Featured Faculty

Gordon and Llura Gund Family Professor of Entrepreneurship; Professor of Strategy; Co-Director of the Ryan Institute on Complexity; Professor of Economics (Courtesy)

The degree to which leaders matter is an old and unsettled question. Despite centuries of thought and study, this issue remains divisive. What none can doubt, however, is this: leaders die. And when they do, national economies can change in major, unexpected ways, according to research by Benjamin Jones, assistant professor of management and strategy at Kellogg, and his colleague Benjamin Olken (Harvard Society of Fellows).

Their report in The Quarterly Journal of Economics provides clear evidence that unpredictable changes in a country’s leadership, due to the executive’s death by accident or illness, can trigger changes in gross domestic product (GDP) growth. In this new light, the grip of massive political institutions on economies appears much less commanding than was previously thought.

Economists, historians, and political scientists have long debated the role of leaders. Marx argued that leaders can merely choose from options that are strictly limited by factors far beyond their control. Even more dismissive was Tolstoy, who saw leaders merely as artifacts, their importance contrived after the fact to explain events completely beyond their influence. Through such eyes, the “Great Men” of history, as observed by Thomas Carlyle, are nowhere to be seen.

This is not to say that great, or at least idiosyncratic and influential, individuals have been completely discredited as engines of change. The British historian John Keegan attributes the political history of the twentieth century to six men: Lenin, Roosevelt, Churchill, Hitler, Stalin, and Mao. Straddling the chasm between the extreme, all-or-nothing views of leadership, Max Weber and others proposed shifting balances of institutions, social pressures, and “charismatic” individuals as drivers of history.

While serving as special assistant to the deputy secretary of the U.S. Department of the Treasury, Professor Jones saw firsthand how individuals, charismatic or otherwise, could wield enormous influence over the organizations they led. But the quasi-monarchic leaders he saw scattered about the government and the globe had not captured the full and prolonged attention of academic economists.

“The study of leaders as important fixtures in understanding growth is underrepresented in the economics literature, which mainly emphasizes social and technological forces,” said Jones. “Economists would have given leaders room for influence, but assumed that they wouldn’t have much effect.”

“The study of leaders as important fixtures in understanding growth is underrepresented in the economics literature, which mainly emphasizes social and technological forces,” said Jones.

As he became increasingly interested in the study of human capital and investment in individuals, Jones wanted to understand mechanisms and limits of individuals’ influence on large-scale phenomena. He wondered, “Would those influences aggregate upwards to impact the growth of an economy?”

To test the power of leaders, Jones and Olken collected data on all national leaders worldwide since World War II and paired it with the Penn World Tables, a database of global economic information. They found descriptions of 1,108 different leaders from 130 countries, covering essentially every nation from 1945 to 2000. Cancers, heart attacks, strokes, and deaths by other natural causes took sixty-five of those leaders while in office. Another twelve died in accidents fiery, watery, and even equestrian.

In order for their analyses to truly reflect unique effects of individual leaders, Jones and Olken had to ensure that the deaths were random and not related to underlying features of the economy. For this reason, they were careful to exclude the twenty-eight leaders who were assassinated, since such deaths are often related in some way to political and economic factors. Of the seventy-seven leaders who died but were not assassinated in office, twenty could not be studied due to a lack of sufficient economic data, leaving Jones and Olken to focus on fifty-seven leaders.

Having identified these randomly deceased leaders, Jones and Olken measured what effect, if any, these upheavals in leadership had on national economies. They devised empirical tests to evaluate yearly measures of average personal income, comparing economic changes over periods of three to seven years before and after the fifty-seven deaths. If leaders had impacts on their nations’ economies, the models would detect differences in economic growth between pre- and post-death periods.

The effect of leaders on growth was substantial. Economies were measurably disturbed and unsettled far more than normal following unexpected leadership transitions. A measure of variation in growth showed 31 percent more variability following leaders’ deaths than would normally be expected.

But what is a national leader without a nation to lead? Might some nations be more willing or able than others to resist their leaders’ influence? Recognizing that social and political circumstances could have a profound impact on leaders’ economic influence, Jones and Olken dissected their data further. They studied whether differences in government, income, and ethnic fragmentation affected economies’ resilience in the face of leadership change.

Not all types of government are equally sensitive to random changes in leadership. Democracies, in which executive influence is typically moderated by independent legislative and judicial powers, appeared insulated from individuals’ influence on GDP. But leaders’ deaths triggered substantial economic change in autocratic countries, which typically had limited competition for leadership and imposed few constraints on the executive. Particularly vulnerable were autocracies with no political parties and those whose leaders had assumed power via coup d’etat. In short, leaders mattered most when institutions mattered least. Compared to these effects of government, patterns of poverty and ethnicity within a country had little or no effect on growth.

