Featured Faculty

Glen Vasel Professor of Finance; Director of the Heizer Center for Private Equity and Venture Capital

Lisa Röper

Market efficiency is one of the most widely taught concepts in finance, one of the most powerful ideas in finance, and also one of the most misunderstood ideas in finance. Let’s start with a simple definition: Markets are “efficient” when the price of a security is equal to its value. If markets are efficient, purchasing and selling securities is a zero net present-value investment: You pay $100 in cash for something worth $100.

Market efficiency arises from investors’ mercenary interest in making money. Some investors spend time and money to research the value of stocks. This is costly, and some people are better at it than others. When these investors find stocks that are cheap (their price is less than their value), they buy and in the process push the price of the stock up toward its value. When they find stocks that are expensive (their price is more than their value), they sell and in the process push the price of the stock down toward its value. They don’t care about making prices right. They care about making money.

When I first started teaching, there was a lot of resistance to the ideas embedded in the efficient market hypothesis. Students and practitioners would ask: Do you really believe that the price of every security is always equal to its value? If so, how do you explain the presence and size of the active money-management industry?

These are reasonable questions and point out that the efficient market hypothesis is just a theory, albeit one that has been incredibly influential on the practice of finance. The research required to figure out which stocks are cheap or expensive is costly, and avoiding these costs by investing passively can raise investors’ returns. As the Wall Street Journal’s Jason Zweig has pointed out, “The machines that run index funds cut the costs of investing by 90% or more by skipping most of the research and trading their human rivals engage in.” Financial economist Kenneth French finds that “the typical investor would increase his average annual return by 67 basis points over the 1980–2006 period if he switched to a passive market portfolio.”

