Organizations Politics & Elections Apr 10, 2023

Are People on Social Media Actually That Outraged?

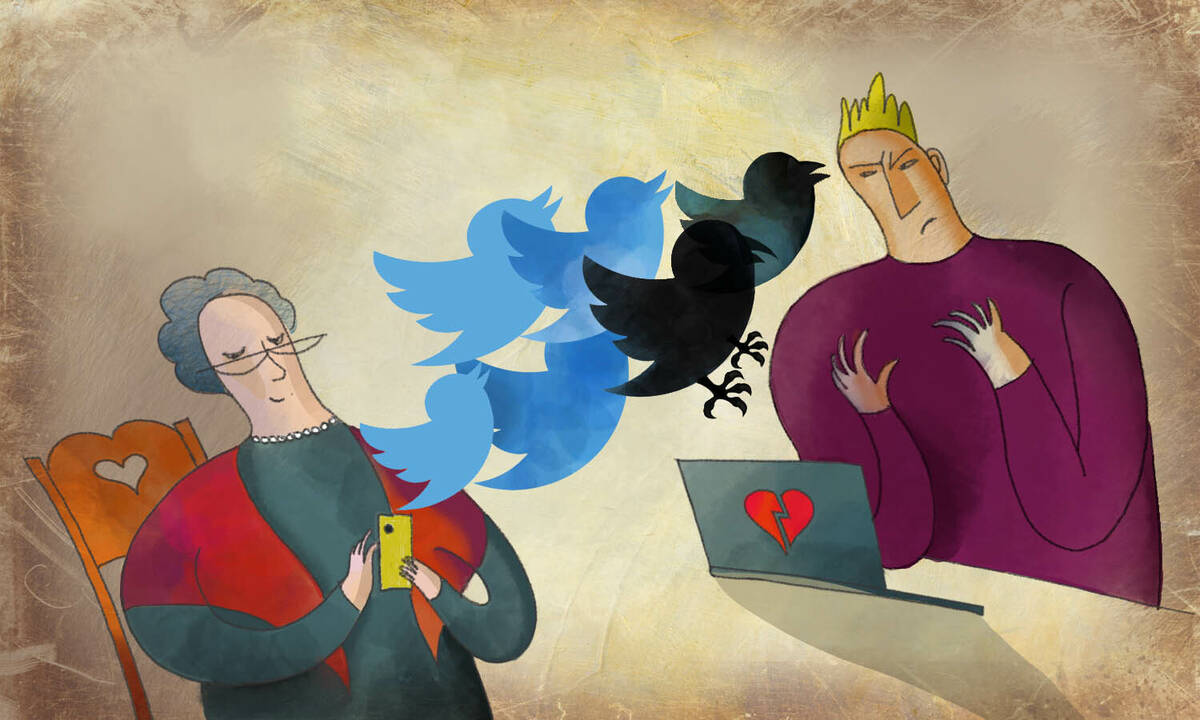

One reason we think Twitter is such a polarized place: we’re bad at inferring how angry people are from their posts.

Yevgenia Nayberg

Have you ever gotten a text message from a friend that felt a little lackluster and wondered, “wait, are they mad at me?”

You aren’t alone. Misunderstandings abound in digital communication, where “there’s limited information richness compared to face-to-face interaction,” explains William J. Brady, an assistant professor of management and organizations at the Kellogg School.

New research by Brady and coauthors shows that the same basic principle applies to interpreting the emotions of people posting on social media. Specifically, the study finds that people perceive greater moral outrage in political posts than authors felt when writing them. This is particularly true for people who regularly use social media to learn about politics.

This skewed outrage detection—a kind of large-scale “wait, are they mad at ... everyone?”—has important downstream consequences, the researchers discovered. Overperceiving outrage in their feeds causes people to overperceive outrage on the social media platform as a whole and increases people’s belief in the ideological extremity and political polarization of other platform users. In other words, when we’re seeing outrage that wasn’t intended and may not be there, the misunderstanding colors our sense of how much outrage on a platform is normal.

“There’s a lot of discussion around how to improve debates and political discourse on social media and make them less disrespectful and less toxic,” Brady explains. “One of the things this work strongly suggests is that’s not just about targeting specific users. It’s also about people’s social perceptions—because even if we could reduce the extremity, people might still perceive it.”

