Policy Healthcare Mar 1, 2025

Investors Are Gobbling Up Smaller Medical Practices. Should Regulators Be Concerned?

These under-the-radar transactions have driven up the price of anesthesia by about 30 percent.

Yifan Wu

For over a century, antitrust laws have prohibited the monopolies, cartels, and anticompetitive mergers that defined the “robber baron” era of American capitalism. But in the past two decades, new kinds of deals that fly under regulators’ radar have become increasingly popular, including “rollups.”

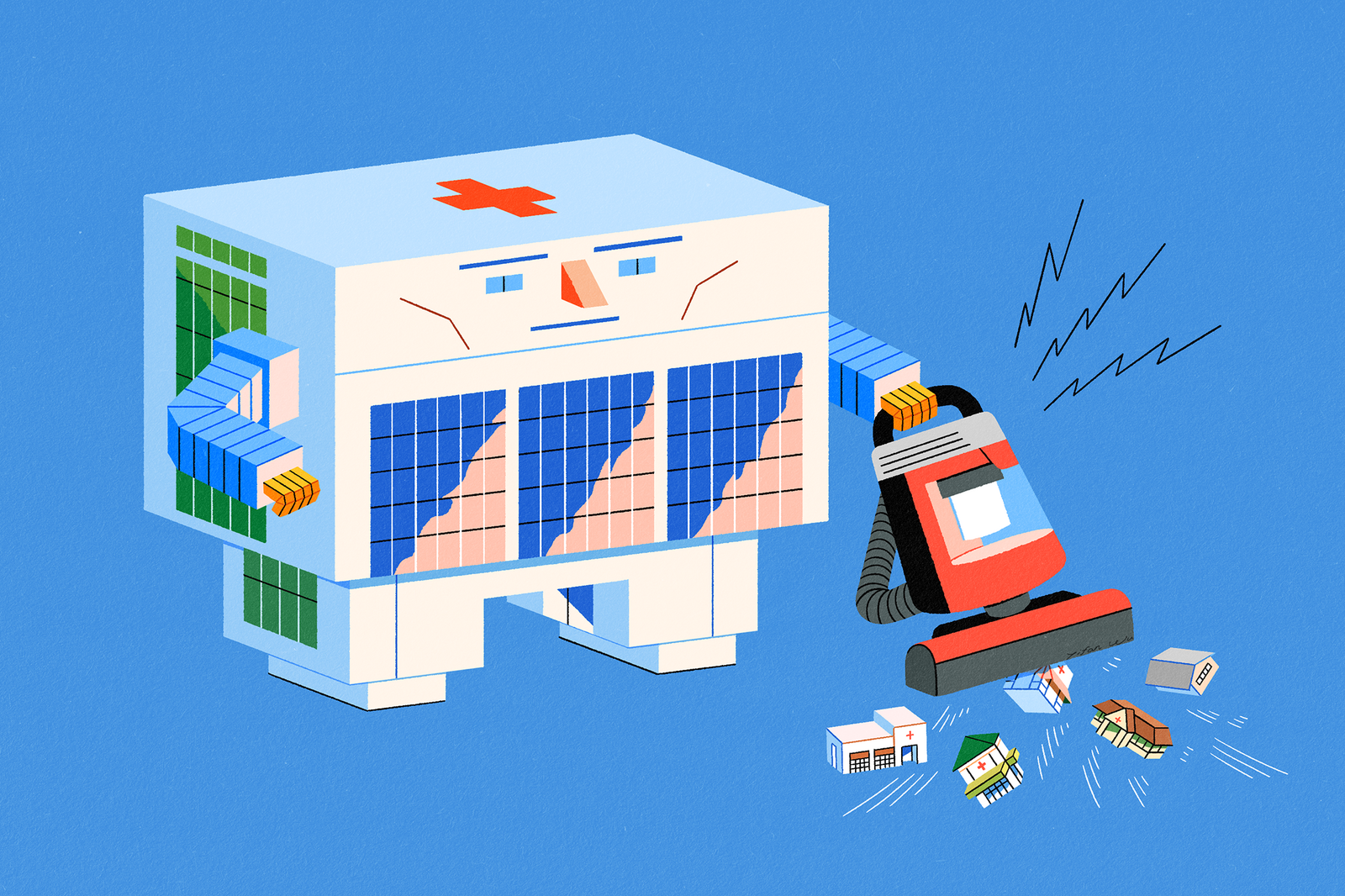

The logic is simple. Instead of one enormous company engulfing another—like AT&T’s 2018 acquisition of Time Warner, which the U.S. Justice Department attempted to thwart—a sponsor uses one firm as a base for acquiring a series of smaller firms in the same market. These smaller transactions each fall below the threshold of what must be reported to regulators. And once enough of them are consolidated, the result is the same as any other large merger.

Similar transactions now account for more than 80 percent of the deals done by U.S. private equity firms—a volume worth more than $1 trillion annually. Should regulators be concerned?

