Organizations Politics & Elections Sep 28, 2023

It’s Election Season. Here Comes the Morally Charged Language.

In the U.S., presidential candidates across the political spectrum lean on value-laden rhetoric—but emphasize different values.

Yevgenia Nayberg

What made Joe Biden, Jeb Bush, Bernie Sanders, and Donald Trump so different as presidential candidates?

One obvious answer is policy: as candidates, all four individuals had sharply divergent visions for the future of the country.

But new research from William Brady, an assistant professor of management and organizations at the Kellogg School, highlights another important way U.S. presidential candidates set themselves apart from one another: moral language.

The study—coauthored by Kobi Hackenburg of the University of Oxford and Manos Tsakiris of the University of London—draws on analyses of candidate tweets from the 2016 and 2020 elections. It reveals that Democrats and Republicans both lean on morally charged language but do so in very different ways.

“Specifically,” Brady explains, “Democratic politicians tend to really emphasize care and fair treatment, whereas Republicans tend to focus a lot more on things like in-group loyalty and respect for social hierarchy.”

Understanding these contrasting values sheds new light on today’s highly polarized politics. “We’re seeing some of the origins of why Democrats and Republicans see the world in fundamentally different ways,” Brady says. “They’re being fed this rhetoric that is appealing to very different values.”

Democrats and Republicans make contrasting moral appeals to voters

While there are many ways to think about morality, the researchers relied on an approach called moral foundations theory, which hypothesizes that different moral systems across cultures draw from a shared group of fundamental themes: care, fairness, loyalty, authority, and sanctity.

They wanted to know: Would candidates from the two political parties emphasize different themes?

To find out, the researchers gathered 139,412 tweets sent by 39 major-party candidates in the 2016 and 2020 elections. (While 2016 saw more Republican candidates than Democrats, the reverse was true in 2020. Using tweets from both election cycles allowed the researchers to analyze similar numbers of candidates from each party.)

Then the researchers turned to the Moral Foundations Dictionary, a tool developed and validated by other researchers, to analyze the value-laden language used by the candidates in their Twitter posts. For instance, the word “together” is categorized as a loyalty term, while “bless” is categorized as a sanctity term. (Value-laden language does not have to be positive; the word “liar,” for example, was categorized as a fairness term.)

“We’re seeing some of the origins of why Democrats and Republicans see the world in fundamentally different ways. They’re being fed this rhetoric that is appealing to very different values.”

—

William Brady

On average, the researchers found, Democrats used more terms related to care and fairness than did Republicans. They also tended to talk about these ideas in very similar ways to other Democrats, using words such as “justice” and “equity.” Republicans, by contrast, talked more about loyalty, authority, and sanctity, but candidates’ specific language varied slightly more widely—a pattern partly driven by Trump, whose singular moral language set him apart.

Interestingly, Brady notes, the analysis highlighted how little changed in Democrats’ moral appeals between 2016 and 2020. Candidates talked about care and fairness in roughly the same proportions in both elections. Despite losing in 2016, “their rhetoric really didn’t change—it was just ‘rinse and repeat’ and hope that people hated Trump enough.”