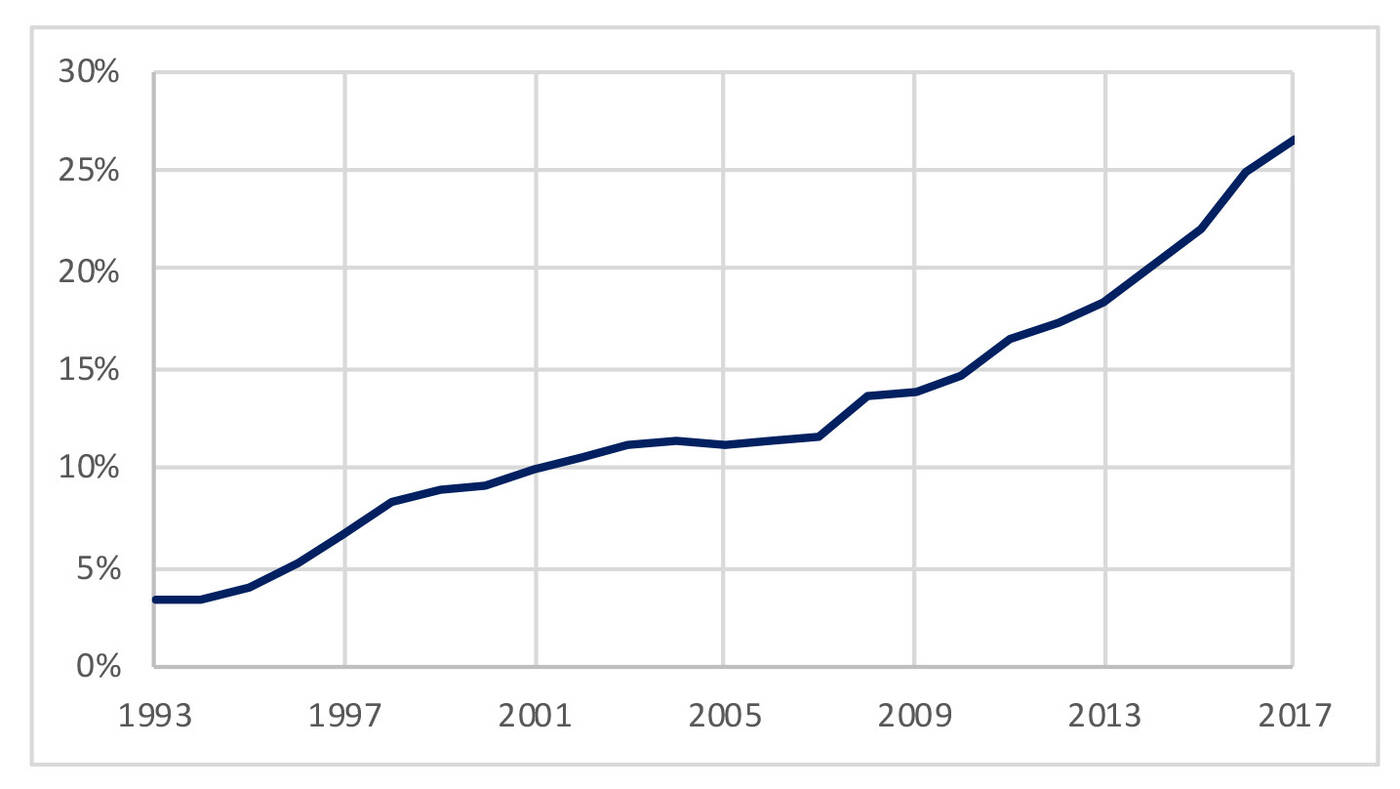

If it were true that prices are always correct, then research into the value of securities would be a bad investment. In this idealized world there are no cheap or expensive stocks. This observation, combined with the costs of active investing and its mixed record on average, has led to a dramatic growth in passive investing. The fraction of money invested in index funds, as opposed to active equity mutual funds, has risen from 3 percent in 1993 to 27 percent in 2017.

Theories are useful logical constructs that help us understand how the world works. They are not meant to be a complete description of reality, which raises the question of what real world frictions are missing from the theory. The efficient market hypothesis does not assume that the price of a security equals its value; it concludes this. This conclusion follows from other underlying assumptions. So which cosmic forces are making markets efficient? The active investors who spend their time and money researching the value of stocks and uncovering which ones are cheap or expensive. The moment that everyone agrees that markets are efficient, then investing in research is a waste of time and money. In this world, no one should invest in research. However, if no one is doing the research, which forces cause prices to converge to their value?

This brings me to the Groucho Marx Theory of Efficient Markets: “Markets are efficient only so long as a sufficient number of people believe that they are not.” My title is, of course, based on the quote from comedian Groucho Marx, who said, “I don’t want to belong to any club that would accept me as one of its members.” There are some theories that are true because people believe them—we call them self-fulfilling prophecies. This is a theory that can only be true so long as not everyone believes it and acts on that belief.

For capital markets to be efficient, or more accurately, for them to move in the direction of efficiency, there has to be a sufficient number of investors who do not believe prices equal value.

— Mitchell Petersen

For capital markets to be efficient, or more accurately, for them to move in the direction of efficiency, there has to be a sufficient number of investors who do not believe prices equal value. These active investors who spend their capital and their presumably expensive time researching stocks are the reason that others can believe that markets are efficient. These active investors figure out which securities are cheap (in ways the market does not see) and which ones are expensive (in ways the market does not see). This is the internal inconsistency of the efficient market hypothesis: it works as long as enough investors believe it does not.

At what point does this balance of believers and nonbelievers break down? Or said another way, when does passive investing become too large? This is an empirical question.

More importantly, it is a problem that should be self-correcting. If the active sector becomes too small, and no one is putting in the time and effort into keeping prices efficient, then the price of stocks may wander away from their value. If markets become wildly inefficient, and prices stray far from value, then the return to figuring this out gets big. It is now profitable for active investors to spend money on research and find mispriced stocks to buy or sell. If they are correct, and if they have a competitive advantage in finding mispriced stocks, they will outperform a passive benchmark. The incentive to maximize expected returns after transaction costs will constantly adjust how many resources are allocated to active investing and thus return markets to a path of continually approaching efficiency.

Understanding that market efficiency is a journey, not a destination, also highlights the social value of capital markets and active investors. Capital is costly. As a society, we would like capital allocated to the highest value investments. Passive investors do not research investments and do not set prices. They free ride off the prices set by active investors. They are able to buy and sell stock at the right price because the active investors have pushed prices to their correct value. It is the mercenary actions of active investors that provide the social good of more accurately pricing an economy’s assets. And if active investors do better than average (earn positive risk-adjusted returns), those who trade against them will lose.

Editor’s note: Feedback on earlier draft from Beverly Clingan, Kent Daniel, Marc Katz, and Mark Scovic is gratefully appreciated.