Featured Faculty

Professor of Management and Organizations; Management and Organizations Department Chair

Lisa Röper

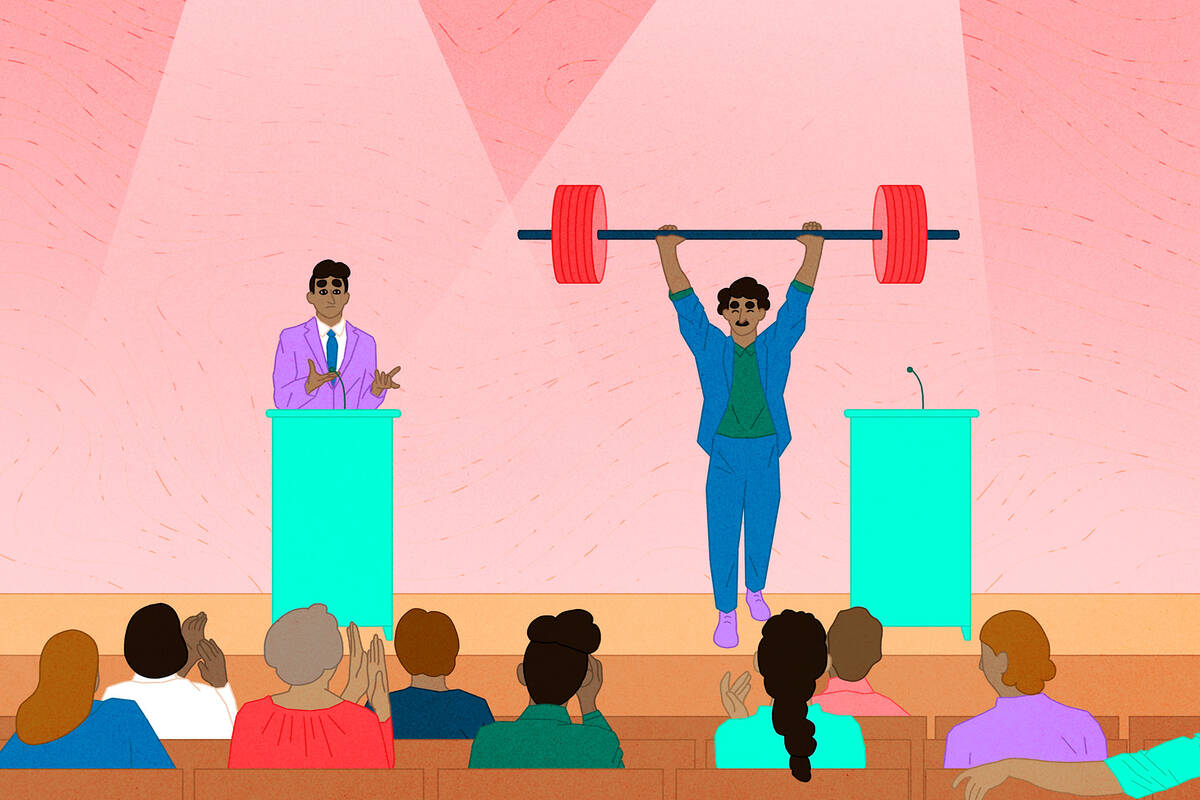

You can lead by listening carefully and building consensus. You can lead from behind or through technical expertise. You can lead with charisma. Or you can lead with iron-fisted strength and force.

For better or worse, this latter style of “strong” leadership has been increasingly popular over the last several years in realms such as politics, sports, and business.

Kellogg’s Maryam Kouchaki, along with Krishnan Nair of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and Marlon Mooijman from Rice University, investigated how people respond to this style of strong leadership in the U.S. and Europe across a wide range of races and ethnicities as well as political affiliations.

Through a series of studies based on data from 2016 through 2023, they found that ethnic minorities favor strong political leaders significantly more than do white individuals. This preference applies even across political lines: ethnic minorities who are Republican tend to have the greatest preference for strong political leaders, followed by ethnic-minority Democrats and white Republicans, with white Democrats the most averse.

“In our data, we find that white Democrats are the group that are different from all other groups, both minorities and white Republicans,” Kouchaki says.

Nair notes that these findings provide a helpful lens for understanding recent voting trends among ethnic minorities in Western democracies. It also suggests how these trends may shape the elections of political leaders in the years to come.

“Ethnic minorities are a growing proportion of the U.S. population,” says Nair, who completed a postdoc at Kellogg. “Within the next several decades, they will probably become a majority, which likely has important implications for the kinds of leaders we may elect.”

