Featured Faculty

Adjunct Lecturer in Entrepreneurship; Track Lead in the Zell Fellows Program: Entrepreneurship Through Acquisition (ETA)

Michael Meier

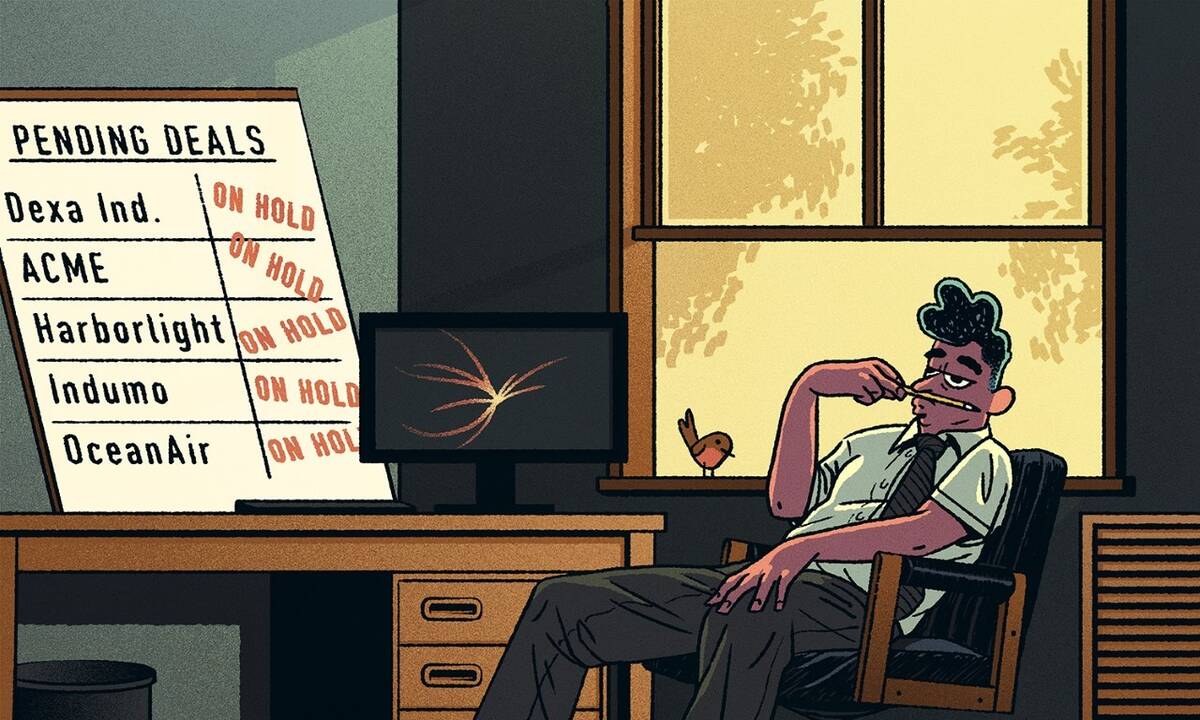

The coronavirus has caused much of the world to press a giant pause button—on social gatherings, on routine medical procedures, on sitting in classrooms.

And private equity is no exception. Deals have been halted as firms reassess the business landscape and their own finances, and concentrate on the health of their portfolio companies.

“The focus has shifted away from deal making to crisis mode,” explains Alex Schneider, cofounder of Clover Capital Partners, a private-equity firm that specializes in acquiring and investing in small businesses. He is also an adjunct lecturer of innovation and entrepreneurship at the Kellogg School. “PE firms are trying to focus on providing resources, advice, contingency planning, and liquidity to their existing businesses rather than on new opportunities.”

But the shift away from deals will be temporary, Schneider says. The pause button will be lifted.

And that will presumably happen before the economy as a whole recovers. This will present some excellent buyout opportunities for PE firms that are well positioned to capitalize on the new normal that emerges.

“Investors, by definition, are inherently optimistic,” Schneider says. “There’s optimism that there will be opportunities to invest capital that will create long-term value.”

Schneider lays out some reasons for that optimism, as well as some of the challenges that undoubtedly lie ahead.

Schneider anticipates that in the near future, PE firms—especially those with good access to capital—will resume their deal making. Deals in sectors that have remained strong during the pandemic, such as technology, and certain areas within healthcare and consumer goods, will continue on without much change. But Schneider believes other, more risk-heavy sectors like retail and entertainment will also continue to be active, but likely at lower valuations or with more deal-structure elements.

