Featured Faculty

Harold T. Martin Professor of Marketing; Director of the Center for Market Leadership

Michael Meier

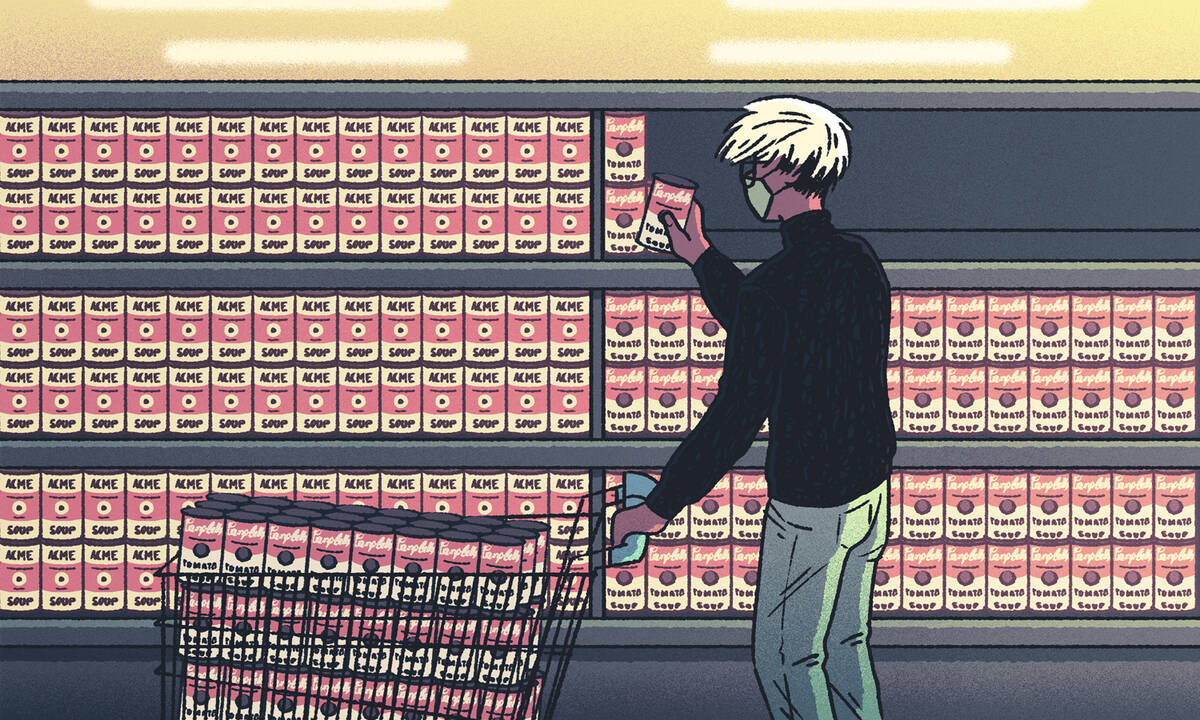

This spring, as COVID-19 infections spread across the country, consumers began making noticeably different choices. Shoppers stripped grocery-store shelves of household staples. Hand sanitizer sold out quickly. And consumers began buying more natural and organic foods, apparently placing healthfulness over price.

At the same time, however, consumers made plenty of choices that weren’t that healthy at all. They purchased dramatically more fallen-out-of-favor brands like Oreos, Doritos, and Campbell’s soup. And consumers developed a renewed hankering for Big Macs and other fast-food favorites. After struggling to attract consumers for some time, McDonald’s stock rose over 50 percent since mid-March. “Has pandemic snacking lured us back to big food and bad habits?” asked an article in the New York Times.

A new paper from Gregory Carpenter, a professor of marketing at the Kellogg School, sheds light on consumers’ seemingly inconsistent response—revealing that the presence of contagious disease increases consumers’ desire for familiar products.

Why? With disease comes disgust as well as fear. Those two emotions together, the researchers found, push consumers toward products they know and trust.

“We’re very good at appearing rational,” Carpenter explains, “but when you take your emotions and stuff them away, they come out in strange ways—and in this case, they come out when you buy cookies.”

Carpenter and his coauthors—Kellogg alum Chelsea Galoni, now of the University of Iowa, and former Kellogg faculty Hayagreeva Rao, now at Stanford—had been studying how disease influences buying behavior for several years before the arrival of the current pandemic. They were interested in how consumers respond to multiple emotions and chose to study disease because it generates powerful, complex feeling.

Until now, most studies on consumer response to disease focused on disgust—in psychological terms, a sense of revulsion that arises from being close to a perceived contaminant. The dominant response

to disgust is to withdraw: people want to get away from whatever gave them that icky feeling. As a result, researchers have speculated that disgust might cause people to buy less overall.

But Carpenter and his coauthors thought there might be more to the story. After all, a significant component of disease, especially contagious disease, is fear. “When someone sneezes on the train, you’re disgusted—but you’re also afraid you might get sick,” Carpenter says. “Your life may be disrupted. But you don’t know if it will or how it will, and you can’t control it.”

Fear promotes an entirely different response than disgust. “When people are afraid, they take action: if you hear a noise in your house, you don’t usually sit there and say, ‘I hope this goes away.’ You go and look,” Carpenter explains.

That’s why Carpenter and his coauthors thought contagious disease might bring about a unique combination of fear and disgust. “It’s not just the disease, but it’s the type of disease,” Carpenter explains.

The loss of control brought about by fear, they thought, would push consumers to take action— in this case, purchasing—which made them feel in control, while the desire to withdraw brought about by disgust would pull them away from anything unknown. As a result, the researchers hypothesized that the presence of contagious disease might lead consumers to prefer products that they view as familiar.