The researchers used a broad understanding of “strong leader” for their investigation: someone with a dominant and tough personality, and whose leadership style leans into undemocratic or authoritarian tendencies.

In the first of a series of studies, the researchers assessed people’s preferences for leadership style based on information from a nationally representative sample of 4,270 participants in the 2016 American National Election Studies (ANES) survey. They determined people’s attitude toward strong leadership by asking, on a 1-to-5 scale, how much participants agreed with the following statement: “Having a strong leader in government is good for the United States even if the leader bends the rules to get things done.”

[The researchers] found that, on average, ethnic minorities had much less trust in others than white respondents did and that this lower level of trust correlated with their preference for strong leaders.

In line with prior research, as well as in a replication study using the 2020 ANES survey, the researchers found that white Republicans favor strong leaders significantly more than do white Democrats.

But the team also found that, overall, Black people, Latinos, and Asians favor strong leaders even more than do white people. In fact, left-wing minorities agree that having a strong political leader is good for the country about as much as right-wing white people do—while right-wing minorities favor strong leaders even more than both of those groups.

The researchers encountered the same findings in two additional studies they conducted to determine leadership preferences: one based on the responses of American participants in the World Values Survey from 2017–2022 and another based on the responses of people from 13 different Western European countries who took part in the 2017 European Values Survey.

There is, Nair says, something surprising in these results. Polls routinely show that ethnic minorities tend to align themselves with the political left. “And yet, in spite of this, strong leaders, even those associated with the right, still have this appeal among ethnic minorities,” Nair says. “So, what’s going on?”

The answer seems to be connected to people’s level of trust.

In the same surveys about strong leaders, the researchers also asked participants a series of questions to measure their trust in other people. They found that, on average, ethnic minorities had much less trust in others than white respondents did and that this lower level of trust correlated with their preference for strong leaders.

“We believe there are two factors contributing to these low levels of trust,” Nair says. “First, a lot of minorities are recent arrivals from countries where general trust is simply lower. Second, minority groups are more likely to face a relative disadvantage, which tends to reduce people’s level of trust in others.”

The researchers conducted two experiments to further explore this relationship between trust and leadership-style preferences.

In the first experiment, people were asked to imagine they live in a fictional land called Tanjoda. Half of the participants were told that the people of Tanjoda are reliable and compassionate. The other half were told nothing about the people. Participants who were told nothing about the Tanjoda people—and were therefore less likely to trust them—were also more likely to prefer strong leaders.

The second experiment involved a game in which there was a common pool of $10. Participants were given the option to take $2 for themselves each round of the game; whatever remained at the end of the game would be tripled and distributed equally. Half of the participants heard these instructions, watched a round unfold in which none of the group members took money for themselves, and then took a survey related to strong leaders; the other half heard these instructions and then took the survey without watching a round unfold. In a parallel to the first experiment, people who did not see a cooperative round unfold were more likely to prefer strong leaders.

“We were experimentally shifting perceptions of trustworthiness, and when people believed others were more trustworthy, strong leaders were less favorable,” Nair says. “That’s not to say there aren’t other things contributing to preferences for strong leaders, but generalized trust is an important trigger.”

Nair says that their findings hold important implications for both researchers and society. For the former, it’s important to note that surveys on political opinions in the U.S. have, for decades, relied disproportionately on white Democrats, whose opinions about strong leaders are unique when compared with white Republicans and ethnic minorities.

“In our study, we show [white Democrats] to be outliers on this one specific dimension,” Nair says. “But they may be outliers in other dimensions, and that would be important to know when the samples that we’re drawing from, as researchers, are often skewed white and liberal.”

The results also speak to a contemporary political trend in democracies around the world: the rise of tough or strong leaders who may exhibit authoritarian qualities, many of whom are being propelled into office by the support of ethnic minorities. In the U.S., for example, Donald Trump’s vote share among minorities from 2020 to 2024 nearly doubled among Black voters and increased from 36 to 48 percent among Latino voters.

Whether this trend will continue to grow remains unclear, but it is likely to play a meaningful role in future elections.

“More importantly, our research indicates that these preferences extend beyond politics and are also evident within organizations,” Kouchaki says. “Recognizing and understanding these differences is essential for effective leadership.”

Dylan Walsh is a freelance writer based in Chicago.

Nair, Krishnan, Marlon Mooijman, and Maryam Kouchaki. 2025. “The Ethnic and Political Divide in the Preference for Strong Leaders.” Psychological Science.