Featured Faculty

CME Group/John F. Sandner Professor of Finance; Co-Director, Financial Institutions and Markets Research Center

Adjunct Professor of Finance; Faculty Lead of Impact Investing

Michael Meier

Sustainable finance has officially gone mainstream.

As of 2019, $30.7 trillion is held in sustainable or green funds, representing a third of all assets under management. And the share is growing quickly, with many funds reporting record flows into sustainable investment products during the first half of 2020.

“The big story in last five years is that the mainstream asset management industry has committed to getting involved in sustainable investing,” says Lloyd Kurtz, a visiting scholar at Kellogg who also leads the Social Impact Investing Team at Wells Fargo Private Bank.

Moreover, contrary to popular opinion, most investors pursue this strategy not as philanthropy, but as a logical business decision, says Dave Chen, CEO of Equilibrium Capital and adjunct professor of finance at Kellogg. “[It’s not:] ‘Hey, since you guys are out saving the world, you don’t have to generate the returns.’”

Still, confusion abounds. What does sustainable investment look like? How has it changed over the years? And what kinds of returns—social and financial—can investors actually expect to see?

We asked for the perspective of several experts, each of whom had recently served as a judge for the Moskowitz Prize, the premier global prize for research into sustainable finance, which was awarded by Kellogg for the first time in 2020.

Here’s what they had to say about the state of this rapidly evolving field.

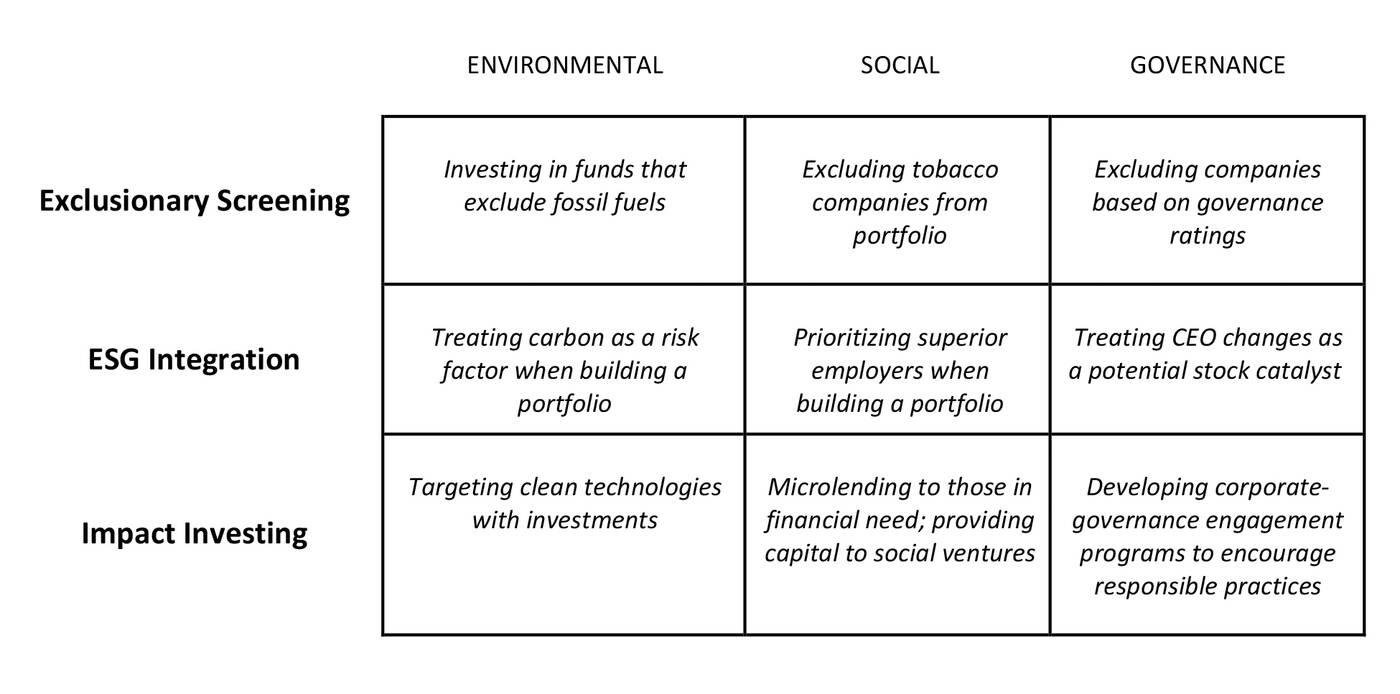

One of the reasons why sustainable investing can seem confusing is that it can take three fundamentally different forms.

The first, exclusionary screening, involves avoiding investments that go against the beliefs of the investor, explains Brian Bruce, CEO and Chief Investment Officer at Hillcrest Asset Management, and editor in chief of the Journal of Impact & ESG Investing. For example, investors (or their managers) might exclude oil, gas, and coal companies or tobacco companies when building their investment portfolio.

“While exclusionary screening has historically been associated with faith-based investment, it is the traditional method for implementing ESG strategies back to the days when the field was called ‘socially responsible investing,’” Bruce says.

ESG integration is a more recent approach that involves considering a range of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria in every investment decision.

“It goes beyond exclusions and requires assessments of ESG performance for every opportunity in the investable universe,” says Bruce. “A manager will score and assess the entire opportunity set.”

In ESG integration, managers consider criteria like how green a company or industry is, or how well it treats its employees, and then prioritize companies that score better on these assessments for inclusion in their portfolios. However, managers are generally still looking for strong financial performance from their investments.

The third technique, impact investing, starts with the slightly different aim of “promoting positive change in the world,” as Bruce describes it. While profits are welcome, they may take a back seat to other goals.