Overestimating outrage on Twitter

Brady teamed up with Molly Crockett and Killian McLoughlin of Princeton University, and Maria Gendron, Kara Luo, and Mark Torres of Yale University, to conduct the research. They started by looking at real Twitter users and their posts.

They used machine-learning classification to identify people who were tweeting about American politics with what the classifier determined to be either high or low levels of outrage. Then, the researchers contacted the tweet authors via direct message and asked them to report, within 15 minutes of posting, how happy or outraged they felt when they wrote a particular tweet.

Next, across several studies, the researchers had a total of 650 participants look at the tweets and rate how happy and how outraged they thought the author felt when posting. Participants also reported how often they used social media to learn about American politics.

“[People] think that outrage is normative, and that’s really important, because we know that norms are a strong predictor of group behavior.”

—

William Brady

Analyzing these data revealed a consistent mismatch: observers perceived greater outrage in the tweets than authors reported feeling when writing them. (Interestingly, participants did not overperceive authors’ happiness, suggesting that positive emotions are less easily overperceived than negative ones.) And the overperception of outrage was strongest among participants who used social media to learn about politics the most.

“We think the correlation is explained by the fact that if you spend a lot of time on social media, you’re going to form expectations about how people express themselves and how they feel,” Brady explains. “And once you form these expectations, it’s going to influence your next round of judgments when you see something that looks like outrage”—triggering a vicious cycle of expecting outrage and finding it again and again.

When outrage seems like the norm

The researchers next wanted to understand whether people might overperceive the outrage on a social media platform as a whole, not just in individual posts or their personal newsfeeds.

They used the tweets from the first experiment to create two simulated newsfeeds. The two feeds were equally matched in the levels of outrage reported by tweet authors but varied in how they were perceived by previous participants, resulting in what the researchers called a high overperception newsfeed and a low overperception newsfeed.

The researchers recruited 600 new participants and randomly assigned them to look at either the high or low overperception newsfeed. Next, participants were asked to rate from one to seven how outraged they thought members of the entire social media platform—not just that feed—were on average.

Participants who saw the high overperception feed rated the outrage on the overall platform more highly than those who saw the low overperception feed (an average of 5.82 out of seven as compared with 3.53). Additional statistical analyses revealed that participants who saw the high overperception feed relied heavily on the most-outrage-filled tweets when making evaluations of collective outrage—suggesting that particularly inflammatory posts can have an outsized influence on how users perceive the entire platform.

Another study with 1,200 new participants came to a similar conclusion. After seeing one of the same two simulated newsfeeds from the previous experiment, participants were then shown ten new tweets: five in which authors intended to convey high levels of outrage and five intended to be more neutral. Participants were asked to rate how socially appropriate these tweets would be for the platform. They also reported how politically polarized and ideologically extreme they thought users of the platform were.

Participants who saw the high-overperception newsfeed rated posts expressing high levels of outrage as more appropriate than those who saw the low-overperception newsfeed. The high-overperception participants also saw users of the platform as more polarized and more ideologically extreme, the researchers discovered.

“People view the social network as more polarized than it actually is. They think that outrage is normative, and that’s really important, because we know that norms are a strong predictor of group behavior,” Brady explains. “This suggests that when outrage is overperceived, or even overrepresented by algorithms, people might be more likely to conform to a norm of expressing outrage”—even though outrage may not really be the norm at all.

Breaking the outrage cycle

The long-term solution to excessive outrage—real and perceived—on social media may lie in changing how platforms are designed and what posts they reward. Brady also feels it’s important for everyday users to understand how those platforms work, as well as the biases and misperceptions they bring to social media.

“It’s important to increase the awareness that the things you see in your feed are not necessarily representative of your social network online, and especially offline,” he says. In some cases, people may not be as mad as you think.

Susie Allen is a freelance writer in Chicago.

Brady, William J., Killian McLoughlin, Mark Torres, Kara Luo, Maria Gendron, and Molly Crockett. 2023. “Overperception of Moral Outrage in Online Social Networks Inflates Beliefs about Intergroup Hostility.” Nature Human Behaviour.