Leadership Feb 27, 2021

Executive Presence Isn’t One-Size-Fits-All. Here’s How to Develop Yours.

A professor and executive coach unpacks this seemingly elusive trait.

Lisa Röper

In her work as an executive coach, Brooke Vuckovic says there’s one topic that comes up with almost every single client: executive presence.

But, Vuckovic says, even though we so often talk about wanting to improve our executive presence, “we don’t quite know what it means when we’re pressed to define it.”

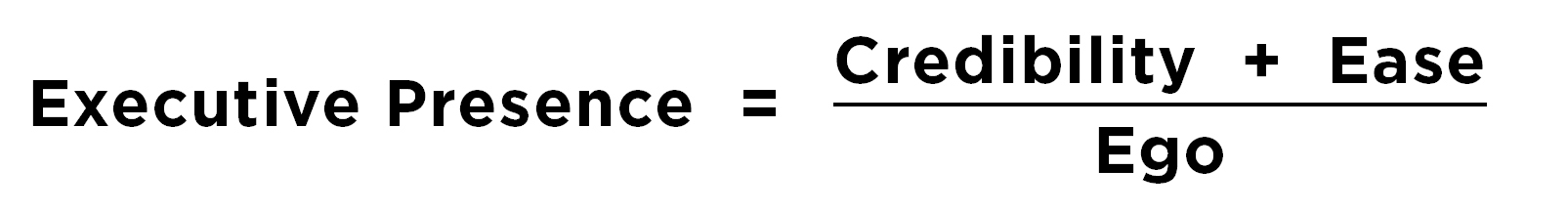

So Vuckovic, a clinical professor of leadership at Kellogg, created a rough formula for executive presence:

She stresses that while these underlying components are universal, a strong or effective executive presence might look different from one individual, situation, or culture to the next. So she encourages people to think of the pieces that make up these components as dials on an instrument panel. Depending on the circumstance, you can turn some dials up and others down.

“This is not a template, one-size-fits-all formula,” she says. “It is a flexible formula that you can tailor to your needs and the needs of your organization and your team at a particular time.”

During a recent The Insightful Leader Live Webinar, Vuckovic broke down each of the formula’s components and explained how leaders can improve on each dimension. Below is a sampling of her advice (we did an Insightful Leader podcast breaking down her points, too.).

Credibility

Each component of executive presence is composed of a number of factors.

With credibility, one piece is simply expertise in your role. “Especially early on in your career, intellectual horsepower is essential,” she says.

Along with expertise, credibility can be boosted with preparation and by exhibiting integrity.

But, of course, you need to be able to communicate your credibility to others. So once you’re sure you know your stuff, how can you work to better convey that? Vuckovic offers a few tips.

For starters, avoid a monotone delivery. (For those who struggle with this, she suggests practicing inflection by reading children’s books aloud.) Try not to talk too fast, which can convey nervousness or even the desire to “pull a fast one” on an audience. And do your best to avoid using too many filler words—“er,” “um,” “uh”—which can be distracting from the message you’re trying to convey.

Additionally, make sure you aren’t fidgeting or using “props” in a meeting. This means no knee bouncing, no pen clicking, no beard stroking or hair twirling, and definitely no phone checking. “The question I like to ask is, ‘what are you in relationship with more than the people in the room?’”

Overall, Vuckovic says, “credibility has the largest number of dials in the instrument panel, and they are the easiest for you to turn and adjust.”

Ease

As with credibility, ease also has several foundational elements. These include making sure you are eating and sleeping well, have social support, and are making time for movement in your day. These things will help build your capacity for resilience under stress.

Vuckovic points to a few key ways to maintain and convey ease.

One involves “emotional agility,” or the ability to manage your feelings, particularly in difficult situations. She stresses the importance of being able to describe what you are feeling in a moment of stress. “As psychologists say, ‘when you name it, you tame it.’”

So, instead of simply sensing that you’re angry, or worse, starting to yell or pound the table, you would instead mentally note what you’re feeling in your body. Vuckovic explains what that may sound like: “’My heart’s racing. I can feel my face is getting flushed. My hands are sweaty. My stomach is getting knots.’ You simply start to describe the physical sensations that are occurring at that time and your central nervous system will de-escalate and calm down.”

Other ways to convey ease include connecting with those you work with, which can mean listening well and maintaining eye contact, as well as authenticity, which signals “a sense of self-assurance.”

Ego

With ego, Vuckovic says, “what we’re looking for is true confidence and true humility.” This means demonstrating that you believe that you have something to contribute—and that you believe other people do, too.

With ego being the denominator in the executive-presence formula, Vuckovic points out that you don’t want to have a miniscule ego, nor do you want an oversized one, since both a negative number and a giant number will mean an erosion of the credibility and ease that you’ve worked to convey.

One tip for both reigning in large egos and boosting small ones: stop thinking about yourself too much. For outsized egos, this introduces more humility into your presence. For small egos, the advice is a little less intuitive. But Vuckovic points to research into underrepresented minorities and women, who may struggle with their own sense of worth in an organization. “When they worry less about what people are thinking about them and how they’re assessing them, and focus more on their purpose, their values, their contributions, why they do the work they do, they typically fare better both in terms of how they’re evaluated as well as releasing some of that psychological weight of considering how other people are assessing them.”

Vuckovic says that for everyone, a focus on doing good work is what will ultimately determine how your peers or your boss or you clients think of you. No level of executive presence can compensate for a lack of ability. But, she says, it’s crucial to display executive presence if people haven’t yet had a chance to evaluate you based on your work.

“These elements of presence are particularly important when you are interacting with someone for the first time or on a superficial level or you just see them quarterly for client meetings,” she says. On the other hand, “those people around you will have a much more complete picture and, ultimately, are going to judge you by the quality of your work and contributions.”