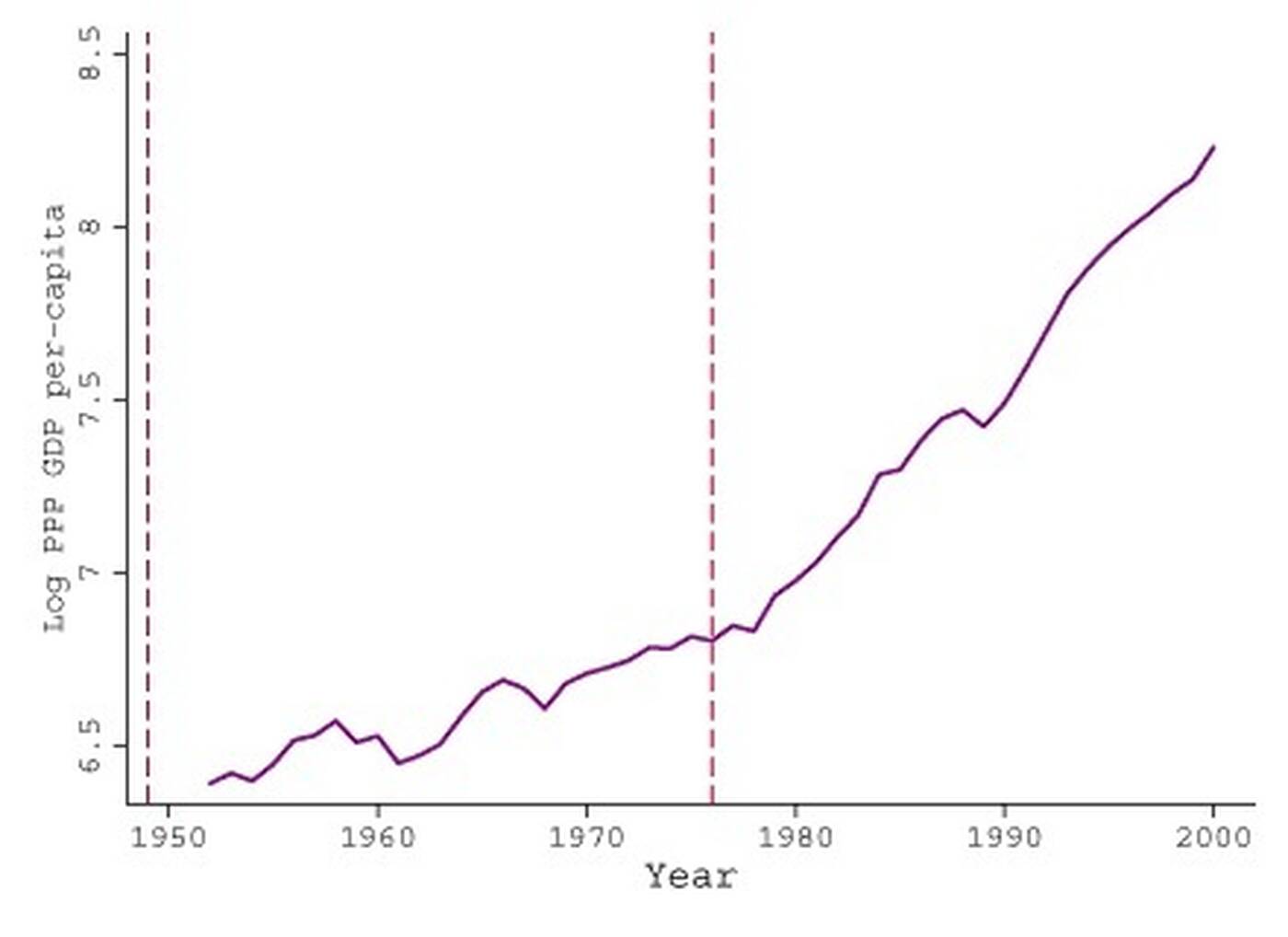

The effect of leadership on growth, while dramatic in autocracies, was not consistently good or bad. Some leadership transitions amplified or minimized trends that already existed while others triggered dramatic reversals. Some economies expanded and others shrank. Following Mao’s death in 1976 (see Figure 1) China’s growth reached 5.9 percent annually. This was nearly triple the more modest 1.7 percent yearly growth prior to his death. In stark contrast to the Cultural Revolution and other policies that likely retarded growth under Mao, his successor, Deng Xiao-Ping, is widely credited with moving China toward market-oriented policies.

Growth in Mozambique (see Figure 2) changed course entirely following the 1986 plane crash that killed Samora Machel. A Communist Frelimo guerrilla, Machel nationalized all private land as president of his one-party state. Persistent shrinking of the economy ensued, averaging a 7.7 percent annual decline in GDP. The multi-party, freer-market tenure of Joaquin Chissano reversed the shrinkage from Machel’s rule while averaging 2.4 percent growth each year.

“To see effects in such a large measure as economic growth was surprising to us,” said Jones. “We thought we would see effects only among a subtler set of policies.”

Jones and Olken then looked at subtler policies, seeking to identify particular economic factors susceptible to leaders’ influence that could help explain large-scale changes in growth. They studied the roles of monetary, fiscal, trade, and security policies. To do this, they measured rates of inflation, government spending, international trade, and armed conflict, respectively.

Autocratic leaders, presumably more critical than central banks in setting monetary policy, influenced inflation rates. Other research by Jones and Olken suggests that leaders’ deaths triggered changes in the money supply. There is little evidence, however, that individual leadership affected fiscal, trade, and security policies.

That this research discovered any influence of individuals on national economic measures is notable. But to find that an individual could manipulate something as substantial as GDP is transformative. This work points to possible mechanisms behind the often-sharp changes in growth in developing countries. It also recasts social and political institutions in less consistent roles as agents of economic development. Democracies may be able to protect countries from economic disasters such as those suffered in Zimbabwe under Mugabe, but they may also handcuff successful policies such as those put forth by Deng Xiao-Ping in China.

Their interest piqued and their data still fertile, Jones and Olken are continuing their research on leaders, death, and national transformation. They recently presented their new work, “Hit or Miss? The Effect of Assassinations on Political Institutions and War,” at the annual meeting of the American Economic Association. This new paper, like their previous one, shows how seemingly trivial randomness, such as cancer mutations and twitching trigger fingers, can alter the course of history.

Further reading:

Jones, Benjamin F. and Benjamin A. Olken. ”Hit or Miss? The Effect of Assassinations on Political Institutions and War.” Working paper presented at the annual meetings of the American Economic Association, Chicago, January 2007.

Keegan, John (2003). “Winston Churchill,” Time Magazine

Weber, Max (1947). The Theory of Social and Economic Organization. New York: Free Press.