Within these areas, there will be opportunities for small-business buyouts that may not have been there a few months ago.

“This is a scary turn of events for an owner-operated small business that maybe didn’t have the capital or management resources to navigate through this,” Schneider says.

Some of those owners, who may never have considered selling or taking on a financial partner before, may be open to the idea now if it means an infusion of capital into the company or as an opportunity to diversify one’s net worth. “Once the dust settles, I think some sellers are going to be more likely to pick up the phone when PE calls,” added Schneider. “It is still a seller’s market, but the pendulum is moving in the buyer’s direction.”

“PE, with its capital and resources, will be an important part of the economy’s eventual recovery.”

Private equity will also likely be very aggressive within their existing portfolio, emphasizing strategic add-on acquisitions to capture market share and enter new channels. PE funds have strong relationships with banks and financing institutions, which will help support these synergistic acquisitions, even in difficult credit markets.

Outside of corporate finance, Schneider also expects private-equity firms to be aggressive in seeking out top talent.

“People that companies were unable to previously attract and hire are going to become available,” Schneider says. “Talented leaders will focus on joining companies that are well capitalized and positioned to grow in this environment.”

In the current market, there remain many practical challenges, even for those PE firms with plenty of capital on hand.

Despite all the spreadsheets and analysis, private equity is still a handshake industry. Maybe the next generation of dealmakers will feel comfortable making multimillion-dollar investments over video conference, Schneider says. But today, buyers and sellers need to meet in person in order to navigate the inevitable ups and downs of a deal process. Social distancing and travel restrictions, both mandated and self-imposed, are slowing down these processes and preventing deals from occurring.

Another challenge is the traditional practice of performing due diligence in person and on site.

Some parts of the process might be able to be adjusted—perhaps an accounting review can be done remotely, for instance. But anything that requires due diligence in terms of facilities, environmental compliance, or operations will be difficult if not impossible to do virtually, Schneider says.

Furthermore, debt capital is usually an important component to a private-equity deal, and most banks and financial institutions have become highly conservative in this environment. PE firms can take a long-term, equity-value-creation point of view, but lenders are focused on more near-term interest and principal payments.

“This is a really uncertain time from a lending standpoint,” Schneider says.

The near-term risk means that banks and other lending institutions will extend less credit today than they would have pre-pandemic, even off of the same historical financials. For example, an offer by a PE firm a couple months ago might have been built on the assumption that a bank would have loaned the firm 50 percent of the purchase price. But today the bank will only offer 30 percent, given all the market uncertainties.

“There’s a financing gap, and that’s a problem,” Schneider says.

Private-equity firms are adapting to this current market dynamic, Schneider says, by either renegotiating deals with sellers to include more structure in the form of earnouts and seller financing, over-equitizing deals with the expectation to refinance with cheaper debt capital when markets return to normal, or flat out lowering the purchase price. None of these strategies, especially the third, are welcomed by sellers who may choose to walk away from a deal if the valuation or terms change.

In general, Schneider has been reminded of the truth of a fundamental business lesson: cash is king.

“Companies don’t go bankrupt because of poor earnings. They go bankrupt because they run out of cash,” Schneider says. “Crises happen and it reaffirms that adage. Liquidity is the most important thing for a business to have.”

For PE firms, that means there will be a significant advantage for funds that have raised capital over the past couple years and have not yet invested it—a resource known as “dry powder”—as compared to those that deployed a lot of capital in the past few years.

“PE is something of a timing game,” Schneider says, with the advantage going to firms that are poised to start spending capital now.

(Indeed, research from Kellogg’s Filippo Mezzanotti shows that having a large reserve of cash on hand allowed PE firms to help their portfolio companies weather the Great Recession.)

And many funds likely had a fair amount of dry powder going into the crisis. A report from Bain & Co. lists 2019 dry powder reserves at $2.5 trillion.

Schneider points out that many private-equity investors were anticipating some sort of market correction, though clearly not for this reason.

“It’s been a great run, hence the ability to raise lots of capital,“ he says. “This will be a deeper and more tragic correction than anything anticipated. PE, with its capital and resources, will be an important part of the economy’s eventual recovery.”