To find out, Kellogg associate professor of strategy Amanda Starc worked with Aslihan Asil of the Yale School of Management and Paulo Ramos and Thomas G. Wollmann of the University of Chicago to model how consolidation affected the market for medical anesthesia.

“Investors go in and buy the biggest [anesthesia] practice in town, and then subsequently buy up smaller practices,” Starc explains. “We’re asking: What is the impact on consumers?”

The answer, according to the researchers, is a decrease in competition that leads to a 30 percent increase in prices.

“This is a tale as old as time: mergers take away options, and that leads to higher prices,” Starc says. “The anticompetitive consequences are very similar.”

These anticompetitive consequences mean that existing antitrust laws can be used to combat the rise of so-called “rollups.” The researchers’ economic model shows that court-ordered “unwinding” of these transactions could reduce hospitals’ anesthesia expenses by nearly a quarter of a billion dollars per year.

“One in five Americans lives in a market affected by these [anesthesia] rollups,” Starc says. “This isn’t some loophole that one guy found—this is a concerted strategy on the part of several firms, and it’s nationwide.”

Rolling up the competition

Before they could analyze how consolidation affected the anesthesia industry, Starc and her collaborators needed to find the anesthesiology practices being targeted—and figure out what they were charging.

“Tracking down who owns what is not trivial, because they’re not trying to be transparent,” Starc explains. “Your friendly local practice does not say, ‘Greater Houston Anesthesiology, brought to you by [private equity firm] Welsh, Carson, Anderson & Stowe.’”

By cross-referencing lists of publicly available data, the researchers created a sample of roughly 9.6 million individual claims for anesthesia procedures. The actual cost of each procedure was linked to the practice that performed it, as was whether that practice was the target of an acquisition between 2012 and 2021. The anesthesiology rollups—in which there are at least two transactions with a financial sponsor—were located in 18 regional markets, covering about 20% percent of the U.S. population.

“One in five Americans lives in a market affected by these [anesthesia] rollups.”

—

Amanda Starc

With this data, Starc and her coauthors compared the average price of an anesthesiology procedure before a rollup with its price after a rollup. Prices jumped nearly 15 percent in a single quarter following a rollup; two years later, they were 30 percent higher.

“Prices go up dramatically,” Starc says. “Everything was flat before the time of the acquisition, but it goes up overnight, and then drifts upward from there.”

Importantly, these price jumps didn’t occur right after a private-equity group acquired a single practice in a geographic market. The price increases only happened for subsequent “add-on” acquisitions. To the researchers, this pattern indicated that the price jumps were a result of lowered competition.

“It’s sometimes called an ‘internalization of business-stealing effects,’” Starc explains. “Let’s say I own Pepsi and you own Coke, and we merge. If I’m thinking about increasing the price on my bottles of Pepsi, a consumer might switch to Coke. But if I also own Coke, I can just set [both] prices to maximize joint profits.” Anesthesiology rollups have the same effect, she says. Owning just one practice doesn’t create an incentive to raise prices. But owning several does.

Rolling back the rollups

The researchers also used the data to create a model of economic incentives within the market for anesthesia services, which helped them better understand price bargaining and let them simulate potential ways to prevent unfair price hikes. Classic antitrust laws provided a good starting point.

“You don’t need a brand new tool to address this,” says Starc. “It’s a competition problem, so it needs a competition-law solution.”

The most straightforward antitrust remedy is “unwinding,” or forcing consolidated firms to reseparate into independent practices. When the researchers simulated the approach of unwinding rollups in their model, prices for anesthesia services fell by between $2 million and $22 million per year, depending on the market—creating a total annual savings of $120 million for the hospitals that pay for these procedures.

Forcing merged companies to unwind also creates a strong incentive for other firms not to put themselves in regulators’ crosshairs in the first place. When Starc and her collaborators simulated this “deterrence” condition in their model, they found that it generated an additional savings of $126 million per year in anesthesiology costs.

More visibility for regulators

To Starc, this analysis shows that this type of consolidation is clearly a problem—“bad for America.” But the solution is clear, too.

“We don’t need to change any laws, but we might need to change the reporting requirements” for mergers, Starc says. Under current regulations, mergers valued under $80 million don’t need to be reported to the FTC in advance—and that threshold can be as high as $320 million under certain conditions. “More visibility into what’s going on with these small deals should help [regulators] analyze them more effectively,” she says.

Beyond that, regulators may just need to flex their muscles more. “There’s under-enforcement going on,” Starc says. “Prices for anesthesia have gone up as a result, and we should expect that to be passed on [to patients] either in the form of out-of-pocket cost or higher premiums. It’s not like we need a full-scale rewrite of the Clayton Act here—we basically need to enforce what’s on the books.”

John Pavlus is a writer and filmmaker focusing on science, technology, and design topics. He lives in Portland, Oregon.

Asil, Aslihan, Paulo Ramos, Amanda Starc, and Thomas G. Wollmann. 2024. “Painful Bargaining: Evidence from Anesthesia Rollups.” NBER Working Paper No. 33217.