Mapping moral language

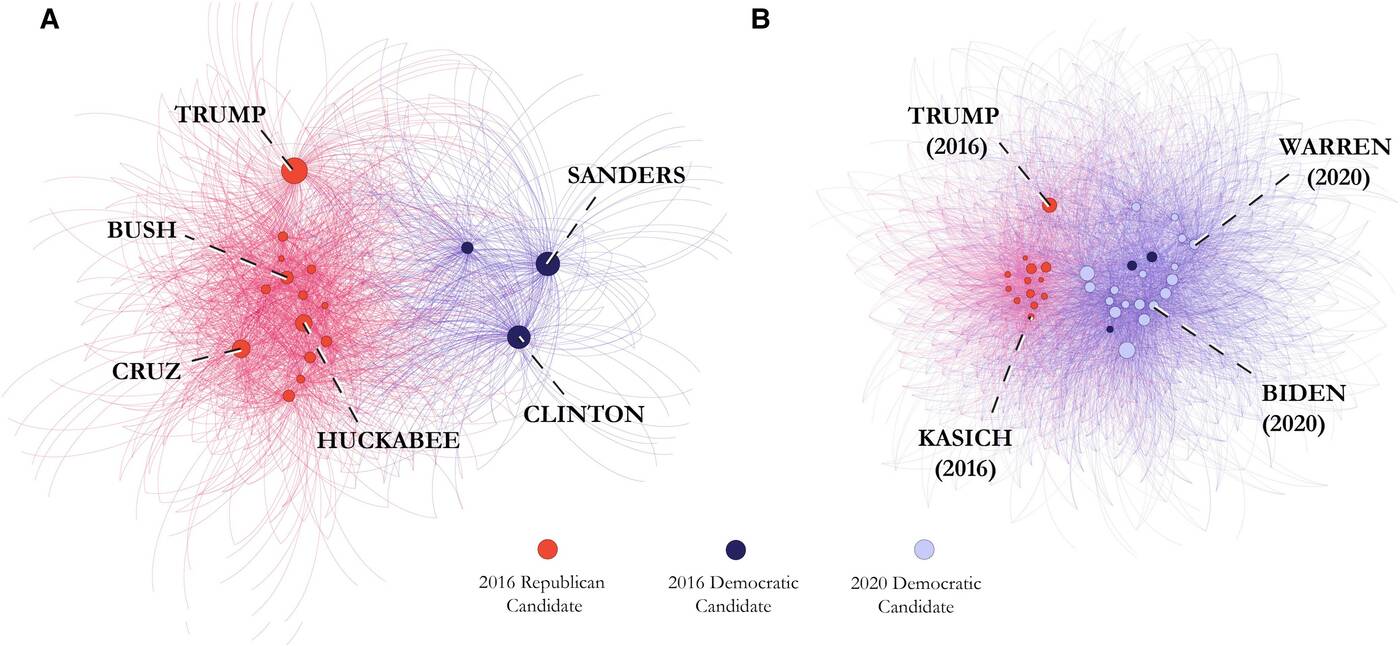

The researchers also used a technique called network analysis to examine the moral rhetorical relationships among candidates. They drew on the same set of moral language from candidate tweets to create visual representations of both the 2016 primary and the combined 2016 and 2020 primaries, with lines between candidates representing shared terms, and distances between candidates representing the degree of similarity in their moral-language usage. The maps reveal two distinct clusters that correlate neatly to political party—a clear sign of how deeply divided even moral discourse has become.

The maps also reveal surprising intraparty differences. In terms of moral language, “Trump is much farther apart from Cruz than Sanders is from Clinton,” Brady notes. This finding, while consistent with the overall trend of Democratic similarity, was also surprising, given that the Sanders–Hillary Clinton battle was seen as a foundational conflict between two wings of the Democratic party, while the ideological differences between Trump and Ted Cruz were seen as comparatively smaller.

“These are things this method allows us to start to look at,” Brady says. “It’s interesting to consider—what would have happened if Bernie had distinguished himself more from Clinton? These are all questions this graph brings up.”

Unique approaches

A few candidates stepped outside of their party’s typical moral rhetoric, the researchers found. In 2016, for instance, Trump talked a lot about one of the Democrats’ signature values—fairness—but used terms unique to him, such as “liar,” “dishonest,” and “biased.” (Of course, he also talked about Republican values in different language than his party mates, making him an outlier in every sense.)

Meanwhile, candidates including Biden, Pete Buttigieg, and Marianne Williamson discuss traditionally Republican values more frequently than other Democrats—sometimes using the same terms as Republicans and sometimes with their own language. For instance, Biden and Williamson talked about sanctity using words such as “prayers” (a Republican favorite) and “soul” (not widely used by GOP candidates). Buttigieg centered his campaign on a non-Republican term related to loyalty: “belonging.”

“This shows you the different rhetorical strategies that candidates used,” Brady says. “Trump was trying to stand out. Biden was just trying to distinguish himself from Trump and seem like a mainstream Democrat.”

The chicken-and-egg problem of diverging values

All of this raises the inevitable question: Are Republicans and Democrats appealing to different values because their voters already believe different things, or is the divergent moral rhetoric actually creating

the divide?

Brady thinks it’s probably some of both. It’s reasonable to assume that Republicans and Democrats probably do prioritize different values. However, “one of the things that we find in a lot of research, including some of my own, is that people, especially in the last 10-plus years, really overestimate the policy and moral differences between themselves and the political outgroup,” he says. The moral rhetoric of candidates and other party elites may well be shaping or deepening this important misperception.

But candidates could also turn down the temperature on polarization—and win support—by adjusting their moral rhetoric. “There’s some work suggesting that when you make appeals in the moral-value frames that partisans are comfortable with, it’s more likely to be persuasive,” Brady says. In other words, the approach of trying to find a Democratic way to talk about traditionally Republican values (and vice-versa) may be effective and good for the nation. As Brady puts it, “what are the shared value frames that candidates could really leverage to try to bring people together?”

Susie Allen is the senior research editor of Kellogg Insight.

Hackenburg, Kobi, William J. Brady, and Manos Tsakiris. 2023. “Mapping Moral Language on US Presidential Primary Campaigns Reveals Rhetorical Networks of Political Division and Unity.” PNAS Nexus.