“Typical themes include clean energy, clean water, and support for education. Investors seek to achieve these goals through direct dialogue with companies (active ownership) or through specialty venture, microfinance, and/or private equity vehicles,” Bruce says.

In the chart below, Bruce provides examples of how these three different approaches might tackle various environmental, social, or governance goals.

One of the biggest questions surrounding sustainable finance is whether taking into account these ESG criteria actually benefits investors financially.

On the surface, this seems an unlikely prospect. After all, any time you place limits on the investment opportunities in your portfolio, you reduce its efficiency. Such limits—either via exclusionary screening or poor ESG performance—ought to come with financial costs, at least theoretically.

But Kurtz points out that historically this has not been the case. In fact, he says, “for many years, we’ve observed that companies with better sustainability records tend to have better earning power in terms of return on equity or return on invested capital. That’s been true almost since the start of sustainable finance decades ago.”

There are plenty of possible reasons for this. Ravi Jagannathan, a professor of finance at Kellogg, sees risk management as playing a large role in making sustainable investing profitable. In his view, professional institutional investors and money managers are obligated to maximize returns and minimize risks for their clients. That means looking ahead to how those risks might shift in the future.

“Laws are not static,” Jagannathan says. “For example, many consumers feel an ethical obligation to shift their consumption toward green products with a lower emissions footprint.” Moreover, as the public becomes increasingly aware of the costs imposed by greenhouse gas emissions, additional legislation becomes more likely. Legislators might implement carbon taxes, for instance.

“Firms with responsible business practices are better at perceiving such shifts in consumer behavior, anticipating potential changes in laws, and developing new technologies and supply chains that reduce harmful emissions,” Jagannathan says. “They are also more likely to attract and retain talented workers and have more satisfied customers—resulting in better and longer-lasting cash flows. Such firms are therefore less risky.”

In this respect, an investment manager’s decision to prioritize investing in companies that score highly on ESG criteria could simply be considered a smart part of the risk-management process. Indeed, there is some evidence this is already how some investment managers are thinking.

Similarly, large institutional investors could pressure the companies they currently invest in to make changes that would reduce risk. In fact, evidence from this year’s Moskowitz Prize–winning paper suggests that the efforts of activist investors can be quite effective. The research finds that firms targeted by activist investors went on to make capital improvements to their plants that significantly reduced the release of toxins and greenhouse gas emissions.

Chen also takes the view that investing in companies with sustainable business practices is a good financial move, particularly in industries like energy, where it’s becoming clear that a changing climate will change demand moving forward.

For many investors and investment managers, he says, the decision process is quite simple. “We’ve recently hit an inflection where investors have to ask themselves: ‘Do I want to invest in yesterday, or am I investing in the growth industries of tomorrow?’”

Tesla is being handsomely rewarded by the market, after all, because it believes that the low-carbon, electric economy will ultimately become the transportation economy of the next few decades.

“The investors that are skyrocketing this asset are not doing it because they believe that sustainable investing is a ‘gimme’” or act of charity, Chen says. Indeed, when GM announced its pledge to sell only zero-emissions models by 2035, its stock jumped 3.5 percent by the end of the day.

“We’ve recently hit an inflection where investors have to ask themselves: ‘Do I want to invest in yesterday, or am I investing in the growth industries of tomorrow?’”

— Dave Chen

Ditto for investments into, say, high-production greenhouses. Chen’s firm manages funds that invest in greenhouses that create a controlled environment, managing the carbon dioxide, temperature, light, and humidity levels to optimize vegetable productivity, safety, and quality.

“Seventy percent of what we eat comes out of California, because California has perfect weather,” he says. “But the weather in California is changing: climate issues, drought issues, fire issues.”

“Effectively, every day is the same in this greenhouse and every day is tuned to the spectrum of light and the climate characteristics that a specific plant thrives in,” Chen says. “This becomes a climate adaptation tool and a tech-enabled productivity tool. Am I investing because this a ‘gimme’ or because this is the future? Investing in the next generation of the economy is just a smart investment.”

Whatever the reason, investors have taken note. Demand for sustainable investing, particularly from institutions, has never been larger.

“It is no longer a niche product. It is considered an essential part of the asset-management industry. And the reason for that is that customers are demanding it,” says Kurtz.

But he notes that as interest in the field has blossomed, so has scrutiny.

“Over the past decade, there’s been a significant increase in the staffing of ratings agencies, and in the professionalization and implementation of the ratings systems,” Kurtz says. “So when we say a company is a ‘good sustainability performer’ or ‘bad sustainability performer,’ there’s a lot more detail and nuance that’s going into that judgment.”

Different ratings agencies will prioritize different criteria—and likely come to different conclusions about how a given company fares. This complexity, he explains, will make it increasingly difficult to draw a simple, tight relationship between sustainability and financial returns. Instead, he predicts that we will start to learn that some sustainability efforts produce more financial gains than others, and that effectiveness could differ by industry.

Having more granular information will be critical for helping both investors and companies make socially and financially smart decisions. For instance, says Kurtz, “two very strong studies by Alex Edmans at London Business School documented a relationship between the way companies treat their people and the financial results they got.”

And research from Kellogg’s own Aaron Yoon supports the importance of employee satisfaction, finding that having satisfied employees is a necessary condition for seeing a financial boost from other kinds of ESG investments.

It is also important to understand that investors who take the third approach toward sustainable investing—impact investing—may see lower financial returns. “As you move away from public markets and toward products designed with a philanthropic component—such as community foundations or microfinance lending—you’re entering an intermediate space between an investment and a grant. And so there it’s perfectly appropriate to expect that the returns won’t be market returns,” says Kurtz.

Still, impact investors interested in getting the biggest bang for their buck will want to stay tuned: future research should also illuminate the efficiency of various tools for achieving social goals.