Carpenter and his coauthors put their hypothesis to the test, recruiting a group of 226 online participants from various ethnic backgrounds to complete a short study.

“We don’t think of buying a traditional Oreo as a way to bring control into our life, but that’s apparently how people are behaving.”

— Gregory Carpenter

The participants were divided into three groups: one group read about heart disease, another about the flu, and the control group about the Instant Pot pressure cooker. Then, all participants saw a group of 20 emotion words and rated from one to seven how strongly they felt each one. The list of 20 words included five designed to measure fear, such as “anxious” and “vulnerable,” and four designed to measure disgust, such as “unclean” and “revolted.”

As expected, participants who read about the flu and heart disease identified with fear and disgust words more than those who read about the Instant Pot. The combination of fear and disgust, however, was most pronounced among participants who read about the flu.

Next, participants took a virtual shopping trip: they saw a list of 14 common grocery items and were asked to select the five they would be most likely to purchase. The 14 items appeared to be random, but were actually designed to vary in how familiar they would be to consumers of different cultures. For example, participants were presented with two starches: potatoes (more commonly used in Western cooking) and rice (more commonly used in Asian and Hispanic cuisines).

Again, contagion pushed people toward that which they knew. Participants in the flu group preferred a greater proportion of culturally familiar ingredients than those in the control or heart-disease groups: those who self-identified as European or North American preferred the products more familiar to Westerners, while those who self-identified as Asian or Hispanic preferred the other products.

Still, from the first experiment, an important question remained. The researchers couldn’t be sure whether the preference for familiar items was being driven by the combined effects of fear and disgust, as they believed, or whether it was instead driven by one of the emotions on its own.

So in their next test, Carpenter and his coauthors were careful to disentangle fear and disgust. A new group of 600 online participants was asked to imagine an outbreak of shingles in their city.

Half of the participants read about the unpleasant visible symptoms of shingles, such as blisters and scabs, while the other half read about its internal effects, such as muscle aches and fever.

Shingles isn’t contagious, but many people think it is—a fact the researchers used to their advantage. Once again, participants were divided into two groups, with half reading shingles can be spread person-to-person, and the other half reading it can’t.

This created four groups of participants: a visible-symptom/contagious-disease group, a visible/noncontagious group, a non-visible/contagious group, and a non-visible/noncontagious group.

The researchers knew from an experimental pretest that contagious diseases provoke more fear than noncontagious diseases, and that visible symptoms provoke more disgust than non-visible symptoms. So if their theory was correct—that fear and disgust combined have a different influence on consumer behavior than fear or disgust alone—then the group who read about visible symptoms and contagion should exhibit noticeably stronger preferences for familiarity than the other groups.

All four groups read about a newly released set of headphones. For half the participants, the headphones were described as familiar and trusted, while for the rest, the headphones were described as novel and innovative. Then, participants rated from one to seven how much they liked the headphones and how likely they were to buy them.

As predicted, participants in the visible-symptom/contagious-disease group—that is, those who experienced both disgust and fear together—showed the most marked preference for the familiar over the novel.

Would the results of these carefully designed experiments hold true in the wild, where our choices are more idiosyncratic and unpredictable?

To answer that question, Carpenter and his coauthors used data from Nielsen, which collects very detailed information on consumer purchases. They also used data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and from Google’s Flu Trends tool to estimate the presence of influenza in each state over every week from January 2009 to December 2014. They opted to focus on the flu because it’s widely publicized, highly transmissible, and carefully monitored by public-health officials—making it a good way to test the effects of contagious disease on consumption. (While the coronavirus also fits this bill, the study was conducted before the coronavirus swept across the U.S.)

Then, the researchers looked at all weekly sales of canned soup and Oreo cookies during the same time period. For soup, they considered the leading national brand, Campbell’s, as familiar and all other canned soups as less familiar. For Oreos, they treated the traditional sandwich cookie as familiar and its more exotic variants—Mint Oreos, Oreo Thins, and so on—as less familiar.

Not surprisingly, soup purchases increased overall as the levels of flu increased. But this trend particularly benefited the familiar brand, Campbell’s, which saw a significant sales bump as flu levels rose: a 10 percent increase in flu was associated with a 1.6 percent increase in sales for Campbell’s—but only a 0.1 percent increase for other brands.

Soup is a classic home flu remedy, so the researchers couldn’t be sure whether this pattern was a response to disgust and fear, or to the perceived medicinal properties of soups.

So they tested the relationship again with another food with no healing properties: cookies.

As expected, there was no relationship between overall Oreo purchases and the presence of flu in a given state in a given week.

But there was a preference for traditional Oreos over newer versions of Oreos as flu increased: a 10 percent increase of flu was associated with a 0.61 percent increase in sales of familiar Oreos and a 0.44 percent decrease in sales for unfamiliar Oreos.

It was exactly what the experiments predicted would happen: as consumers contended with greater levels of flu, they fought back against those feelings by seeking out products that helped them restore a sense of control and familiarity.

“We don’t think of buying a traditional Oreo as a way to bring control into our life, but that’s apparently how people are behaving,” Carpenter says.

Carpenter says the research offers some important lessons for marketers trying to adapt in response to COVID-19. “Innovation is going to be really tough,” he says. Instead, it’s a great time for brands to go back to basics.

Some companies are already doing just that: McDonald’s reduced its menu to core items such as burgers, fries, and soft drinks. At a difficult time for fast food businesses, the chain saw its drive-through business explode—and reported higher customer satisfaction with the more streamlined menu.

Carpenter says it’s a good case study for brands grappling with the effects of COVID-19: “Focusing on what you do best, the brands customers trust, and simplifying your operations has a real advantage in this time.”