers without a disruptive new technology to offer. So, working with Ashlee Humphreys, an associate professor of integrated marketing communications at Northwestern’s Medill School, he turned to the wine industry. “Winemaking hasn’t changed in thousands of years,” Carpenter says.

“You have to have a vision of what you’re trying to accomplish. That’s what you’re really selling.”

In a new study, the scholars explore how preeminent wineries successfully educate customers rather than catering to customers’ wishes. The researchers immersed themselves in the French, Italian, and American wine industries for five years, interviewing close to 60 people, including CEOs, winemakers, salespeople, marketers, wine critics, distributors, retailers, and consumers. “We went to wine tastings,” says Carpenter. “We went to dinners. We observed consumers in tasting rooms in Napa Valley and, in some cases, we participated in winery events.”

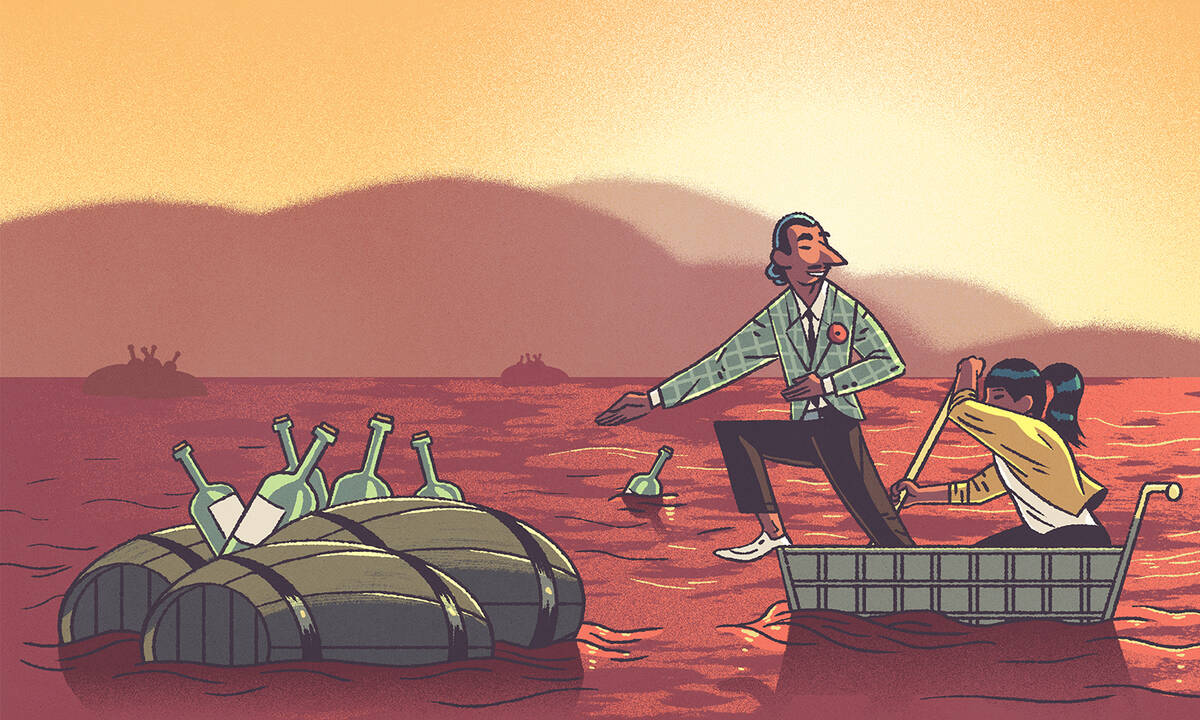

Drawing on that research, Carpenter and Humphreys paint a picture of an industry where brands succeed not simply by making wines that please consumers. Instead, producers strive to make something great and novel—something beyond consumers’ imaginations. They then compete to influence critics, experts, and the media, who in turn shape the tastes of distributors, retailers, and, ultimately, drinkers.

“A consensus develops around who’s doing interesting stuff, and that shapes what consumers think,” explains Carpenter.

This conclusion may be of interest to companies in any industry that seek to influence what customers want. But Carpenter warns that in order to win at this “status game,” brands need a unique, compelling story that sets them apart from all the others competing for the same cultural cachet.

“You have to have a vision of what you’re trying to accomplish,” Carpenter says. “That’s what you’re really selling.”

Many mass-market wine brands (think Barefoot or Yellow Tail, which you can find at any supermarket) follow a traditional business model, making fruity and boozy drinks that appeal to most palates. But Carpenter and Humphreys were interested in how so-called “fine wines” distinguish themselves from their myriad competitors.

As Carpenter read the research on wine, it struck him how perplexing wine can be for consumers—even for connoisseurs.

In one famous study, burgeoning wine experts were given two glasses of wine, one red and one white. The tasters (students in the University of Bordeaux’s winemaking program) described the two wines with completely different language. Little did they know, both glasses contained the same wine—the drink in one glass had simply been dyed red with a tasteless food coloring.

The takeaway for Carpenter: great wines are considered great not simply because they taste extraordinary, but because of what we believe about them. “There are many delicious wines, but few great wines, just like there are many excellent artists but few great ones,” Carpenter says.

So what is the best way to make these easily influenced customers believe that a particular wine is “great”? And how do some winemakers succeed where so many others fail?

From the research, it was clear that winemakers recognize that their customers are not experts. As one vintner told the authors: “People don’t know what they’re drinking, basically.”

Which is why, rather than cater to clients, winemakers make the wines that they want to make, guided more by artistic vision than market forces. Some even admitted to making wines they knew customers would find unpalatable, insisting that the drinkers, not the drink, were at fault, and believing that the customers would eventually see the light.

“The route to success with consumers begins with critics, wine writers, and other winemakers.”

So how can a vintner convince inexpert consumers to choose her wine over the thousands of excellent alternatives? “The route to success with consumers begins with critics, wine writers, and other winemakers,” says Carpenter.

Firms first build relationships with critics and the press, the authors find. A winemaker describes her vision to these individuals, hoping to turn them into advocates for her vision. If she succeeds, a wine writer might award a high score and write a glowing review. From there, another celebrated winemaker might take notice, and decide to endorse her latest vintage.

When these preeminent winemakers and critics praise a particular wine, people listen. The wine soon appears on more retailers’ shelves and more wine lists, earning the attention of salespeople and sommeliers.

Customers then clamor to buy the brand, with the understanding that this is the latest and greatest in wine. “And they share it with other people,” says Carpenter. “So you have this snowballing effect.”

While this process is chiefly driven by elite tastemakers, vintners can improve their odds of success by cultivating a certain ambiance around their wine. The authors describe how wineries often spend big bucks to turn their tasting rooms into enchanting spaces. Additionally, many put on opulent events where they present their winemaker as the visionary behind the brand, adding to its allure.

The story of Dominus Estate, a Napa Valley winery, exemplifies how a wine can be propelled to success. Dominus’s winemaker, Christian Moueix, had crafted celebrated wines in Bordeaux before buying a legendary vineyard in California’s Napa Valley. But rather than make another typical California cabernet sauvignon, Mouiex pursued his own pioneering vision: he wanted to create a distinctly Napa wine in the French style.

He produced his first Napa vintage in 1983. Critics praised the wine, but, at first, neither the press nor fellow winemakers fully understood his approach. “They said, ‘It’s not Californian, not really French—so what is this stuff you’re making?’” says Carpenter.

For the next three decades, Moueix remained devoted to his vision, and graciously explained his concept to fellow tastemakers. Meanwhile, he hired avant-garde architects to build a winery that showcased the natural beauty of the surrounding vineyards, reinforcing his reputation as winemaker with respect for both tradition and change.

Gradually, critics and the press embraced Mouiex’s novel vision. Critics awarded him higher and higher scores. Eventually, in 2013, several prominent critics gave Dominus Estate’s signature red blend a coveted perfect score. In 2016, one critic awarded it 100 points, writing that, “If I could give more than 100 for this one, I would.”

And with that top-shelf reputation has come a swell in demand: today, a single bottle of Dominus Estate can fetch upwards of $300.

The lesson, according to the researchers: companies that succeed in influencing consumer tastes need to have a unique, attention-getting concept that tastemakers can champion. In the case of Dominus Estate, it was, more than anything, Moueix’s groundbreaking idea for a French–Californian hybrid that changed how people think about great Napa wine.

Yet in crowded industries like wine, where many bottles have a bold concept or a clever story printed on the label, selling your vision is no easy task. “It’s extremely hard to be successful,” Carpenter says.

But once a firm successfully shifts tastes, the effects can be remarkably enduring. For instance, in 1855, Napoleon ordered a definitive classification of the finest wines produced in Bordeaux. Only four wines qualified for the top category and, in the 160 years since, only one winery has been added, even though hundreds of renowned producers have attempted to join their ranks. That is a sharp contrast to the tech industry, where new firms often appear and quickly eclipse market leaders, Carpenter explains.

Beyond the wine industry, the study sheds new light on how firms can successfully shape markets without high-tech innovations.

Starbucks, Levi’s, and Chobani have followed this strategy, Carpenter argues. For example, Starbucks founder Howard Schulz set out to refine his customers’ tastes and ended up dramatically shifting the way Americans drink coffee. The study suggests Starbucks succeeded by achieving a certain level of status, which helped win customers’ trust—and because Schulz had a radical, uncompromising vision for what coffee should be.

“People think it’s about making a good product,” Carpenter says, “but it’s about vision.”